Untitled Document

|

|

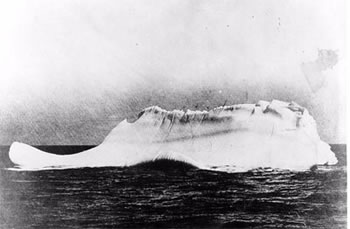

This is a black and white photograph of the iceberg with which the RMS TITANIC supposedly collided on April 14, 1912 at latitude 41-46N, longitude 50-14W.

|

The British-funded Ice Patrol is usually busy in May, protecting shipping

from rogue bergs. But it's all gone alarmingly quiet this year.

A mere 1,000 feet above the frigid waters of the North Atlantic the debate

began in earnest. The pilot of the US Coast Guard's sturdy C130 plane believed

the object which had appeared on both of the plane's radars was an iceberg.

One of two young but experienced ice observers on board disagreed.

To definitively identify the target, the plane started to descend to a mettle-testing

400 feet. This was part of the mission, and what is demanded of the staff of

the International Ice Patrol (IIP) by the hundreds of ships that traverse this

relatively small part of the ocean and rely on its findings for their safety.

Ever since the Titanic struck what was actually one of more than 350 icebergs

drifting amid the northern Atlantic shipping lanes in April, 1912, the US Coast

Guard has undertaken annual iceberg patrols to help protect passenger and freight

vessels that sail through the congested waters east of Canada and down the east

coast of America.

"Before we started there were 113 recorded sinkings caused by icebergs,"

says Michael Hicks, the present Commander of the International Ice Patrol. "There

have only been 19 since (omega) the Titanic sank, and all of those were vessels

that chose to ignore our warnings."

In the past, in a single year, more than 2,000 icebergs have been spotted,

tracked and on occasion ineffectually bombed by aircraft, in order to prevent

calamitous disasters at sea. Yet in other years, including this one, few if

any bergs manage to migrate south from the Arctic Circle. If the unidentified

floating object below the approaching plane is in fact an iceberg, it will be

the first one seen in the shipping lanes since May 2005 a situation perplexing

to oceanographers but emboldening to those shouting loudly about the effects

of climate change.

"I've been trying to understand the variability for years," says

Don Murphy the IIP's veteran oceanographer. "And every year that goes by

I get another year of experience and realise how little we really know."

After a century of study, there are still many unknowns regarding the movement

of icebergs and the reasons for the wide variability in the number that mischievously

make it into the 300-mile-long, 60-mile-wide area of the North Atlantic that

mariners refer to as "iceberg alley" due to the number of bergs pushed

through this part of the ocean by currents and underwater topographical features.

What is certain is that any that do make it this far south will be nearing

both the end of a three-year journey and their existence.

"When the bergs get this far south, their days are numbered," Hicks

says, explaining that the warmer waters of the Gulf Stream cause all icebergs

to ultimately melt, ensuring one less threat to ships and one less iceberg for

the IIP to monitor. What formed from 1,000-year-old ice atop the majestic ice

cap in Greenland ends up becoming an indistinguishable part of the ocean and

a sterile statistic in the Coast Guard's table of meddlesome bergs.

The International Ice Patrol is a unique organisation. A division of the US

Coast Guard, it is funded by 17 countries including the UK, and is the only

world body that constantly monitors icebergs that stray into the Atlantic shipping

lanes parallel to and south of Newfoundland. While the Canadian Ice Service

is dedicated to monitoring sea ice and icebergs in Canadian waters, and the

Danish Meteorological Service is concerned with bergs around its territory of

Greenland, the IIP has, since its inception in 1912, been charged with alerting

cross-Atlantic traffic to any iceberg threats.

"Almost immediately after the Titanic sank the US Navy assigned two cruisers

to the Grand Banks to patrol for icebergs and to let the ships know where they

were," says Hicks. "The following year the US Navy could no longer

spare the ships to do that so the Revenue Cutter Service, which was the predecessor

to the US Coast Guard, stepped up. The UK actually asked the US government,

since we had started doing this, to continue and, with the exception of the

World War years, we have been doing it ever since."

