Untitled Document

At the request of Judicial Watch, the US Department of Defence released

the full version of the September 11th, 2001 attacks on Pentagon security camera

videos. The neo-conservative press is delighted at this broadcasting, which

supposedly contradicts conclusively our analyses. In fact, the video does not

contain any additional element in comparison with the images already broadcast

in 2002, and where it is still impossible to see a Boeing 757-200. This sequence

confirms, on the contrary, the analysis of the former artillery officer Pierre

- Henri Bunel published by Thierry Meyssan in his book Pentagate, and that we

reprint here today.

Videos released on May, 16th 2006 by the United States Department of

Defense

Judicial Watch

September 11 Pentagon Video -- 1 of 2

Judicial Watch

September 11 Pentagon Video -- 2 of 2

The Effects Of A Hollow Charge, 4th chapter of book

Pentagate

What is the nature of the explosion that took place at the Pentagon on 11 September

2001? An an’alysis of the video pictures of the impact and the photographs

of the damages permits one to know by what type of device the attack was caused.

Did the explosion correspond with that produced by an airplane’s kerosene

or that of a real explosive? Did the fire correspond with a hydrocarbon fire

or with a classic blaze?

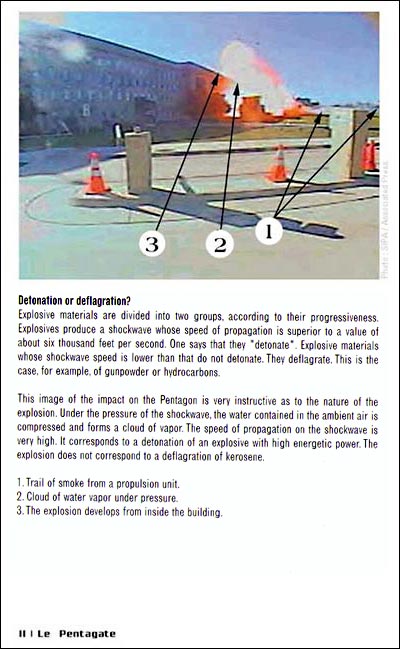

Deflagration or detonation?

As a preamble, it seems indispensable to make clear to the reader an essential

distinction: the difference between a deflagration and a detonation.

The combustion of explosive chemical materials - powders, explosives or hydrocarbons,

for example - release energy by producing a shock wave. The diffusion at high

speeds of the enormous quantity of gas produced by the chemical reaction is

accompanied by flame, by a noise caused by the displacement of the shockwave

through the air, and by smoke. One also often observes, even before seeing the

flame, a cloud of vapor due to the compression of the air surrounding the zone

of the explosion. The air can’t be set into motion immediately, so it

compresses under the influence of the shockwave. At first, under the compression

of the air molecules, the invisible water vapor that the atmosphere always contains

in greater or lesser quantities compresses and becomes visible as a white cloud.

What I would like to underline here is the notion of the shockwave. An explosion

is a reaction that projects gas at a greater or lesser speeds. Explosive materials,

according to their chemical composition and the physical arrangement of their

molecules, impart upon the gases they generate a greater or lesser speed of

propagation. One says that they are more or less progressive. The observation

of the shockwave is thus a precious indication of the speed of the gases projected

by the explosion.

Explosive materials are divided into two groups, according to their progressiveness.

Explosives produce a shockwave whose speed of propagation is superior to a value

of about six thousand feet per second. One says that they "detonate".

Explosive materials whose shockwave speed is lower than that do not detonate.

They deflagrate. This is the case, for example, of gunpowder or hydrocarbons.

In an internal combustion engine - and the turbojet of a Boeing 757 is a continuous

internal combustion engine - the fuel under pressure deflagrates and does not

detonate. If it detonated, the engine’s structure would not withstand

it. The kerosene of an airliner that crashes ignites and does not generally

produce even deflagration, except in certain circumstances and at points limited

to the engines. In the recent case of the Airbus that fell on a Queens neighborhood

in New York in November 2001, the engines did not explode upon arriving at the

ground. Kerosene is a heavy oil analogous to diesel fuel, tri-filtrated in order

to satisfy the physical conditions of passage through the fuel injectors of

jet engines. It is in no sense an explosive.

