Untitled Document

|

|

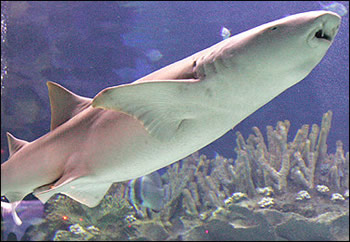

A nurse shark at an aquarium. The Pentagon is reportedly funding research into neural implants with the ultimate hope of turning sharks into "stealth spies" capable of gliding undetected through the ocean(AFP/File)

|

Military scientists in the United States are developing a way of manipulating

sharks by remote control to turn them into underwater spies or weapons.

Engineers funded by the Pentagon have created electronic brain implants for

fish that they hope will be able to influence the movements of sharks and perhaps

even decode what they are sensing.

Although both Cold War superpowers have trained sea mammals such as dolphins

and killer whales to carry out quasi-military duties, this is probably the first

time the military have seriously considered using fish.

The Pentagon hopes to exploit the ability of sharks to glide quietly through

the water, sense delicate electrical gradients and follow chemical trails, according

to New Scientist magazine.

"These researchers hope such implants will improve our understanding of

how the animals interact with their environment, as well as boosting research

into tackling human paralysis," says New Scientist.

But the research also has a military objective. "By remotely guiding sharks'

movements, they hope to transform the animals into stealth spies, perhaps capable

of following vessels without being spotted," the magazine says.

The neural implants consist of electrodes buried in the fish's brain which

can then be triggered by remote control to stimulate specific areas of the animal's

central nervous system.

New Scientist says that the project is funded by the US Defence Advanced Research

Projects Agency in Arlington, Virginia, which is also involved in a number of

other research studies investigating the use of electronic implants to monitor

or control the movements or behaviour of animals.

Scientists at Boston University have already developed brain implants that

can influence the movements of dogfish - members of the shark family - by "steering"

them with a phantom odour.

The electrodes are attached to the region of the dogfish brain associated with

scent detection. When the stimulus is to the right side of the olfactory centre

the fish turn right, when it is left, the fish swim left.

The stronger the signal, the more sharply it turns.

The shark study is also designed to investigate the possibility of monitoring

the brain activity of a shark to decipher different patterns of activity that

indicate whether the fish has detected an ocean current, a scent or an electrical

field.