Untitled Document

Luke Frazza / Getty Images

Executive Summary Follows

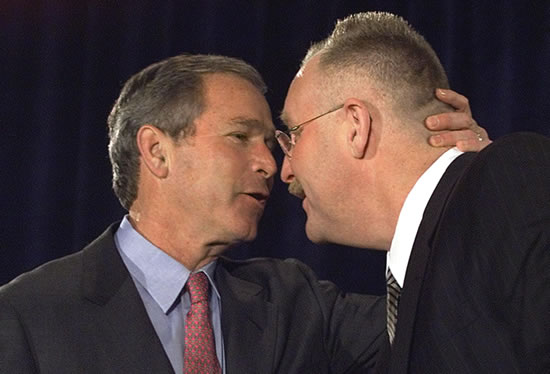

When George W. Bush came to Washington, he appointed his close aide and campaign

manager Joe Allbaugh to run FEMA. Allbaugh brought in as his first hire a little-known

fellow Oklahoman named Michael Brown. He promoted Brown quickly to be his top

assistant, then left the agency, making Brown the director.

When Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf States, Brown’s inexperience and

lack of qualifications quickly became apparent to the world. Reporters discovered

that Brown had substantially exaggerated his extremely modest accomplishments.

Bush initially expressed his support for the embattled Brown, famously declaring,

“Brownie, you’re doing a heck of a job.” But with criticism

reaching fever pitch, the president – famed for almost never jettisoning

subordinates – took the atypical step of forcing Brown out.

Little more was heard about Brown, or how such an inappropriate choice could

have ended up running an agency responsible for protecting the American public

from natural and manmade disaster, including the aftermath of terrorist attacks.

But a RealNews investigation, encompassing scores of interviews and hundreds

of documents, has unearthed a stunning back story that shines a bright light

on the mysterious Bush-Allbaugh-Brown relationship.

When Allbaugh brought Brown to Washington, he presented him as a lifelong associate

of high character and substantial credentials. “I hired him solely on

his ability as a strong ethics attorney,” Allbaugh said in an official

FEMA press release at the time. “He is very experienced, knowledgeable,

and professional and will be a great asset to the agency and to myself.”

The truth, RealNews has learned, is that the relationship between the two rests

on a decades-long hidden partnership designed to advance both men's business

and personal interests. By all appearances, that relationship drove Allbaugh's

decision to ask Bush to let him run FEMA, and his decision to turn the place

over to Brown so he could profit from their ties.

The full 9000-word article is readable here. Among the key revelations:

-Once in Washington, Allbaugh and Brown characterized themselves as long-time

friends, and were content to leave the impression that they knew each other

from college and Republican circles. But lifelong associates of both men say

that is untrue. Indeed, the association between the two appears to have been

a largely covert one, based less on selfless brotherhood than on mutual self-interest,

as represented by a series of murky business ventures.

-Both Brown and Allbaugh were accused in the past of fiduciary malfeasance.

Before coming to Washington, both were known to associates and creditors not

as rising stars but as ethically-challenged, and frequently failed, entrepreneurs.

-In one business venture, Allbaugh worked for Brown, as a lobbyist. In another,

Allbaugh partnered with Brown’s brother-in-law and sister-in-law. That

business involved mysterious, large amounts of cash that upset Allbaugh’s

then-wife, and contributed to their divorce. One Allbaugh business partner would

later be convicted of mail and wire fraud and serve time in a federal prison.

-Allbaugh persuaded an elderly widow who was a frequent GOP donor to personally

loan him money; he defaulted on the loan.

-Allbaugh and his second wife declared bankruptcy, unloading nearly $300,000

in debt, but failed to report this – as he was required to do –

to the Senate on disclosure forms during his confirmation process. Legal experts

say this may constitute a felony.

-Allbaugh accepted a personal loan guaranteed by a large contractor doing business

with the state of Oklahoma while he was a top aide to the governor; he never

repaid the loan.

-Brown, who was brought into FEMA initially by Allbaugh to run the legal operation,

has a history as a failed low-level lawyer, replete with discontented clients,

unhappy employers and damaging lawsuits.

-Brown was fired from his longest-held position, his principal job preceding

his hiring at FEMA, for obtaining a personal loan from a prominent horse owner

under false pretenses. When an official of the horse association confronted

him, Brown tried to make a deal with the man to make the matter go away.

-Although it has been reported that Brown exaggerated some of his accomplishments,

he actually exaggerated many more, creating a misleading impression about his

qualifications and his credibility as he was confirmed to his high federal position.

-The hard-luck Brown has received multiple assists from well-connected Republicans.

His long-time lawyer, who has helped him through scrape after scrape, is a friend

of Clarence Thomas and former regional director of the influential and secretive

Federalist Society.

-Brown and Allbaugh had apparently agreed on Brown’s role in the Bush

administration well in advance. For six months prior to Bush’s election

in 2000, Brown was telling incredulous associates that he expected to land a

high position in Washington.

-Both Allbaugh and Brown appear to have withheld negative personal financial

information from the Senate during their confirmation process – information

that would have cast doubt on their fitness for high office and that, by law,

they were required to disclose. Allbaugh, notably, failed to disclose his 1990

bankruptcy.

-At FEMA, Allbaugh launched a purge, forcing out many of the most experienced

officials. Allbaugh and Brown also abandoned a recent agency tradition of hiring

experienced professionals and filled high FEMA positions with political operatives

lacking familiarity with emergency disaster management.

-Allbaugh edged out his #2, one of the most experienced men in government,

in order to replace him with Brown.

-Under Brown, during the 2004 presidential election, FEMA handed out tens of

millions of dollars in disaster aid in parts of the politically crucial Florida

that had experienced little damage.

-Allbaugh has had extremely close ties with Vice President Cheney – including

vetting Cheney for the vice presidency, buying his house, serving on Cheney’s

secretive energy task force, and then becoming a consultant to Cheney’s

former company, Halliburton.

-Under Allbaugh and Brown, FEMA changed the way in which the agency handled

contracts, awarding them to numerous firms with political connections but little

in the way of corporate infrastructure to handle the work. Some of these recipients

were merely Enron-style shell corporations that subcontracted all the work to

others, keeping a sizable share of the profits.

-When Allbaugh left FEMA, he immediately began setting up a network of lobbying

interests to benefit from his connections. His clients were selected by FEMA

under Brown, and by other agencies, for major contracts.

-FEMA shifted abruptly in 2003 from dealing directly on a non-exclusive basis

with large bottled water suppliers, to issuing a sole-source contract to a tiny,

politically connected firm that had to turn to other companies to supply water.

This arrangement is blamed for substantial problems with deliveries of water

following Hurricane Katrina.