The color of explosions as also fairly remarkable. In detonations, the shockwave

displaces itself rapidly. If the explosion occurs in the air without obstacles,

the flame is often pale yellow at the point of the explosion. As it moves away

from ground zero it turns orange then red. When it encounters obstacles, such

as the walls of a building, one practically doesn’t see the pale yellow

part. The duration of illumination by this color is brief. The form of the flame

gives an impression of "rigidity" because of the speed of propagation.

It is only when the dust lifted by the shockwave starts to bum due to the brutal

rise in temperature that smoke appears. This is fire smoke that has little resemblance

to the black, heavy coils given off by hydrocarbon fires.

But solid explosives are not simply chemical combinations. One can improve

their effectiveness by playing with their physical forms. In principle, the

shockwave propagates perpendicularly to the surface undergoing reaction. By

working the shapes of the explosive charges one can orient the shockwave in

such a fashion as to send a maximum of energy in a given direction, like directing

the light of a lighthouse with a reflector. We thus find spherical charges whose

shockwaves go in all directions; cylindrical charges like those that equip shrapnel

shells, those weapons that burst into minuscule pieces of steel the size of

a tab of chocolate and spray the battlefield; t1at charges, that allow making

holes in plane obstacles with a minimum of energy lost in useless directions;

but also hollow charges. These latter concentrate the principal shockwave in

the shape of a high-temperature jet bearing a quantity of energy capable of

piercing armor made of steel, composites or concrete.

The ignition

The explosive that constitutes the weapon [1 ] should explode

at the desired time. In order for it to react exactly as the user wishes, it

needs a certain degree of stability. The explosive that constitutes the principal

charge of a weapon is too stable to explode by a simple shock. In fact, to initialize

the chemical reaction, the charge must be submitted to a shockwave provoked

by a more sensitive and less powerful explosive that we call the detonator.

The explosive charge of the detonator reacts to a shock, to a spark or to an

electrical or electromagnetic impulse. It then creates a shock wave that provokes

the detonation of the principal charge.

The system that commands the explosion of the detonator is called the ignition

system. The devices vary considerably and it would take too long to examine

all of them. I will thus only deal with the two systems that might have been

used at the Pentagon, explosive ignition systems commanded by the operator and

ignition systems for hollow charges by instantaneous percussion with a short

delay.

Shells, bombs or missiles are equipped with an ignition system which comprises

the release, the delay system and a detonator. This device is called a fuse.

It is fixed on the weapon either during its construction, or at the moment of

conditioning for firing. It includes a security system that prevents the ensemble

from functioning until being armed.

The release can be activated by a shock in the case of percussion fuses, by

a radar detector at a distance in the case of radio-electric fuses, by the reaction

to a source of heat or a magnetic mass in the case of thermal or magnetic fuses.

Either the release provokes detonation instantaneously, or the delay system

acts so that the weapon only detonates several milliseconds after the impact.

In this last case, the weapon begins to penetrate the objective by physically

denting it with its armor. The charge detonates once the weapon has already

entered the objective, which increases its destructive effect.

For certain very hard fortifications, one even finds that there are multi-charge

weapons. The first charges fracture the concrete, while the later one or ones

penetrate and detonate. In general, anti-concrete charges are hollow charges.

The jet of energy and melted materials penetrate the fortification and spread

inside quantities of hot materials pushed by a column of energy that pierces

the walls like a punch. The great heat produced by the detonation of the hollow

charge provokes fires in everything that is combustible inside.

During the Gulf War, the anti-fortification missiles and guided bombs pierced

all of the concrete bunkers that were hit, notably at Fort As Salman. A single

bomb could pierce through three thicknesses of armored concrete, having begun

with the thickest, on the outside.