The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (Solas), a major

treaty governing merchant ships, mandates that all vessels crossing the North

Atlantic during the months when there is a threat from icebergs usually

February to July receive and read the IIP's notifications. However, they

are not compelled to act on them, hence the 19 sinkings that have occurred since

1913.

An iceberg (technically a piece of ice longer than 45 feet at the waterline)

has to make it past 48 degrees north a line of latitude that passes through

northern France in Europe before the IIP count it as having the potential

to interfere with shipping (the Titanic sank just south of 42 degrees north,

and icebergs have been spotted in waters as far south as those parallel to Washington

DC).

Surprisingly it wasn't until 1946 that the Coast Guard started using aircraft

to supplement its ships in the search for these monstrous and potentially lethal

pieces of ice.

"Up until that time it was just cutters," says Hicks. "Generally

they would assign two or three cutters and they would take turns going out from

Halifax or St John's, finding the southernmost iceberg and staying with it and

radioing their position to ships coming across the Atlantic."

The IIP stopped using ships in 1973, and has relied on aeroplanes ever since.

"The C130 aircraft can cover a much larger area in a lot less time,"

says Hicks. "They also have the capacity to carry side-looking airborne

radar which is an old but very effective radar system. It was designed to detect

oil spills but it works pretty well for icebergs."

The planes, which conduct 12 or more missions each month, normally fly for

six to eight hours at an altitude of between 5,500 and 8,000 feet, yet because

of the weather, even at that height, the sea is visible only 30 per cent of

the time.

"We will descend as low as 400 feet if we detect a target on the radar

that we can't identify and the cloud base is low," Hicks explains. "Hopefully

we will see the surface by that point."

Once an iceberg has been detected, its size and location are plotted on to

a map which is marked with the limits of all known ice. The map is then disseminated

to all ships crossing the Atlantic (more than a dozen a day) and is posted on

the IIP's website. To ensure a margin of safety, the line depicting the limits

of all known ice is usually drawn 30 miles south of the actual last known position

of an iceberg.

When the planes aren't flying, the maps are still updated every 24 hours.

"We forecast where we think the bergs are going using a computer model,"

Hicks says. "That model uses ocean currents, winds, water temperature and

waves to predict where the iceberg is going to drift and how long it is going

to take to melt."

Hicks admits the model is not flawless.

"In the short term it does a pretty good job," he says. "But

as you go beyond six or seven days it becomes less reliable, just like a weather

forecast, so that's why we patrol so often." Studies (omega) show that

icebergs generally drift distances of no greater than 12 miles in a day.

With three fifths of this year's ice season already over, not a single berg

has been spotted within 350 miles of the shipping lanes. Only once before, in

1966, has the IIP recorded zero icebergs in a season. There is no question the

low number of bergs is unusual.

"On average we expect to see about 450 icebergs a year," says Don

Murphy, who explains that all of the icebergs that appear in the North Atlantic

are produced by ice flowing slowly but steadily from glaciers in Greenland into

the sea and breaking away. The floating chunk of frozen water is then at the

mercy of ocean currents which initially carry it northwards and then westwards

across to Canada's Baffin Bay before the Labrador Current pushes it southwards.

"The currents are weak and variable along Baffin island so every iceberg's

southward track is characterised by long periods of no motion," says Murphy.

"Most will go aground on a pinnacle or submerged mountain around the edge

of the continental shelf and you have to wait for them to deteriorate until

finally they can float off the bottom and can continue their path. Then boom!

They get stuck again or get driven so far into a bay that they never make it

out and waves destroy them."

Murphy says that the ones that do make it less than one per cent of all

the bergs produced annually are "the ones with a shape that ensures

they aren't as sensitive to the wind's effects so they stay offshore or have

enough mass that even if they are grounded for a while, when they float again,

they are large enough that they still bring a substantial amount of ice with

them."

