Untitled Document

|

|

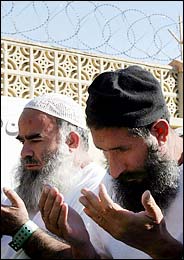

Afghans prayed after their release from the Bagram detention center near Kabul earlier this month. Syed Jan Sabawoon/European Pressphoto Agency

|

While an international debate rages over the future of the American

detention center at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, the military has quietly expanded

another, less-visible prison in Afghanistan, where it now holds some 500 terror

suspects in more primitive conditions, indefinitely and without charges.

Pentagon officials have often described the detention site at Bagram, a cavernous

former machine shop on an American air base 40 miles north of Kabul, as a screening

center. They said most of the detainees were Afghans who might eventually be

released under an amnesty program or transferred to an Afghan prison that is

to be built with American aid.

But some of the detainees have already been held at Bagram for as long as two

or three years. And unlike those at Guantánamo, they have no access to

lawyers, no right to hear the allegations against them and only rudimentary

reviews of their status as "enemy combatants," military officials

said.

Privately, some administration officials acknowledge that the situation at

Bagram has increasingly come to resemble the legal void that led to a landmark

Supreme Court ruling in June 2004 affirming the right of prisoners at Guantánamo

to challenge their detention in United States courts.

While Guantánamo offers carefully scripted tours for members of Congress

and journalists, Bagram has operated in rigorous secrecy since it opened in

2002. It bars outside visitors except for the International Red Cross and refuses

to make public the names of those held there. The prison may not be photographed,

even from a distance.

From the accounts of former detainees, military officials and soldiers who

served there, a picture emerges of a place that is in many ways rougher and

more bleak than its counterpart in Cuba. Men are held by the dozen in large

wire cages, the detainees and military sources said, sleeping on the floor on

foam mats and, until about a year ago, often using plastic buckets for latrines.

Before recent renovations, they rarely saw daylight except for brief visits

to a small exercise yard.

"Bagram was never meant to be a long-term facility, and now it's a long-term

facility without the money or resources," said one Defense Department official

who has toured the detention center. Comparing the prison with Guantánamo,

the official added, "Anyone who has been to Bagram would tell you it's

worse."

Former detainees said the renovations had improved conditions somewhat, and

human rights groups said reports of abuse had steadily declined there since

2003. Nonetheless, the Pentagon's chief adviser on detainee issues, Charles

D. Stimson, declined to be interviewed on Bagram, as did senior detention officials

at the United States Central Command, which oversees military operations in

Afghanistan.

The military's chief spokesman in Afghanistan, Col. James R. Yonts, also refused

to discuss detainee conditions, other than to say repeatedly that his command

was "committed to treating detainees humanely, and providing the best possible

living conditions and medical care in accordance with the principles of the

Geneva Convention."

Other military and administration officials said the growing detainee population

at Bagram, which rose from about 100 prisoners at the start of 2004 to as many

as 600 at times last year, according to military figures, was in part a result

of a Bush administration decision to shut off the flow of detainees into Guantánamo

after the Supreme Court ruled that those prisoners had some basic due-process

rights. The question of whether those same rights apply to detainees in Bagram

has not been tested in court.

Until the court ruling, Bagram functioned as a central clearing house for the

global fight against terror. Military and intelligence personnel there sifted

through captured Afghan rebels and suspected terrorists seized in Afghanistan,

Pakistan and elsewhere, sending the most valuable and dangerous to Guantánamo

for extensive interrogation, and generally releasing the rest.

But according to interviews with current and former administration officials,

the National Security Council effectively halted the movement of new detainees

into Guantánamo at a cabinet-level meeting at the White House on Sept.

14, 2004.

Wary of further angering Guantánamo's critics, the council authorized

a final shipment of 10 detainees eight days later from Bagram, the officials

said. But it also indicated that it wanted to review and approve any Defense

Department proposals for further transfers. Despite repeated requests from military

officials in Afghanistan and one formal recommendation by a Pentagon working

group, no such proposals have been considered, officials said.

"Guantánamo was a lightning rod," said a former senior administration

official who participated in the discussions and who, like many of those interviewed,

would discuss the matter in detail only on the condition of anonymity because

of the secrecy surrounding it. "For some reason, people did not have a

problem with Bagram. It was in Afghanistan."

Yet Bagram's expansion, which was largely fueled by growing numbers of detainees

seized on the battlefield and a bureaucratic backlog in releasing many of the

Afghan prisoners, also underscores the Bush administration's continuing inability

to resolve where and how it will hold more valuable terror suspects.