The missile

In order to conduct an attack with such a weapon system, a launcher is obviously

needed. In the case of guided bombs, the launcher is a plane or at the very

least a powerful helicopter. The weapon then leaves with an initial speed which

is that of the carrier vehicle. It descends in a glide and generally guides

itself by following a laser illumination. In the case of a missile, its range

is much greater because the missile has its own engine. If needs be, one can

conceive a system so that the missile depart from its own launch pad on the

ground. There are in fact ground-to-ground anti-fortifications missiles.

A cruise missile of a recent model generally follows three phases of flight.

The launch, during which it attains its tlight speed in emerging from the bay

of an airplane or a missile launch-tube. Pushed forward by the engine at full

power, it reaches its cruising speed and deploys its wings and tail fins. It

then descends to its cruising altitude and follows its approach trajectory.

In the course of this flight phase, it frequently changes direction, turning

according to the Hight program, climbing or descending to remain low enough

to escape detection as far as possible. One might then mistake it for a fighter

plane in tactical Hight maneuvers. It keeps this altitude until it reaches the

point of entry to the terminal phase. This point is situated a certain distance

from the objective; two or three miles depending on the models. From this point,

the missile flies in a straight line t?wards the target and undergoes a strong

acceleration that gives it maximum speed to strike the objective with the maximum

of penetrative force.

The missile thus has to reach the point of entry to the terminal phase with

great precision, so that before acceleration it is not only in the right spot

but also pointing in the right direction. That is why it often happens that

the missile ends its cruising flight with a tight turn that allows to adopt

the right alignment. A witness might observe that the missile reduces its engine

power before throttling back up.

The type of explosion observed at the Pentagon

On 8 March 2002, a month after the beginning of the controversy on Internet

and three days before The Big Lie was published in France, five new images of

the attack were released by CNN [2 ]. A photo agency then distributed

them very widely to numerous newspapers throughout the world. These images originating

from a surveillance camera were not made public by the Pentagon itself, which

contented itself with authenticating them. In them, one can see the flame developing

from the impact on the façade of the Department of Defense’s building.

The first shot (Photo Section, p. II) is that of a white puff that seems to

be a white smoke. It definitely calls to mind the vaporization of the water

contained in the ambient air at the beginning of the deployment in the atmosphere

of a supersonic shockwave of detonating material. One distinguishes, however,

traces of red name characteristic of the high temperatures reached by the air

under the pressure of a rapid shockwave.

What is plain to see is that the shock wave starts from the interior of the

building. One sees above the roof the emergence of a ball of energy that isn’t

yet a ball nf fire. One might legitimately think of a detonation by an explosive

with a high energetic power, but for the moment it still cannot be determined

whether it is a charge with a directed effect or not.

One distinguishes at ground level, starting from the right-hand side of the

photo and going to the base of the mass of white vapor, a white line of smoke.

It looks very much like the smoke that leaves the nozzle of the propulsion unit

in a flying vehicle. As opposed to the smoke that would come out of two kerosene-fueled

engines, this smoke is white. The turbojets of a Boeing 757 would in fact leave

a trail of much blacker smoke. The examination of this photo alone already suggests

a singleengine flying vehicle much smaller in size than an airliner. And without

two General Electric turbopropulsion units.

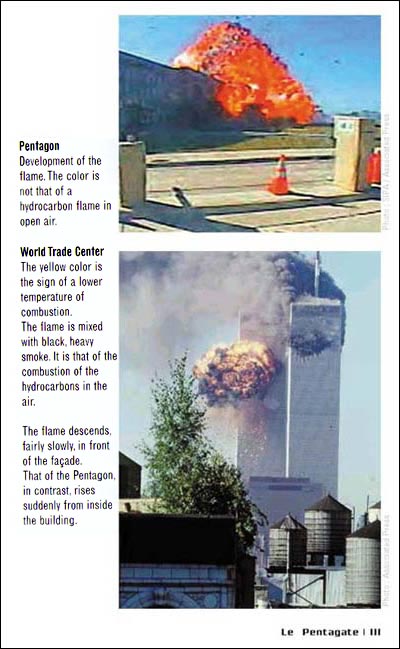

In the second shot (Photo Section, p. III) one still sees the horizontal trail

of smoke but one can also make out very clearly the development of the red flame.