Those icebergs that survive all the way from the glaciers to the Grand Banks

take up to three years to make the 1,500-mile journey. Once there they will

be tracked by the IIP and left to disintegrate in the ocean. However, from shortly

after the Titanic sank and up until the 1960s, there was a belief that icebergs

could, and should, be destroyed.

"It was thought that if you shot a shell at an iceberg that the ice was

so brittle that it would just disintegrate," Murphy says. "The US

Navy attempted it but all they did was loosen a basketful of ice. Then they

decided to float mines against the sides of the bergs and blow them up but that

didn't work either."

Further attempts were made after the Second World War using larger bombs. "They

arranged to drop 1,000lb bombs on an iceberg. They hit it 17 times over a six-day

period but the end result was an insignificant change in the size of the berg

so they gave up. It was a silly idea and it was abandoned; the ocean does the

job perfectly."

Icebergs always succumb to warm water and warm weather but now there is considerable

debate as to whether climate change is playing any part in the fate or future

of these floating photogenic white sculptures.

"There is no doubt in my mind that major climate change is happening,"

says Murphy who has been a professional oceanographer for 22 years. "Studies

in Greenland show that the glaciers are moving twice as fast as before. That

means a lot of production of ice. My expectation has always been if the Greenland

glaciers started moving faster there would be increased production [of icebergs]

for decades and there should be an increase in the number of icebergs into the

shipping lanes. That was my model. But the last couple of years that hasn't

happened, and I'm having a hard time understanding what is going on except that

there are complicating factors having to do with increased storms. Maybe the

destruction processes dominate over the production processes."

The main destruction process is wave action. Icebergs that run aground are

the most vulnerable to sustained wave attack. In past years large concentrations

of sea ice have been thought to help icebergs remain afloat and prevent erosion

from waves.

In 2005, according to the US National Snow and Ice Data Centre, sea-ice cover

was at its lowest extent since satellite monitoring began in 1979, and this

year the IIP have noticed "very little although not an absolute minimum"

level of sea-ice conditions. Yet a computer model linking sea-ice levels to

the number of icebergs making it into the shipping lanes has performed "horribly"

according to Murphy.

So while climate change could be expected to bring about an increase in the

number of icebergs being forced into the ocean, its effect in reducing the level

of sea ice through increased sea temperatures could equally mean that those

icebergs liquefy long before they reach any areas of concern.

Yet, Murphy points out, that does not explain the huge discrepancy in the number

of icebergs recorded in years before climate change was an issue: e.g., 15 icebergs

in 1952; 1,500 in 1972. After thoroughly studying and analysing data from as

far back as 1900, Murphy can find no significant or consistent pattern in the

number of icebergs making it into the shipping lanes.

"It's a very complicated system and there are a lot of moving parts,"

he says, but he claims some people are eager to ascribe meaning to the figures.

"Back in the mid-1990s, when we had thousands of icebergs, I got a call

from Japanese TV who wanted to do a story on us because they believed the large

number of icebergs was indicative of global warming," he says. "Then,

in 1999, we had only 22 icebergs and I got a call from a European TV company

who wanted to do a story because they were certain that the fact that there

were only 22 bergs in the shipping lanes was a clear indication of global warming."

Murphy himself is reluctant to draw any conclusions from the changing number

of icebergs. Commander Hicks also believes the century-long variability precludes

any simple answers.

"There would have to be a decade of consistently light or consistently

heavy years to say something is happening here and we haven't seen that,"

he says. Nevertheless, only 11 icebergs were spotted in the shipping lanes last

year and they remain even more elusive this year.

This makes the debate on board the low-flying C130 all the more intense. As

the plane continues its descent through the clouds, seagulls are spotted atop

the floating white object. At 400 feet above the churning ocean, when the flight

crew and the ice observers can all see the object in detail through thick Plexiglas

windows, they realise it is, disappointingly, an inverted, dead Northern Right

whale.

"We'll keep looking," says Hicks. "We know there are icebergs

out there and maybe some will make it south before July." If they do, the

International Ice Patrol will certainly count them but they will happily leave

it to others to decide upon the significance of the number.

Chilling facts The truth about ice loss and global warming

By Adam Jacques