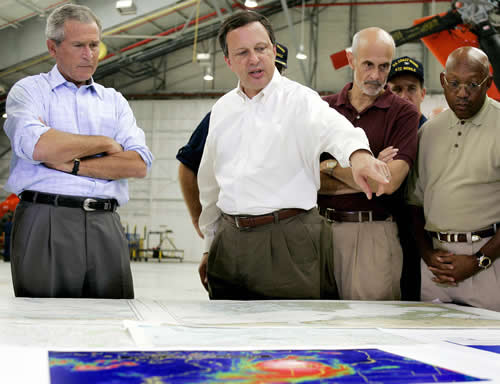

FEMA Director Michael Brown explains Katrina situation to President George W. Bush and Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff. Jim Watson/Getty Images

Unholy Trinity: Katrina, Allbaugh and Brown

Days after Louisiana’s governor declared a state of emergency and the

National Hurricane Center warned the White House that Hurricane Katrina could

top the New Orleans levee system, the only FEMA official actually in New Orleans

itself— Marty J. Bahamonde —was not even supposed to be there. He

had been sent in advance of the storm and had been ordered to leave as it bore

down, but could not because of the clogged roads. Michael Brown, the head of

FEMA, was known to have made it to Baton Rouge but seemed out of reach.

On Wednesday, Aug. 31, with tens of thousands trapped in the Superdome and

looting out of control in the parts of the city still above water, Bahamonde

e-mailed Brown directly: ''I know you know, the situation is past critical…Hotels

are kicking people out, thousands gathering in the streets with no food or water.'''

The response, when it came several hours later, was from a Brown aide, and did

not address the warnings, but noted Brown’s desire to appear on a television

program that evening. It included this key caveat: ''It is very important that

time is allowed for Mr. Brown to eat dinner.''

A week later, Brown would be replaced as on-site manager of the disaster. Blamed

for his role in one of the largest domestic debacles in American history, Brown

was still thinking of his own comfort: "I'm going to go home and walk my

dog and hug my wife, and maybe get a good Mexican meal and a stiff margarita

and a full night's sleep," he told AP. In the midst of America’s

worst natural (and manmade) disaster, it became clear that Brown was indeed

lost in Margaritaville.

What has grown all too apparent in the months since Katrina is that much of

the Bush-appointed federal leadership is every bit as inept and unqualified

as Brown. Each new crisis seems to expose still more cronyism and patronage

at the very top of the country’s leading agencies. The Medicare administrator

Thomas Scully came from a job with the hospital association, stayed just long

enough to pass the controversial and messy if business-friendly Medicare drug

benefit, then left to become a drug industry lobbyist. Other stories are emerging

at departments ranging from the Small Business Administration to the Mine Safety

and Health Administration. And the head of the White House Office of Federal

Procurement Policy had no prior experience in government contracting; he has

since been arrested in connection with the sprawling corruption investigation

surrounding lobbyist Jack Abramoff.

From Harriet Miers (a Supreme Court nominee with no judicial experience) to

Julie Myers (a virtual government neophyte named to head the Immigration and

Customs Enforcement agency), Bush has set aside principles of sound governance

to reward loyal operatives and shore up personal and party alliances. Sometimes,

his tactics are transparent. Miers was a longtime legal adviser and trouble-shooter

to Bush; and Myers, the niece of the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of

Staff, had at the time of her nomination recently married the chief of staff

of her boss-to-be, Homeland Security secretary Michael Chertoff.

We still do not know the true extent to which the government has been filled

with Michael Browns. This is in part because of the media. At one time, major

news organizations had a reporter assigned to each large federal bureaucracy,

making it harder to sail these appointments through and then hide the incompetence

and malfeasance. Now only a disaster can shine the spotlight.

But Michael Brown will forever remain the poster child for federal incompetence.

And the central question has yet to be answered: who was Michael Brown, and

how did he end up at the helm of the Federal Emergency Management Agency? Indeed,

how did he and his predecessor and mentor, Bush political operative Joe Allbaugh,

manage to turn FEMA, a once proud and effective agency, into a national laughingstock?

On any level, it makes absolutely no sense that Michael Brown should have been

holding any major government post. Prior to joining FEMA, his professional pinnacle

had been to serve as an inspector of Arabian Horse judges; his highest governmental

job had been an assistant to a city manager in a small Oklahoma city decades

ago.

"Brownie" had done no known political work for George W. Bush. He

was not an industry figure. He was not even among the many longtime allies of

the Bush family. The only answer the public has ever gotten in the aftermath

of Katrina as to why Michael Brown headed the Federal Emergency Management Agency

was a peculiar and highly dissatisfying one: Joe Allbaugh wanted him there.

Allbaugh is the brash and powerful but little-known Bush confidant who preceded

Brown as FEMA director. When Allbaugh came to Washington, he brought Brown with

him and rapidly promoted him until Brown was positioned to take over the agency.

But why Michael Brown? Why, out of all the people Allbaugh had met over three

decades as a GOP operative, did he place such confidence in a failed lawyer

whose last job was a troubled tenure with an obscure association of show horse

owners?

When pressed, the taciturn Allbaugh tersely replied that Brown was a lifelong

friend in whom he had confidence. To this moment, that has remained the official,

indeed only, explanation of how and why Michael Brown was running FEMA when

Hurricane Katrina struck.

But a Real News Project investigation, encompassing scores of interviews and

hundreds of documents, has uncovered another reality. It begins with this astonishing

fact: nearly all of Joe Allbaugh's friends and acquaintances say they had never

heard of Michael Brown, never met him, never even seen the two men in each other's

presence. To them, Michael Brown is a complete stranger. Allbaugh's explanation

of why he chose Brown as his heir apparent at FEMA baffles one and all.

The truth, RealNews has learned, is that the relationship between the two is

a decades-long hidden partnership designed to advance both men's business and

personal interests. By all appearances, that relationship encompassed Allbaugh's

decision to ask Bush to let him run FEMA, and then his decision to turn the

place over to Brown so he could profit from their ties.

Indeed, as soon as Allbaugh left the agency, he began cashing in. Today, both

Allbaugh and Brown are consultants, making money off their connections at FEMA

and in the administration—tattered and tarnished though their legacies

may be. And now FEMA is staffed by others put into position by the two men and

run by David Paulison, best known for having advised Americans to stock up on

duct tape as protection against future terrorist attacks.

Is this really just about incompetence as a byproduct of a deeply ideological

presidency? Or has a debilitating "culture of corruption" become deeply

embedded in agencies like FEMA on which we literally rely for our lives? And

just how far into the Bush White House does this dismaying story reach?

Click here to

view original supporting documents

MEANWHILE, DOWN AT THE PADDOCK

Jocelyn Augustino / FEMA Photo Library

In a more perfect world, the media, the Congress and engaged citizens would

have wanted to know a bit more—indeed a lot more—about Joe Allbaugh

and Michael Brown before confirming them in important managerial positions.

Even a hard look at Brown’s last job before FEMA would have set off the

appropriate alarms.

Brown's decade as Commissioner of Judges and Stewards of the International

Arabian Horse Association (IAHA) represents the longest employment he ever had,

and, arguably his most prestigious and greatest accomplishment. That Brown nevertheless

knew it was a singularly inappropriate qualification for the leadership of FEMA

is evident from FEMA's official Brown biography, posted on its website, which

did not mention this job at all. Brown, it turns out, had good reason to be

modest about this portion of his career.