It is interesting to compare this shot of the impact at the Pentagon with that

of the impact of the plane with the second tower at the World Trade Center (Photo

Section, p. 1II). The color of the latter is yellow, which points a lower temperature

of combustion. It is mixed with black, heavy smoke. It is the color of hydrocarbon

combustion in the air. In this case, it is kerosene contained in the airplane

that is burning. This flame descends quite slowly down the front of the fa,ade

where the plane had penetrated, carried by the falling fuel. In contrast, the

flame of the Pentagon explosion rises sharply from inside the building, ripping

off debris that one sees mixed with the red flame. There is no longer the cloud

of vapor due to the shockwave that masked the flame in the first photo. The intense

heat has caused it to evaporate. As we have seen, that is characteristic of detonations

of a high-yield explosive.

We should take the opportunity here to note the appearance of the smoke rising

from the first tower that was hit, as the fire develops there. It consists of

heavy, oily coils. As for traces in the air of the airplane, as opposed to the

aircraft that seems to have hit the Pentagon. there is no trail although the

impact has just taken place.

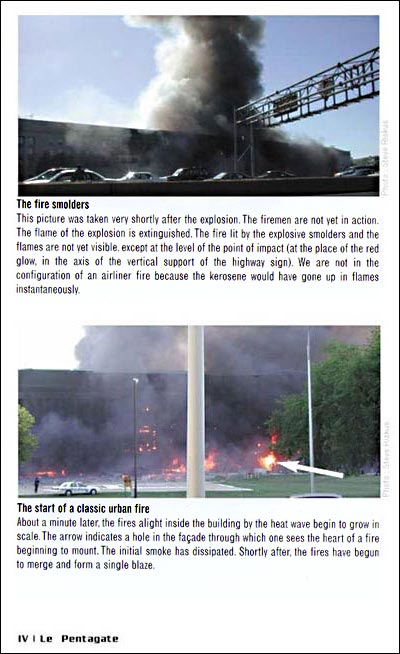

The photos on page IV of the color section were taken a short time after the explosion.

The firemen are not yet in action. In the one at the top, the flame of the explosion

itself has extinguished. The fire llt by the explosion smolders and its flames

are not yet visible, except at the level of the point of impact, where one perceives

a red glow in the axis of the vertical support of the highway signs. We are thus

not seeing the configuration of an airliner fire because the kerosene would have

ignited instantaneously. The fa,ade has not yet collapsed. It does not present

any visible signs of major mechanical destruction, although the upper floors and

the roof have already been hit by the blast.

In the photo below, taken according to its author about a minute later, the

fires ignited inside the building by the heat wave have begun to spread. The

arrow indicates a hole in the fayade through which one sees the heart of a fire

beginning to mount. The façade still has not collapsed and the initial

smoke has dissipated. It is only after the fires have begun to merge and fom

a single blaze that the thickest smoke appears, but without presenting the same

appearance as the smoke from an airliner fire with its reservoirs of kerosene.

To sum up, the examination alone of these photos that everyone has seen in

the press permit one to measure the striking differences between the two explosions.

If the flame of the World Trade Center is obviously that of kerosene from an

airplane, it would seem that this is not at all the case at the Pentagon. The

flying device that struck the Department of Defense has, at first sight, nothing

to do with the airliner of the official version. But we have to continue the

investigation in order to progress in our search for elements that will perhaps

permit us to determine the nature of the explosion that damaged the Pentagon.

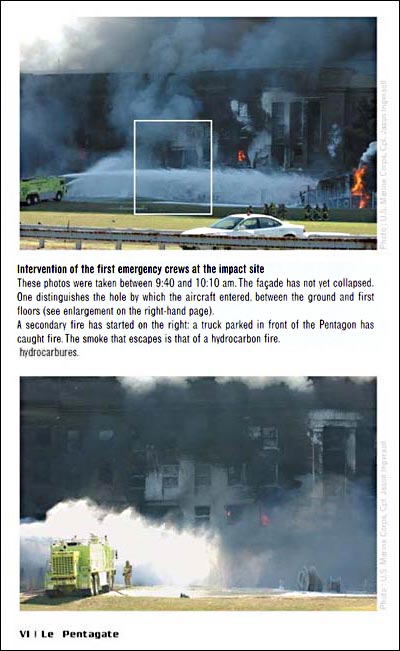

A hydrocarbon fire?