Military officials with access to intelligence reporting on the subject said

about 40 of Bagram's prisoners were Pakistanis, Arabs and other foreigners;

some were previously held by the C.I.A. in secret interrogation centers in Afghanistan

and other countries. Officials said the intelligence agency had been reluctant

to send some of those prisoners on to Guantánamo because of the possibility

that their C.I.A. custody could eventually be scrutinized in court.

Defense Department officials said the C.I.A.'s effort to unload some detainees

from its so-called black sites had provoked tension among some officials at

the Pentagon, who have frequently objected to taking responsibility for terror

suspects cast off by the intelligence agency. The Defense Department "doesn't

want to be the dumping ground," one senior official familiar with the interagency

debates said. "There just aren't any good options."

A spokesman for the Central Intelligence Agency declined to comment.

Conditions at Bagram

The rising number of detainees at Bagram has been noted periodically by the

military and documented by the International Committee of the Red Cross, which

does not make public other aspects of its findings. But because the military

does not identify the prisoners or release other information on their detention,

it had not previously been clear that some detainees were being held there for

such long periods.

The prison rolls would be even higher, officials noted, were it not for a Pentagon

decision in early 2005 to delegate the authority to release them from the deputy

secretary of defense to the military's Central Command, which oversees the 19,000

American troops in Afghanistan, and to the ground commander there.

Since January 2005, military commanders in Afghanistan have released about

350 detainees from Bagram in conjunction with an Afghan national reconciliation

program, officials said. Even so, one Pentagon official said the current average

stay of prisoners at Bagram was 14.5 months.

Officials said most of the current Bagram detainees were captured during American

military operations in Afghanistan, primarily in the country's restive south,

beginning in the spring of 2004.

"We ran a couple of large-scale operations in the spring of 2004, during

which we captured a large number of enemy combatants," said Maj. Gen. Eric

T. Olson, who was the ground commander for American troops in Afghanistan at

the time. In subsequent remarks he added, "Our system for releasing detainees

whose intelligence value turned out to be negligible did not keep pace with

the numbers we were bringing in."

General Olson and other military officials said the growth at Bagram had also

been a consequence of the closing of a smaller detention center at Kandahar

and efforts by the military around the same time to move detainees more quickly

out of "forward operating bases," in the Afghan provinces, where international

human rights groups had cited widespread abuses.

At Bagram, reports of abuses have markedly declined since the violent deaths

of two Afghan men held there in December 2002, Afghan and foreign human rights

officials said.

After an Army investigation, the practices found to have caused those two deaths

— the chaining of detainees by the arms to the ceilings of their cells

and the use of knee strikes to the legs of disobedient prisoners by guards —

were halted by early 2003. Other abusive methods, like the use of barking attack

dogs to frighten new prisoners and the handcuffing of detainees to cell doors

to punish them for talking, were phased out more gradually, military officials

and former detainees said.

Human rights officials and former detainees said living conditions at the detention

center had also improved.

Faced with serious overcrowding in 2004, the military initially built some

temporary prison quarters and began refurbishing the main prison building at

Bagram, a former aircraft-machine shop built by Soviet troops during their occupation

of the country in the 1980's.

Corrals surrounded by stacked razor wire that had served as general-population

cells gave way to less-forbidding wire pens that generally hold no more than

15 detainees, military officials said. The cut-off metal drums used as toilets

were eventually replaced with flush toilets.

Last March, a nine-bed infirmary opened, and months later a new wing was built.

The expansion brought improved conditions for the more than 250 prisoners who

have been housed there, officials said.

Still, even the Afghan villagers released from Bagram over the past year tend

to describe it as a stark, forsaken place.

"It was like a cage," said one former detainee, Hajji Lalai Mama,

a 60-year-old tribal elder from the Spinbaldak district of southern Afghanistan

who was released last June after nearly two years. Referring to a zoo in Pakistan,

he added, "Like the cages in Karachi where they put animals: it was like

that."

Guantánamo, which once kept detainees in wire-mesh cages, now houses

them in an elaborate complex of concrete and steel buildings with a hospital,

recreation yards and isolation areas. At Bagram, detainees are stripped on arrival

and given orange uniforms to wear. They wash in collective showers and live

under bright indoor lighting that is dimmed for only a few hours at night.

Abdul Nabi, a 24-year-old mechanic released on Dec. 15 after nine months, said

some detainees frequently protested the conditions, banging on their cages and

sometimes refusing to eat. He added that infractions of the rules were dealt

with unsparingly: hours handcuffed in a smaller cell for minor offenses, and

days in isolation for repeated transgressions.