When the new post into which Michael Brown stepped at IAHA was created, the

organization's members were told that their leadership had sought out a person

with several key characteristics: competency, experience, and total independence

from the cronyism of the horse world.

In fact, what IAHA members got was the virtual opposite. In retrospect, it

looks to some like the fix was in.

Brown's job was to address concerns about the integrity of the horse judging

process. But the main thing—almost the only notable thing—Brown

did in his years with the IAHA was to pursue a politically-motivated investigation

of the sport’s most successful trainer, a man who had angered powerful

people with connections at the top of the Republican Party.

Karl Hart, a Florida lawyer and longtime IAHA member who headed the group's

legal review committee, describes Brown's efforts in this regard as an “obsessive

vendetta.”

The trainer, David Boggs, was accused of cosmetically altering the appearance

of a show horse, a serious violation of competition rules. Brown ordered Boggs

banned from the show circuit for five years, a Draconian punishment tantamount

to putting the trainer out of business. Boggs’s competitors were delighted.

David Boggs (who did not respond to interview requests) was, by most accounts,

a talented and dedicated trainer whose successes on the circuit were well deserved.

But according to Hart and others, he was envied and even hated by several extremely

rich Arabian Horse owners—owners who happened to also be very large Republican

donors, including the late Bob Magness, a founder of the TCI cable giant; David

Murdock, the Dole food company billionaire; and the late Alec Courtelis, a Florida

developer.

Courtelis had been one of George H.W. Bush’s major fundraisers, and the

elder Bush was a frequent guest at Courtelis’s horse farm during his presidency.

At an April 1990 fundraising dinner in Florida, Bush introduced Courtelis with

the words “Here’s a man who breeds race horses for the same reason

he works so hard for the party: only one place will do for Alec—first

place.”

To this day, Hart (along with other longtime IAHA elders) says he’s not

sure whether or not Boggs was guilty. (IAHA's top administrators declined requests

for interviews about Brown.) Since the horse in question is today the preeminent

sire of the breed, Hart thinks genetics may have been more of a factor in its

near-perfect profile than the putative illegal cosmetic surgery. In any case,

Boggs filed a battery of lawsuits against both the association and Brown, the

financial toll of which contributed to the association’s near-bankruptcy

and eventual merger with another group.

There is no evidence that the big donors knew in advance about plans to hire

Brown; Courtelis and Magness are deceased, and Murdock did not respond to an

interview request. Yet, Brown's performance clearly pleased influential sectors

of the IAHA, as is apparent from the special treatment he was accorded. While

other staffers had to report to work each day, Brown, on a full salary, was

allowed to work from his sprawling, mountain-air home in Lyons—more than

an hour’s drive north of IAHA’s headquarters in Denver. His lifestyle

was so pleasant and relaxed that some in Lyons assumed him to be semi-retired.

James Van Dyke, chef-owner at Lyons’ Gateway Café, says Brown had

leisurely lunches at the restaurant almost daily. “He seemed to have a

lot of time on his hands,” says Van Dyke.

Brown’s single-minded pursuit of Boggs contrasted sharply with a pronounced

reluctance to pursue another case that seemed to have considerable merit—one

involving Murdock’s trainer, who was accused of filing false papers for

a show horse.

Ironically, it would be Murdock himself, in his zeal to help Brown’s cause,

who would eventually sink him. One day, he mentioned to Hart that, at Michael

Brown’s request, he’d written him a $50,000 personal check, ostensibly

for a legal-defense fund to deal with Boggs's suits. Hart was staggered to hear

this, since the association was already paying Brown’s legal bills.

Hart took Brown aside at an IAHA board meeting and told him what he knew. Brown

panicked. “He grabbed me, literally, and pushed me into a closet,”

says Hart. “He said, ‘Is there any way you and I can work this out?’”

There wasn’t, and Brown was terminated immediately.

But only a few months later, in February, 2001, he resurfaced— as general

counsel and later deputy director and chief operating officer of the vast bureaucracy

at FEMA (his positions before he took over the agency altogether.)

While most folks who knew Brown over the years were startled to see a person

of such modest accomplishments in a high Washington post, the IAHA brass was

not. As Hart recalls, “Brown had been saying for six months or more that,

if Bush was elected, he was going to have a high position in Washington because

he was very close to someone who was very active in Bush’s campaign.”

HOW MIKE MET JOE

Alex Plummer / FEMA Photo Library

Why exactly would this apparent incompetent be tapped for one of the most sensitive

jobs in post-9/11 Washington? The key to that mystery lies in the career of

Joe Allbaugh, George W. Bush’s adjutant since 1994, who first met Brown

back in the 1980s when both were young men starting out professionally in Oklahoma.

Typical of those baffled by the revelation of Allbaugh and Brown’s mutually

beneficial business and personal relationship is Mike Williams, one of Allbaugh’s

closest friends and a boating buddy. Williams, who stays in regular touch with

Allbaugh, says he doesn’t know Brown at all. As to Brown’s appointment

at FEMA, “I’m surprised by that.” Williams says Allbaugh never

had an entourage he could have brought along to Washington: “He didn’t

really have any people. He was pretty much a one-man show. (Neither Allbaugh

nor Brown consented to an interview.)

Contrary to early, widely-disseminated news accounts, Allbaugh, 53, and Brown,

51, were not college roommates — nor did they even attend the same university.

The two men's public lives and career paths up until FEMA look like parallel

lines on a chart — distinct and unconnected.

Yet there was a connection, one that only showed up through extensive records

searches.

The Real News Project has uncovered documents showing that, in the early 80s,

as Brown was finding his professional footing and Allbaugh was already rising

in the Oklahoma Republican apparatus, Allbaugh moved into an Oklahoma City house

next door to the brother of Michael Brown's wife, Tamara. Bill Oxley, Michael

Brown and Tamara Oxley Brown had all grown up together in the small Oklahoma

Panhandle town of Guymon. (Bill Oxley’s telephone number is unlisted;

he did not respond to a note left at his house requesting an interview)

The first verifiable direct link between Allbaugh and Michael Brown is in an

obscure company called Campground Development Corporation, which Brown and his

brother-in-law, Bill Oxley, formed in 1985. For two years, records show, Campground

Development employed Joe Allbaugh as a state capitol lobbyist. Prior to that,

Allbaugh himself had started an oil-and-gas partnership called Great American

Resources, and brought in Bill Oxley's wife as a partner. The secretary and

treasurer of that firm was Allbaugh’s then-wife, Gypsy Hogan, who says

she had no idea what the business was about and wasn’t comfortable with

large amounts of unexplained cash flowing in – or Allbaugh’s request

that she sign a series of blank checks. When she began to demand answers, she

says, Allbaugh angrily warned her to mind her own business. Hogan also remembers

that, shortly before she asked him for a divorce, Allbaugh claimed to be in

the C.I.A.