When the firemen intervened on the site, one sees clearly that they are using

water to attack the fire (Photo Section, p. X). Several official photographs

show a fire truck that we in France would call a CCFM (carnian citerne pour

feu moyen - a tanker truck for a medium-sized fire). The water coming out of

the hoses is white in color, so it does not contain that substance used on certain

fires known as a "retardant". In general, retardants give the water

a reddish or brownish color. Thus the principal fire being attacked is not a

hydrocarbon fire, because one cannot see any foam cannons that are characteristic

of interventions in airplane accidents or any hoses projecting adapted products.

However, the examination of the photo at the top of page VI does show the residues

of carbonic foam, The explanation is given in certain accounts of September 11

according to which either a helicopter, for some, or a truck, for others, parked

close to the fayade, exploded. One can see in any case on many pictures a truck

on fire to the right of the impact. On the other hand, the quantity of foam residues

is relatively small. Essentially, it is spread not on the building fire but on

the lawn that stretches in front, as if they had extinguished a fire set alight

by that of the attack. This is what is known as a "sympathetic fire",

in French firemen’s jargon. A foam hose was thus used to put out one or

more secondary fires.

One can see in the pictures released by the Department of Defense a truck armed

with a foam cannon attacking a fire situated in front of the façade,

while the high-powered water pumps attack the main fire inside the building.

The spraying as it is being carried out at that moment manifestly aims at lowering

the general temperature by wetting everything first, before penetrating into

the building to extinguish fires point by point.

Artillery, intelligence and BDA

After having given my reactions as a fonner firefighter, I’m now going

to give those of an artillery officer and observer. Among his tasks, an artillery

observer must pick out objectives, estimate the type of weapon needed to be

deployed to treat them and the quantity of projectiles required to render them

harmless. Once the objective has been treated, one must still evaluate the real

damage to measure whether the first strike was sufficient or if firings should

continue.

It’s a matter of establishing an appraisal of the damages that is then

transmitted to the command and intelligence echelons. This evaluation of battlefield

damages is called in English a Battlefield Damage Assessment (BDA). One must,

of course, employ maximum objectivity in these evaluations: it would be stupid

to ask for more firings on an objective that had already been neutralized or

destroyed, but just as stupid to let it be thought that an objective had been

rendered harmless when it still presented a menace.

During the Gulf War, every day there was a meeting in General Schwartzkopf’s

command post between tq..e French, British and American commanders-in-chief.

A part of the "intelligence" chapter of this briefing dealt with the

examination of BDA photos. And Schwartzkopf paid particular attention to this.

In these pictures one saw the effects of weapons and the scale of damage inflicted

on the objectives.

This was not mere voyeurism on the part of the three generals. It permitted

them to decide if there was reason to continue attacking objectives already

treated, but also to decide whether to use less powerful weapons in order to

prevent the destruction inflicted on military objectives from impinging on the

civilian environment. Needless to say, for the interpreters of images, artillery

observers and intelligence officers, damage evaluation was a key matter that

we studied carefully. And when one adds practical experience to theory, as unfortunately

was my case, one does possess some elements of objective appraisal in examining

the damage suffered by a building; especially if one knows the building well,

as is also true in my case concerning the Pentagon.