"We were not allowed to talk very much," he said in an interview.

The Rights of Detainees

The most basic complaint of those released was that they had been wrongly detained

in the first place. In many cases, former prisoners said they had been denounced

by village enemies or arrested by the local police after demanding bribes they

could not pay.

Human rights lawyers generally contend that the Supreme Court decision on Guantánamo,

in the case of Rasul v. Bush, could also apply to detainees at Bagram. But lawyers

working on behalf of the Guantánamo detainees have been reluctant to

take cases from Bagram while the reach of the Supreme Court ruling, which is

now the subject of further litigation, remains uncertain.

As at Guantánamo, the military has instituted procedures at Bagram intended

to ensure that the detainees are in fact enemy combatants. Yet the review boards

at Bagram give fewer rights to the prisoners than those used in Cuba, which

have been criticized by human rights officials as kangaroo courts.

The two sets of panels that review the status of detainees at Guantánamo

assign military advocates to work with detainees in preparing cases. Detainees

are allowed to hear and respond to the allegations against them, call witnesses

and request evidence. Only a small fraction of the hundreds of panels have concluded

that the accused should be released.

The Bagram panels, called Enemy Combatant Review Boards, offer no such guarantees.

Reviews are conducted after 90 days and at least annually thereafter, but detainees

are not informed of the accusations against them, have no advocate and cannot

appear before the board, officials said. "The detainee is not involved

at all," one official familiar with the process said.

An official of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission, Shamsullah Ahmadzai,

noted that the Afghan police, prosecutors and the courts were all limited by

law in how long they could hold criminal suspects.

"The Americans are detaining people without any legal procedures,"

Mr. Ahmadzai said in an interview in Kabul. "Prisoners do not have the

opportunity to demonstrate their innocence."

Under a diplomatic arrangement reached last year after more than a year of

negotiations, Afghan officials have agreed to take over custody of the roughly

450 Afghan detainees now at Bagram and another 100 Afghans held at Guantánamo

once American-financed contractors refurbish a block of a decrepit former Soviet

jail near Kabul as a high-security prison.

Because of the $10 million prison- construction project and an accompanying

American program to train Afghan prison guards, both of which are to be completed

in about a year, military officials in the region have abandoned any thought

of sending any of the Afghan detainees at Bagram to Guantánamo. Still,

many details of the deal remain uncertain, including when the new prison will

be completed, which Afghan ministry will run it and how the detainees may be

prosecuted in Afghan courts.

Pentagon officials said some part of the Bagram prison would probably continue

to operate, holding the roughly 40 non-Afghan detainees there as well as others

likely to be captured by American or NATO forces in continuing operations.

Prisoner Transfers Stalled

Until now, military officials at both Bagram and Guantánamo have been

frustrated in their efforts to engineer the transfer to Cuba of another group

of the most dangerous and valuable non-Afghan detainees held at Bagram, Pentagon

officials said.

Three officials said commanders at Bagram first proposed moving about a dozen

detainees to Guantánamo in late 2004 and then reiterated the request

in early 2005. In an unusual step last spring, the officials added, intelligence

specialists based at Guantánamo traveled to Bagram to assess the need

for the transfer.

But as Central Command officials were forwarding a formal request to the Pentagon

for the transfer of about a dozen high-level detainees, at least one of them,

Omar al-Faruq, a former operative of Al Qaeda in Southeast Asia, escaped from

the Bagram prison with three other men. Mr. Faruq had first been taken to Bagram

by C.I.A. operatives in late summer 2002, but was removed from the prison about

a month later, a soldier who served there said.

Two officials familiar with intelligence reports on the escape said that last

July, after Mr. Faruq had been returned to Bagram by the C.I.A., he and the

other men slipped out of a poorly fenced-in cell and, in the middle of the night,

piled up some boxes and climbed through an open transom over one of the doors.

In August, weeks after the escape, a Defense Department working group called

the Detainee Assistance Team endorsed the Central Command's recommendation for

the transfer of nine Bagram detainees to Guantánamo, two officials familiar

with the matter said.

Since then, the recommendation has languished in the Pentagon bureaucracy.

Officials said it had apparently been stalled by aides who had declined to forward

it to Secretary of Defense Donald

H. Rumsfeld out of concern that any new transfers to Guantánamo would

stoke international criticism.

"Out of sight, out of mind," one of those officials said of the Bagram

detainees.

Carlotta Gall, Ruhullah Khapalwak and Abdul

Waheed Wafa contributed reporting from Afghanistan for this article.