As Allbaugh was pursuing his private ventures, he was also moving up in the

G.O.P. firmament. He’d started in college as a driver for U.S. Senator

Henry Bellmon (Republican of Oklahoma and longtime friend of George H.W. Bush),

then became Bellmon’s field representative before becoming an operative

for the national Republican Party. In 1976, he held a top post in the statewide

Ford for President campaign. By 1980, Allbaugh was traveling widely, working

on campaigns throughout the country; in 1984 he rose to be deputy regional coordinator

for the Reagan-Bush reelection campaign, responsible for 11 Western States.

That year, by his own account, he met George W. Bush, who was in Oklahoma City

on behalf of his father’s campaign.

As Allbaugh was helping elect Republicans, he was also helping himself along

the way. Among his investors in Great American were several big GOP donors,

including Mabel McPhaill, a wealthy widow from Visalia, California. According

to her grandson, Russell Gates, who accompanied her to several fundraising events,

“All she did was give money.”

But not just to the GOP. Records obtained by The Real News Project show that

in 1984, while running the regional Reagan-Bush reelection campaign, Allbaugh

personally borrowed $24,000 from McPhaill. He never repaid the bulk of the debt.

When McPhaill died in 1996 at age 92, her $3 million inheritance had shrunk

to a net worth of $50,000 — with much of her fortune, according to Gates,

being enticed into GOP causes and dubious investments like Allbaugh’s.

It is doubtful whether, prior to his meeting George W. Bush, Allbaugh’s

business ventures ever made money for anyone, himself included. Archives in

Fort Worth, Texas, contain a file from 1990 detailing bankruptcy proceedings

in which Allbaugh and his second wife, Diane, unloaded nearly $300,000 of debt,

ranging from a $65,000 home loan to a $400 balance on a Foley’s Department

Store charge card – while their gross income was over $80,000 annually.

Allbaugh neglected to disclose the bankruptcy and related lawsuits during the

Senate hearing to confirm his appointment as FEMA director, in 2001. On a sworn

disclosure form, when asked whether he had ever been a party to any administrative

proceeding or civil litigation, he simply wrote “no.” That’s

a potentially problematical answer, and of heightened relevance since Cheney

aide Scooter Libby’s indictment on charges of lying to a grand jury and

to investigators. Says G. Jack Chin, an expert on testimony and Co-Director

of Arizona University’s Law, Criminal Justice and Security Program: “People

don’t forget going bankrupt, so I’d think a strong case could be

made for perjury.”

That Allbaugh would not want his insolvency made public is unsurprising. As

George W. Bush’s campaign manager, he would preside over a record-breaking

fundraising spree engorged on promises to credit issuers that new laws would

make it more difficult for ordinary citizens to declare bankruptcy. He also

might have faced scrutiny over some of his business associates: Grant Forth,

another limited partner in Great American Resources, would later be convicted

in a Nevada federal court of mail and wire fraud and serve time in federal prison.

In Oklahoma, Allbaugh was perhaps best known for his fearlessness in pursuing

deals that raised grave conflict-of-interest questions. In 1987, he was again

working for Henry Bellmon, now governor of Oklahoma, as a top aide who interacted

with highway officials. In December of that year, court records show, Allbaugh

took a $30,000 bank loan guaranteed by a large road contractor who was engaged

in a steady stream of disputes with the state over shoddy work practices. Allbaugh

never repaid the loan and in 1990 the court ordered that his wages be garnished.

Neal McCaleb, the man who ran Oklahoma’s Transportation Department at

the time, would later be appointed by President George W. Bush as U.S. Assistant

Secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs. (Shortly thereafter, Allbaugh’s

wife would be accused by a McCaleb subordinate of improperly lobbying McCaleb,

a Chickasaw Indian, on behalf of client tribes seeking beneficial gaming decisions.)

From there, the stakes got higher. In 1988, Allbaugh left government to take

a job with Stephens Inc., an investment-banking firm run by an old Bellmon friend.

When Allbaugh arrived, Jack Stephens was busy currying favor with Vice President

George H.W. Bush, then likely to be elected president. He gave $100,000, the

legal maximum, to Bush’s campaign and helped bail out the vice-president’s

son, George W. Bush: it was Stephens who helped arrange for a Saudi oil magnate

to buy an ownership stake in Harken Energy, W.’s oil company, which was

struggling to stay afloat.

Allbaugh’s ability to hop back and forth between the letting and the

getting of contracts was clear to all—including Allbaugh himself. When

a reporter from the Daily Oklahoman observed to Allbaugh that he had gone from

serving as Bellmon’s Oklahoma Turnpike Authority liaison to working for

Stephens Inc., which was hoping to do business with the Authority, Allbaugh

replied, “Golly, what a coincidence.”

In September 1990, Allbaugh left Stephens for reasons unknown. His resume suggests

that he was then unemployed until February, 1991, when he reappeared back on

the other side of the customer-service counter, this time as deputy secretary

of transportation under Democratic governor David Walters. (A grand jury later

issued eight felony indictments against Walters, who pled guilty to one misdemeanor

charge of violating state campaign-contribution laws.)

Allbaugh’s arm's-length friend Brown, meanwhile, was racking up his own

record of dubious public service throughout the late 1970s and 1980s. In his

much remarked-upon first job, as assistant to the city manager of Edmond, Oklahoma,

he was closely allied with the town’s mayor, Carl Reherman, who had been

Brown’s political-science professor in college. His immediate boss from

those days, city manager Bill Dashner, characterized Brown as a "mole"

for Reherman, providing him with information regarding controversial development

projects over which the two quarreled. In an interview, Reherman denied that,

and noted that the council voted unanimously on most matters. Perhaps the biggest

bone of contention over the years was a public-works project that became so

expensive the city defaulted on its payments to the Army Corps of Engineers—the

same highly politicized outfit with which FEMA is joined at the hip. Brown did

not mention this experience during his confirmation hearings.

(Brown would later be exposed, during the Katrina debacle, for having tried

to exaggerate his credentials for FEMA by falsely telling the Senate that he

was an “assistant city manager,” responsible for police, fire, and

emergency services. As negligible as this position sounded, in truth, he’d

been even less, a mere assistant to a city manager—“more like an

intern,” the town’s P.R. liaison told Time.)

Whether he began as gopher or go-getter, Brown moved quickly after his arrival

in Edmond into a series of posts of increasing influence, including election

to a short stint on the city council and a job with the state legislature, where

he helped draft legislation creating the Oklahoma Municipal Power Authority

(OMPA), a little-known public-power entity that he would later chair. The attraction

of this unpaid position was explained by Brown, who noted to others that it

allowed him to interact with major bond-underwriting firms, all clamoring for

the group’s lucrative business. When Brown was forced to relinquish his

seat on the utility board because he had moved from Edmond, he found his way

back by persuading the town of Goltry, Oklahoma, population 800 and one stop

light, to join the energy consortium and make him its representative.

In a questionnaire he supplied to the Senate during his confirmation process,

Brown wrote: “Michael D. Brown Hydroelectric Generation and Dam Project

Named in my honor by the Oklahoma Municipal Power Authority Kay County, Oklahoma,

1988.” That minor tribute (dubbed by one wag “Dam Michael Brown”)

would amount to his sole pre-Katrina familiarity with the subject of flood control.