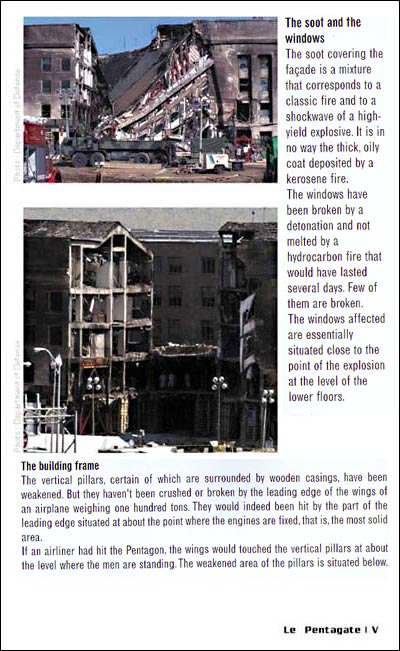

The official photos of the facade

A general view of the façade is highly interesting. Furnished again

by official bodies, it is presented at the top of page V of the Photo Section.

As the firefighters finished working on the exterior of the building, one can

make out several instructive elements. First of all, the soot covering the fayade

is a mix of that which would have been deposited in a classic fire and others

more characteristic of those deposited by the shockwave of a high-yield explosive,

but in no way of the thick, oily coat deposited by a kerosene fire. The windows

have been broken by a detonation and not melted by a hydrocarbon fire that would

have lasted several days. The most remarkable thing is that relatively few of

them are broken, and that the windows affected are essentially situated close

to the point of the explosion at the level of the lower floors. Near ground

zero, therefore. It is very likely that the shockwave was propagated along the

corridors, and one follows it very well in the general overview shown on page

XI of the Photo Section. This corroborates the testimony of David Theal1 [3

]. This liaison officer at the Pentagon describes the sudden arrival of a violent

noise accompanied by debris that ravaged the corridor outside his office.

At the beginning of its displacement, the shockwave broke panes and, once it

was channeled by the walls of the corridors, it took an orientation that no

longer had as much effect on the windows. It should be made clear that these

were double-glazed windows in which the outer pane is particularly solid. That

was what a representative of the company that installed them declared [4

], and it’s also what was explained to me well before this attack, during

an official visit to the Pentagon as an observer.

On a picture that is a more detailed close-up, at the bottom of page V, one

has a view of the impact zone after wreckage was cleared. It allows one to make

out the vertical concrete pillars of the building’s frame and the corridors

that fun along the floors. One understands better then how the shockwave bypassed

the windows as we mentioned above.

The shot shows that the vertical pillars, some of which are surrounded by wooden

casings, have obviously been weakened at the ground level, that is, the place

where the detonation occurred. But they weren’t crushed or broken as would

have been the case if they were struck by the leading edges of the wings of

a hundred ton airplane. They would have been hit by the part of the leading

edge situated approximately at the spot where the engine pods are fixed, the

most solid area. Manifestly, no wing has struck these vertical pillars of the

building’s concrete frame.

If a plane had struck the Pentagon, as the official version would have us believe,

the wings would have touched the vertical pillars at approximately the level

of the floor on which one can see men standing. It’s obvious that the

weakened zone of the pillars is located below, where one can see the wooden

casings and the red-colored steel props. So the vehicle that carried the charge

that weakened the pillars struck lower than an enormous airliner would have

done. And r refer you back to the first photographs studied on which we could

see the trail of smoke from a propulsion unit very close to the ground.

This picture also permits us to put into context statements by certain experts,

according to whom "the Pentagon is constructed of particularly solid materials".

It’s true that the building’s contractors used hardened materials

for the windows and the outer facings, but the Pentagon is no more a blockhaus

than an armor-plated car is a tank.

An anti-concrete hollow charge

The last photo was produced by the Department of Defense and published on

a Navy Web site [5 ]. It is presented on page XII of our Photo

Section. In examining it, one can see an almost circular hole topped by a black

smudge, This perforation is about seven feet in diameter and is situated in

the wall of the third line of buildings working inward from the façade.

It is supposed to have been made by the nose of the plane.

That would mean that the nose of the aircraft, a radome of carbon fiber that

is far from being armored, would have traversed without destroying them six

load-bearing walls of building considered to be rather solid. And what would

then be the cause of the black smudge marking the wall above the hole? The hydrocarbon

fire. But then, all of the façade of this building would be marked with

soot and not only the few square feet that have been really blackened. And the

broken windows, was that the result of the impact? I remind you that the windows

are solid.

