Untitled Document

June 6, 2005

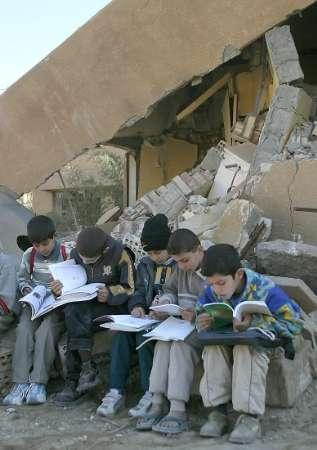

Six months after the U.S. war on Falluja, many residents still live in refugee

camps and students attend classes in tents.

Many school buildings, like almost everything else in the city, are heaps of

ruin. They are without walls, doors or windows – the outcome of U.S. bombardment

and aggression.

It is still hard to enter the city, as visitors must pass through U.S. checkpoints

that utilize high-tech equipment to try and scrutinize anyone entering or leaving.

I was standing in a long queue at the al-Jisir Entrance. Many students were

waiting to enter the city. “Everyday we wait here for at least one hour.

The city is under a curfew which ends at 8:00 a.m. U.S. troops are not nice.

They try to humiliate us,” said Kahlil al-Talib, a high school student.

Another, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said U.S. troops subject everyone

to “intensive scrutiny” before allowing people to pass. “We

are insulted and humiliated by them (U.S. troops). You can be checked several

times before entering the city,” he said.

Thousands of students in the nearby towns and villages attend high school in

the city. “There is no high school in our town, and Falluja is the closest

to us. Still, I must walk 4 kilometers to reach the checkpoint, where I am made

to wait for over an hour. By the time I reach the new tent school, classes have

already started,” he added.

Kareem Abdulhussein, head of the city’s teachers union, denied reports

that the city was being rebuilt with U.S. money. “There are no serious

efforts taking place to reconstruct the city and its schools. Contractors receive

huge amounts of money but nothing is done,” he said.

Once inside the city, I traveled to the al-Shuhada district, the scene of some

of the most ferocious fighting in the November 2004 U.S. onslaught. The schools

in this area were all destroyed. I asked what had happened to the students,

and a resident pointed to a partially damaged mosque nearby, where scores of

tents were pitched.

“Our school was leveled. We use a room in the mosque for administration

and have classes in tents,” said Ibrahim Sarhan, the principal of the

al-Bab School.

Karima Hassan said she tries her best to conduct classes inside the mosque

for her all-girl Mafakhir School. The school was also destroyed.

I then headed to Hay al-Julan where I saw two more destroyed school buildings.

In the northern part of the city, there was less destruction. Residents said

that the fighting in the area was “less severe” than in other quarters,

but still the school buildings there had sustained heavy damage.

It is not clear why the city’s schools have borne the brunt of such overwhelming

damage. I counted 65 school buildings that were heavily damaged or completely

destroyed.

Falluja is still a ghost town because little has been done to undo the damage

inflicted by U.S. forces. Officials say of the 30,000 homes that were damaged

and nearly 5,000 that were completely destroyed; only a few have been repaired.

In addition, very little has been done to repair the 8,500 businesses, 60 mosques

and 20 government offices that were damaged.

“The situation is extremely bad,” said Abdulla Saleh, a senior

education official in the city.

He said that the few schools that survived the fighting were still occupied

by either U.S. or Iraqi forces.