But according to the longtime OMPA general manager, Roland H. Dawson, the facility

itself is actually called Kaw Dam, while the only tribute to Brown is a plaque

from the board he chaired.

After passing the Oklahoma bar in 1982, Brown moved to the oil boomtown of

Enid, where he was hired by the law firm of Stephen Jones, a flamboyant attorney

who went on to defend Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh. There, according

to his other sister-in-law, Brown bobbled a wrongful-death suit for a woman

whose husband’s car was hit by a train when crossing signals failed to

work. When the firm busted up, literally, after a fistfight that left Jones

sporting a shiner on the front page of the local paper, the partners divvied

up the staff. Thirty-four staffers found immediate work. Brown was one of two

staffers no one wanted. “When I saw Brown up there at FEMA, I had a premonition

of bad things to come,” recalls Jones.

In the ensuing years, Brown would be sued for skipping out of shared law offices

without paying his share of the rent—a piece of civil litigation he (like

Allbaugh) neglected to include on forms submitted as part of his Senate confirmation

proceedings to become deputy director of FEMA. This despite the obligation that

federal nominees disclose such litigation. He would also be believed by his

sister-in-law to have aided her brother, Bill Oxley, in changing their father’s

will in a way that left the Browns and Oxleys living well while she and her

husband were reduced to virtual paupers. During those years, if Brown's resume

is to be believed, he was also doing legal work on behalf of the Oklahoma Republican

Party.

All of this was, of course, mere cold French fries compared to what would come.

For Michael Brown, the good times would not begin to roll until early 2001,

with a call from Joe Allbaugh. For Allbaugh himself, the good times began in

early 1994, with a call from George W. Bush.

BUSH’S ENFORCER

The official story is that Bush’s gubernatorial campaign lacked a strong

hand at the tiller, and that Henry Bellmon’s people recommended Joe Allbaugh

as just the man to steer the campaign to victory. “He said he’d

been involved in campaigns in 37 states by the time he got to Bush,” says

Dave McNeeley, a former political columnist for the Austin American-Statesman.

Whether that was literally true seemed less important than the ties Allbaugh

claimed to Bush’s father, who in 1992 appointed him to something called

the Arkansas-Oklahoma Arkansas River board. George W.’s father had an

eye for problems that might sneak up on his kids—and for identifying people

who could help make the problems go away. (The elder Bush's office did not reply

to a request for an interview.)

In newspaper articles, Allbaugh explained his role in the Bush gubernatorial

campaign as making sure the trains ran on time, and mediating the strong personalities

of Karl Rove and Karen Hughes. To Bush’s Brain and Bush’s Mouth

was added Bush’s Muscle. At 6-foot-3 and 275 pounds, Allbaugh was an intimidating

presence. Some would later liken him to the blockish Sergeant Schultz on the

classic TV show Hogan’s Heroes, who used to utter, “I see nuuussing,”

while surrounded by mischief.

“It was clear he wanted to use his size to project a strong or menacing

sense of himself,” says Wayne Slater, Austin bureau chief for the Dallas

Morning News. Indeed, Allbaugh’s propensity to turn bright red when enraged

led Bush to give Allbaugh the nickname “Pinky.” But if anyone other

than W. dared to call him by that name, Allbaugh would whirl around and growl,

“I will pinch your head off,” and make pinching motions with his

fingers.

His loyalty to Bush, a man who prizes that quality above all others in his

subordinates, was unquestioned. “There isn’t anything more important

than protecting him and the first lady,” Allbaugh once told the Washington

Post from the governor’s office. “I'm the heavy, in the literal

sense of the word.”

Ironically, the other heavy was a small, refined woman by the name of Harriet

Miers, hired, as was Allbaugh, by the tough Dallas lawyer Jim Francis, then

Bush’s campaign chairman and a longtime friend of Bush’s father.

As general counsel, Miers was in charge of fending off legal problems that threatened

Bush with adverse publicity.

In 1999, Allbaugh left the governor’s office to take over the daily management

of Bush’s presidential campaign. He headed up a staff of 180, controlled

spending, and spoke with Bush several times a day.

One potential problem facing the campaign was the rumor that Bush’s father

had pulled strings to get his candidate son out of Vietnam service and into

a safe Texas Air National Guard unit in 1968. There were even reports that Bush

went AWOL long before his compulsory flying days were up.

The key players in keeping the lid on the National Guard story were Allbaugh

and Miers. In 2004, a year before Bush nominated Miers for the Supreme Court,

Allbaugh told The New York Times, “She’s the kind of person you

want in your corner when all the chips are being played.” Assigned to

“investigate” Bush’s Guard service, Miers gave the governor

a clean bill of health.

As part of his job, Allbaugh communicated directly with Adjutant General Daniel

James III, the head of the Texas National Guard (later appointed by President

George W. Bush to run the federal Air National Guard). What remains unclear

is whether he ordered James to dispose of any old Bush military files that might

prove embarrassing, an order former Lieutenant Colonel Bill Burkett, head of

a Guard efficiency task force, claims to have heard Allbaugh issue in a conversation

on James’s speakerphone. Whatever was or was not done, the unexplained

gaps in Bush’s National Guard service never became a central topic in

the 2000 election. With his “iron triangle” of Rove on strategy,

Hughes on P.R., and Allbaugh as the enforcer (plus an assist from the U.S. Supreme

Court), Bush triumphed.

Meanwhile, the unsinkable Michael Brown rebounded once again, this time from

his firing at IAHA. Just as the politics-tinged Horse Association job in Colorado

appeared when Brown faced career and financial problems in Enid, Oklahoma (and

the Stephens job fell into Allbaugh’s lap when his financial difficulties

mounted), Brown would be fortuitously safety-netted again, this time with a

near-instantaneous hiring by an anti-union electrical contractors’ association

that later won warm praise from President Bush.

Another constant in Brown’s bumpy career has been timely assists from

his self-described “longtime friend and family attorney,” Andrew

Lester. A prep-school contemporary of George W.’s brother Marvin, Lester

pops up at crucial points in Brown’s life like a fairy godmother. When

Brown lost an early legal job, Lester brought him in for a brief stint as his

law partner. When horse-association problems engulfed Brown, Lester rushed to

his defense. And on September 27, 2005, at a House select committee hearing

investigating the Katrina blunders, there was the pin-striped Lester conspicuously

whispering legal advice in Brown’s ear. Lester, who represented the Oklahoma

Republican Party in a 2002 reapportionment battle, worked for a Bush-family-connected

oil services firm when he was younger, has been a close friend of Justice Clarence

Thomas and regional director for the secretive Federalist Society (new Chief

Justice John Roberts denied being a member until his name turned up on a list);

he was also short-listed for a federal judgeship under George W. Bush. To this

day, Lester insists his support is merely a factor of friendship, and maintains

that Brown was eminently qualified for FEMA.