The appearance of the perforation in the wall certainly resembles the effects

of anti-concrete hol low charges that I have been able to observe on a number

of battlefields.

These weapons are characterized by their "jet". This jet is a mixture

of gas and melted materials that is projected in the direction of the axis of

the paraboloid that constitutes the forward face of the weapon. Propelled at

a speed of several thousand feet per second, with a temperature of several thousands

of degrees, this jet pierces concrete through many feet of thickness. It could

thus pierce five thick walls of the building without any problem. Five walls

out of six because the fayade was perforated by the vector itself. The detonation

of the military charge only occurs, in fact, once it has been carried inside

the objective. As I eXplained earlier, the fuses arming anti-concrete charges

are not instantaneous, but have a short delay. That is why the flame of the

explosion developed from within, the interior of the building towards the exterior.

As one sees on the photos taken by the security camera, the shockwave damaged

the fa,ade, the upper floors and the roof, and propagated itself through the

corridors at the height where the vector had struck: on the ground level.

The jet contains gases at a high temperature that slow and finally come to

a halt before the melted materials. The gases burn everything combustible in

their path. A schematic diagram of the flame and the jet of a hollow charge

that is piercing walls is shown on page XIII of the Photo Section.

The melted materials travel further than the gases, and in this particular

case, the picture of the last hole certainly resembles the effect that the melted

materials of a jet would have had at the end of their trajectory. They would

have been finally stopped by the last wall they reached. But still fairly hot

enough, they would have marked the wall with this black smudge, just above the

hole. Heat rises from materials that are beginning to cool and thus only mark

the fayade above the impact. At this terminal point, the temperature is no longer

high enough to make more of a mark on the cement. On the other hand, the remnants

of the shockwave still have enough energy to break the windows immediately around

the hole. One understands then why the firefighters intervened with water. It

is the extinguishing t1uid with the strongest heat-to-mass ratio. It is thus

the best -adapted to cooling materials that have absorbed a "heat wave"

and to extinguish fires in urban areas that have been lit by sympathy. It was

not a matter of the firefighters extinguishing a hydrocarbon fire, but of putting

out punctual fires and cooling overheated materials.

This photo, and the effects described in the official version, lead me therefore

to think that the detonation that struck the building was that of a high-powered

hollow charge used to destroy hardened buildings and carried by an aerial vehicle,

a missile.

Pierre-Henri Bunel is a graduate of the Ecole Militaire

de Saint-Cyr (the French officers’ academy) and a former artillery officer,

whose expertise is recognized in the following fields: the effects of explosives

on humans and buildings, the effects of anillery weapons on personnel and buildings,

firefighting for specific types of fire, wrecks and remains of destroyed airplanes.

He participated notably in the Gulf War, at the side of Generals Schwartzkopf

and Roquejoffre.

This author's

articles

Pentagate is fully accessible in both PDF and HTML formats,

free of charge, on the website Pentagate.info

.

Pentagate is also available in the Voltaire

Network online bookshop .

______________________

[1 ] In military language, the ammunition is the ensemble

of the propulsive charge and the projectile. The weapon is the launcher for

small caliber launchers. and the projectile itself for large caliber weapons

systems. Thus the weapon of an artillery man is the sllell or the missile, not

the cannon or the launch pad.

[2 ] ’Images show September II Pentagon crash’,

CNN, R March 2002 (report includes video clip of explosion): http://www.cnn.com/2002/US/03/07/gen.pentagon.pictures

[3 ] ’September 11, 2001’, Washington Post, 16

September 2001: http://www.washingtonposLcom/ac2/wp-dyn/A38407-2001Sep15

.

[4 ] ’DoD News Briefing on Pentagon Renovation’,

Defense Link, Department of Defense, 15 September 2001: http://www.defense1ink.mil/news/Sep2001/t09152001_t915evey.html

.

[5 ] ’War and Readiness’, All Hands, magazine

of the US Navy: http://www.mediacen.navy.mil/pubs/allhands/novOl/pg16.htm

.