CHOOSING FEMA

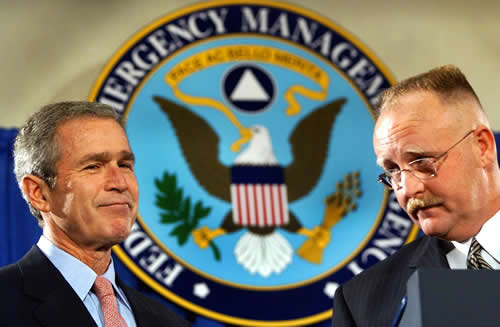

President George W. Bush and FEMA Director Joe Allbaugh. Paul J. Richards / Getty Images

As Bush’s Texas team headed for Washington, it was clear that Joe Allbaugh

had neither the experience nor the sophistication to serve as the White House

chief of staff, the position he coveted. That job went to Andy Card, who had

served in the senior Bush’s administration. CNN quoted a “source

close to the transition team” who predicted that Allbaugh would become

one of two deputy chiefs of staff. Instead, he landed at FEMA.

But why there? Theories abound. Some speculate that Allbaugh wanted to stay

in the White House but that Rove wanted the brusque enforcer out of his way.

Some of Allbaugh’s friends say he had grown tired of being at Bush’s

beck and call and wanted to “do his own thing.”

If it was a fiefdom he was after, FEMA would do nicely. Allbaugh had enjoyed

being the governor’s interface with emergency agencies during minor crises

in Texas. At FEMA, he would have more than 8,000 employees and a $4 billion

budget to play with. The selection was made, and Allbaugh, having failed to

reveal his bankruptcy, his lawsuits, and the general messiness of his life up

to that point, was confirmed by the Senate with minimal scrutiny.

From its inception under Jimmy Carter, FEMA had traditionally been patronage

territory. George H.W. Bush appointed Wallace Stickney, a former next door neighbor

of Bush Chief of Staff John Sununu, who had headed New Hampshire's Department

of Transportation and been an EPA engineer. Stickney presided over FEMA’s

inept handling of Hurricanes Hugo and Andrew during the first and last years

of the elder Bush’s term, events that many political observers believe

contributed to Bush’s loss to Bill Clinton in 1992.

Clinton introduced reforms at FEMA and appointed his former head of disaster

management in Arkansas, James Lee Witt, as director (which was elevated to a

cabinet-level position.) Witt communicated confidence in his agency, its role,

and its personnel, and FEMA morale soared. Republican Senator Ted Stevens sought

to keep Witt on indefinitely, drafting legislation to make the FEMA directorship

a longer-term, fixed position. Even George W. Bush praised Witt, leading many

to hope that Bush might keep him on. But the candy store was simply too big

to leave to a holdover from the hated Clinton administration.

When Allbaugh took over, Witt introduced him around the offices. He went out

of his way to praise the staff of the 8th-floor, which contained the front office,

congressional affairs, and other key sections. “Apparently, that was the

kiss of death,” says a former official who worked on that floor. “From

then on, we were not to be trusted.” The new boss made it clear from the

day he arrived that he had little regard for many of his underlings. “Joe

Allbaugh didn’t trust many people,” says Trey Reid, a former senior

FEMA official. “He was very insular, and had a tight circle.”

The first person Allbaugh brought into that circle was Michael Brown, who,

as general counsel, presided over a legal staff of 30. Allbaugh insisted there

was no one better suited than Brown. “I hired him solely on his ability

as a strong ethics attorney,” Allbaugh said in an official FEMA press

release at the time. “He is very experienced, knowledgeable, and professional

and will be a great asset to the agency and to myself.” With emphasis

(as would soon be clear) on “myself.”

The front office was Allbaugh’s bunker. Abandoning a tradition of using

civil-service professionals for certain vital posts, he quickly staffed up with

loyalists. These included Deputy Director Patrick Rhode, Deputy Chief of Staff

Scott Douglas, and Acting Deputy Chief of Staff Brooks Altshuler, all political

operatives with no professional experience in emergency disaster management.

Holdovers from Witt’s tenure, meanwhile, mistrusted Allbaugh in turn,

and in some cases even withheld information he’d requested. “In

one meeting, Joe made it clear he would have fired everyone if he had his way,”

recalls Reid. “If the elevator doors opened [with Allbaugh inside], employees

wouldn’t get on. They were afraid of him.”

One senior staffer who did get on an elevator with the hulking Allbaugh made

the mistake of complimenting his boss on his fine performance on Meet the Press

that weekend. “Why would you care?” Allbaugh snapped.

Allbaugh soon embarked on a Nixonian purge. Acting upon his orders, a reluctant

inspector general launched a series of internal investigations, looking at everything

undertaken by the Witt administration, including Witt’s own travel expenses.

Nothing of note was found, and on several occasions the I.G. proclaimed his

job done, only to be told to keep looking. Allbaugh launched his longest investigation

into a headdress that used to hang on James Lee Witt’s wall, a token of

appreciation from a Native American tribe in recognition of his efforts following

the Oklahoma City bombing. Someone said it might contain feathers from the protected

bald eagle—a federal offense—but the probe, which even involved

the F.B.I., fizzled when they turned out to be dyed chicken feathers.

With little understanding of or experience with large-scale disasters and little

patience with federal bureaucracies, Allbaugh was happy to go along with the

administration’s view of FEMA as a bloated entitlement program in need

of drastic cutbacks. “His position was that the states ought to take a

bigger role,” says Reid.

Flood mitigation, a high priority under Witt, received short shrift under Allbaugh.

The chief of mitigation, Anthony Lowe, was replaced with a veteran of the insurance

industry. Steve Kanstoroom, an independent fraud-detection and pattern-recognition

expert with 22 years’ experience, found that FEMA was allowing insurance

adjusters to use software that set artificially low settlement amounts for flood

victims, and that the claims-assessment process was deeply compromised by involvement

from insurance-industry figures.

At FEMA, as throughout the administration, the foxes had taken over the henhouse

and were partying up. Out the door, one by one, went the experienced disaster-relief

managers, and in came the political opportunists and the industry lobbyists.

“Many of their skilled management team has left,” says Kanstoroom.

“You’ve got a train running down the tracks with nobody driving

it.”

In retrospect, Allbaugh’s most damaging accomplishment at FEMA was pre-positioning

Michael Brown as his successor. Allbaugh included him in all key deliberations,

even naming him Chief Operating Officer, and Brown’s influence was apparent

to all. Within six months of Brown’s arrival as general counsel of FEMA,

Allbaugh was ready to promote him. First, though, he had to oust his current

acting deputy director, John Magaw—a former director of the U.S. Secret

Service and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, whom Clinton had placed

in charge of coordinating domestic-terrorism efforts for FEMA.

“One day, Mr. Allbaugh came in and said, ‘I know you’ve got

these other things to do. I’m going to ask Mr. Brown to be deputy,”

recalls Magaw, who promptly returned to the domestic-terror position assigned

him by Clinton. The timing was remarkable. Just a week prior to September 11,

2001, Allbaugh removed one of the most experienced men in government and replaced

him with one of the least experienced.

In December, with the country focused on terrorism and on preventing any more

attacks, Magaw left FEMA altogether, at the White House’s request, to

help start the Transportation Security Administration.

But before Brown could take over permanently as deputy director, he had to

face the Senate. In June 2002, he presented a résumé that was

riddled with exaggerations about his experience and serious omissions about

his financial and legal problems. One question on the disclosure form asks,

“Do you know why you were chosen for this nomination by the President?”

In a meandering written response, he wrote, in part: “I hope the President

has nominated me for the position of Deputy Director based on my commitment

to the agency and my ability to work closely with the Director.” Brown

was confirmed in a cakewalk.

Yet structural change at the agency was imminent. In the aftermath of 9/11,

with the public clamoring for coordinated anti-terror responses, it was evident

that FEMA could not remain independent. Bush, having initially opposed the creation

of a Department of Homeland Security, eventually caved to Congressional demands,

and Joe Allbaugh began to look for his exit strategy. The moment Homeland Security

swallowed FEMA, Allbaugh departed for the private sector, leaving Brown in charge.

Initially, FEMA staffers greeted Allbaugh’s hand-picked successor with

a sigh of relief. Brown was as outgoing as Allbaugh was introverted, as charming

as Allbaugh was gruff. On first meeting, people came away feeling like they’d

known him for a long time. “I was pretty impressed with him,” says

Trey Reid. “He was articulate, bright, a quick study. I didn’t have

to spend much time going over things with him.” On the personality front,

Brown was a vast improvement.

In terms of disaster-management, there were two eventualities FEMA lifers always

worried about: a really big California earthquake, and levee breaks in New Orleans.

But worrying and fixing were two different things. Brown, on the advice of aides,

asked for more money for levees and catastrophic planning, but neither Congress

nor the White House would bite.

If Allbaugh had been disinclined to press Bush for strong remedial action,

Brown lacked even the option. He didn’t really have a relationship with

the president, his diminutive nickname notwithstanding, and the Department of

Homeland Security was focused almost exclusively on terrorism. “I don’t

think any of the budget requests we submitted went through,” says Reid.

“Everything went for terrorism.”

With the defections of several senior managers and the firing of others, compounded

by the denial or reduction of budget requests, FEMA’s staff was left paper

thin. “At this point, there’s only one person in the building who

knows how to do certain things,” says Reid. “If that person gets

sick or dies, you’re shit out of luck.”

Despite all the cuts, however, there was always money for political purposes.

Ever mindful of avoiding his father’s mistakes—among them the disastrous

handling of Hurricane Andrew in 1992—Bush was not about to lose to John

Kerry over disaster relief. Under Brown, the response to a series of hurricanes

that battered Florida during the 2004 presidential campaign was as choreographed

as Bush’s landing on the U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln the previous year. Agency

staffers were everywhere, in FEMA T-shirts, and Brown was especially visible.

An investigation by the South Florida Sun-Sentinel later found that FEMA had

handed out tens of millions of dollars following Hurricane Frances to residents

and businesses in the Miami-Dade county area, where no deaths and only mild

damage occurred, while providing much less assistance to areas that were harder

hit but less politically crucial.

By August 2005, Brown was already rumored to be preparing his own exit into

the private sector. And just as Allbaugh had a reliable understudy in Brown,

Brown readied his own, elevating Patrick Rhode, a former Bush campaign advance

man who had become his chief of staff, to deputy director. While Rhode lacked

experience in emergency management, his public-relations and media skills had

been sharpened as a former television news anchor and reporter. Perhaps they’d

been sharpened a bit much: It was Rhode who, several days into the Katrina disaster,

would call FEMA’s performance “one of the most efficient and effective

responses in the country’s history.

CASHING IN

If being ostensibly “anti-government” while playing a leading role

in government is tricky, it all pays off on the back end. Nobody knows that

better than Allbaugh, whom Newsweek recently described as having “the

hide of a rhino” when it comes to criticism of conflicts of interest.

Once he left FEMA, he moved quickly to make up for years of privation in the

public sector, forming the Allbaugh Company with his wife, Diane, an attorney.

Diane Allbaugh had begun laying the groundwork from the moment they arrived

in Washington, D.C., repeating a pattern she’d established in Texas. In

the summer of 1996, just a year after moving to the Lone Star State, Diane had

signed on as a lobbyist with a number of large corporate clients, mostly energy

firms, with pressing business before the state, while her husband held a highly

visible position as the governor’s top aide. When the newspapers reported

the story, Governor Bush’s office hastened to announce new rules, and

Diane declared an end to her lobbying career. However, she was soon ensconced

in a ‘non-lobbying’ position with a law firm representing some of

the same companies. Now, in Washington, she jumped into the K Street fray, becoming

“of counsel” to Barbour, Griffith & Rogers, which Fortune magazine

described at the time as the country’s most powerful lobbying firm.

The shop’s founder, Haley Barbour, who would figure prominently in the

Allbaughs’ improving financial prospects, was the very definition of a

self-dealer. After founding the firm, he stayed involved with it while playing

a key role in the privatization of government services as chairman of the Republican

National Committee during Newt Gingrich’s “Contract with America”

revolution, then served as chairman of Bush’s 2000 presidential campaign

advisory committee. He left the company in 2003 to mount a successful run for

governor of Mississippi—where he ended up on television talking about

how his citizens were suffering from Katrina. No one thought to point out how

the Allbaugh-Brown-Barbour model of disaster management had set the stage for

the calamity.

A cynic (or a realist) might formulate that model like this: Why spend resources

to prevent disasters, when there’s so much money to be made cleaning up

after them?

Consider the trajectory of Shaw Group, a Baton Rouge engineering and construction

firm, and one of Allbaugh’s biggest clients. On August 15, 2005, with

hurricane season getting under way, Joe and Diane’s firm, Allbaugh Co.,

registered as a lobbyist for Shaw, which began advertising for workers to man

its rebuilding projects before Katrina even struck. After the levees broke,

Shaw, which had not been a FEMA contractor during the Clinton years, received

two separate $100 million federal clean-up contracts and saw its stock price

shoot up 50 percent in a few weeks. (After Brown departed FEMA, the agency announced

that it would re-bid some contracts that were given on a non-competitive basis,

including Shaw’s.)

Nevertheless, when the D.C. newspaper The Hill asked about the remarkable good

fortune of Allbaugh’s clients, his spokesperson, Patti Giglio, replied,

“The first thing he says when he sits down with a client is, ‘Don’t

hire me if you’re looking for a government contract.’

Maybe that’s why AshBritt Inc., didn’t hire Allbaugh. Instead,

the Florida-based environmental services firm hired Barbour Griffith—and

was selected by the Army Corps of Engineers to help lead the Katrina clean-up

effort. The contract, worth $568 million, was signed before the hurricane hit.

Interestingly, back in 2002, when an ice storm hit Allbaugh’s native Kay

County, Oklahoma, Allbaugh arranged a conference call with county officials,

who ended up choosing the Florida-based AshBritt over other firms with much

lower competing bids. (AshBritt has been much in the news in recent weeks, with

a plethora of pointed local articles raising questions about the company's operations,

its candor, and its spectacular growth during the Bush years — all through

its lucrative contracts to subcontract to other firms that do most of the actual

clean-up work.)

AshBritt’s president, Randal R. Perkins, said in an interview that he

did not recall the 2002 conference call, and noted that his firm doesn’t

deal directly with FEMA. “FEMA doesn’t contract directly, they just

pay the bills,” he said. As for Allbaugh, Perkins said, “I know

him, but I wouldn’t say that we are friends.”

Allbaugh’s web of self-interest ranges from disasters to energy to real

estate. And the self-serving links involve not just him, his wife, Brown, and

Barbour but also the vice president and the president. Haley Barbour advised

the Bush-Cheney campaign on strategy in 2000 while Joe Allbaugh was campaign

manager. During the transition, Allbaugh vetted Cheney’s qualifications

to be vice president.

After the election, Allbaugh served on Cheney’s secretive energy task

force while his wife was “of counsel” at the Barbour firm and being

paid as a “consultant” by Reliant Energy, Entergy, and Texas Utilities

Co. Diane Allbaugh says she did no lobbying. But Barbour, on behalf of an electricity-producing

client, successfully pushed Cheney’s task force to recommend that the

new administration renege on a campaign promise to limit carbon-dioxide emissions

from power plants. Bush, citing the task-force findings, complied.

The Allbaughs and Cheneys are literally so at home with each other that, on

first arriving in Washington in 2001, the Allbaughs bought Cheney’s townhouse

in McLean, Virginia, for $690,000. During the house tour, Cheney must have pointed

out the revolving doors. One of Allbaugh’s biggest clients is Cheney’s

former employer, Halliburton, whose Kellogg, Brown and Root subsidiary got at

least $61 million worth of Katrina business.

When Allbaugh left FEMA he did not, however, restrict himself to the domestic

disaster business. Instead, he cast a wider net into the entire Homeland Security/Defense

sector, thereby stressing his implied connections in the Department of Homeland

Security, which had absorbed FEMA, and in the Pentagon and White House. His

departure from government, in March, 2003, took place precisely as the invasion

of Iraq unfolded.

Allbaugh formed, with Barbour Griffith and numerous ex-officials of the Reagan

and Bush 41 administrations, a company called New Bridge Strategies. It moved

to secure contracts in Iraq the moment hostilities commenced. He also formed

Blackwell-Fairbanks, a joint venture with Andrew Lundquist, with whom he had

served on vice president Cheney’s secretive energy task force. (The name

of the company is based on the hometowns of the two principals.) Clients in

2004 included the aerospace giant Lockheed Martin; on required forms, Blackwell-Fairbanks

would later report that it had lobbied both the offices of the president and

of the vice president. Filings for Joe and Diane Allbaugh’s The Allbaugh

Company show among its clients Oshkosh Truck, the leading supplier of vehicles

to the Pentagon.

Now-Governor Barbour, who in early September dismissed criticism of the federal

Katrina response as “all cooked up by the news media and a few enemies

of George Bush,” declined a RealNews interview request.

history.

MURKY WATERS

Liz Roll / FEMA Photo Library

We may expect revelations in coming months and years about the process through

which FEMA awarded contracts. But it is likely that even the most cursory examination

will uncover high-level decisions that carried little obvious public benefit.

One such example might be the agency’s abrupt 2003 decision to award an

exclusive contract for water supplies in emergencies.

Prior to the Allbaugh-Brown reign, FEMA had handed out water contracts to a

variety of companies. One of the recipients, not surprisingly, was Nestle Waters

North America, easily the continent’s biggest producer, with 15 brands

of bottled water and 23 bottling facilities in the U.S. and Canada.

Then, without explanation, FEMA went sole-source, picking a little-known, family-run

firm called Lipsey Mountain Water. The company, based in Norcross, Georgia,

had just 15 full-time employees, no production capacity and no distribution

network. Instead, it was aggressively soliciting other companies to supply its

needs.

“The father and son came in and said, ‘We want you to sell us water,’”

recalls Kim Jeffery, president and C.E.O. of Nestle Waters North America. “I

said, ‘Why would I do that? I have a contract with FEMA.’ He said,

‘Because we have the contract now.’”

Lipsey trumpeted a sophisticated computer system that would supposedly ensure

speedy water deliveries and justify its exclusive five-year contract. But the

system did not work so well during the recent crisis, according to some in the

industry. Joe Doss, president of the trade group for water suppliers, says his

members were besieged with reports of delays in water deliveries after the hurricane,

and that within one 24-hour period they voluntarily trucked in 1.5 million bottles.

(And again, when Hurricane Wilma swept through Florida in late October, distribution

sites turned people away without water days after the event.)

Lipsey Mountain Water may be new to the world of federal water contracts, but

its principals are not new to politics. The Lipseys are part of a politically

connected family that gives regularly to both political parties and owns one

of the country’s largest gun wholesalers. The gun lobby is still the nation's

most powerful, as acknowledged by Dick Cheney, who addressed the National Rifle

Association’s 2004 annual meeting and noted from the podium: “I’m…delighted

to see my good friend, former director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency,

Joe Allbaugh. Joe is here this evening. It’s always good to have a firearm

if you get into real trouble—but the next best thing is Joe Allbaugh.”

In November, the Pentagon confirmed that its inspector general was investigating

Lipsey in response to complaints received by Congress from truck drivers, trucking

brokers and ice producers who did much of the actual work under Lipsey's contract

and say Lipsey has not paid their bills or even answered their phone calls.

(Company president Joe Lipsey III did not respond to a list of questions he

had requested from RealNews.)

Only through the painstaking unraveling of connections like these are we likely

to grasp the truth about the secretive conflicts of interest that waste billions

of public dollars and undermine the country’s readiness to respond to

natural and man-made disasters.. Such inquiries are not welcome, of course.

Instead, we are all supposed to play Sgt. Schultz, and "see nuuussing."

The Administration's motto might easily be "Nothing to see here, folks,

move along quickly, please."

Indeed, when a National Public Radio interviewer posed questions about the

handling of the storm to Vice Admiral Thad Allen, whom President Bush had assigned

to take over the Katrina response from Michael Brown, Allen said that there

was no point in dwelling on the past. “I would say that the longer the

discourse continues about what might or might not have happened and the political

issues surrounding that—I think at some point it starts to devalue the

work of a whole lot of FEMA workers out there that are working very, very hard

for the American public.’

Yet no one devalued the work of the rank and file of FEMA workers more than

the Joe Allbaugh, Michael Brown, and their boss. And the discourse the administration

wished to avoid was, and is, urgently needed.

Today, FEMA's front line troops struggle with the legacy of Katrina, overwhelming

challenges and devastated morale. Meanwhile, Joe Allbaugh travels the world,

soliciting business, and even the disgraced Brown has announced his move into

the consulting business. President Bush has thus far not had to explain anything

– and the White House has declined to turn over to Congress key documents

about Hurricane Katrina or to make senior officials available for sworn testimony.

Russ Baker, founder of the Real News Project and author

of this article, is a longtime, award-winning investigative journalist and essayist.

His work has appeared in many of the world’s finest news outlets. The

Real News Project is a new organization dedicated to producing groundbreaking

investigative reporting on the big stories of our time.