Untitled Document

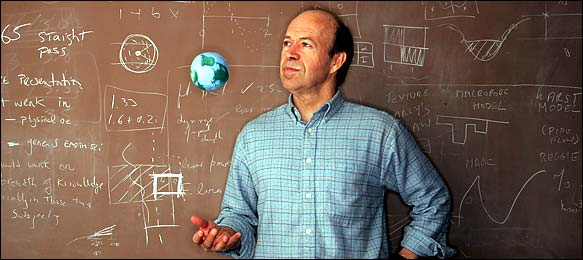

James E. Hansen, top NASA climate scientist, on Friday at the Goddard Institute in Upper Manhattan. Fred R. Conrad/The New York Times

The top climate scientist at NASA says the Bush administration has

tried to stop him from speaking out since he gave a lecture last month calling

for prompt reductions in emissions of greenhouse gases linked to global warming.

The scientist, James E. Hansen, longtime director of the agency's Goddard Institute

for Space Studies, said in an interview that officials at NASA headquarters

had ordered the public affairs staff to review his coming lectures, papers,

postings on the Goddard Web site and requests for interviews from journalists.

Dr. Hansen said he would ignore the restrictions. "They feel their job

is to be this censor of information going out to the public," he said.

Dean Acosta, deputy assistant administrator for public affairs at the space

agency, said there was no effort to silence Dr. Hansen. "That's not the

way we operate here at NASA," Mr. Acosta said. "We promote openness

and we speak with the facts."

He said the restrictions on Dr. Hansen applied to all National Aeronautics

and Space Administration personnel. He added that government scientists were

free to discuss scientific findings, but that policy statements should be left

to policy makers and appointed spokesmen.

Mr. Acosta said other reasons for requiring press officers to review interview

requests were to have an orderly flow of information out of a sprawling agency

and to avoid surprises. "This is not about any individual or any issue

like global warming," he said. "It's about coordination."

Dr. Hansen strongly disagreed with this characterization, saying such procedures

had already prevented the public from fully grasping recent findings about climate

change that point to risks ahead.

"Communicating with the public seems to be essential," he said, "because

public concern is probably the only thing capable of overcoming the special

interests that have obfuscated the topic."

Dr. Hansen, 63, a physicist who joined the space agency in 1967, directs efforts

to simulate the global climate on computers at the Goddard Institute in Morningside

Heights in Manhattan.

Since 1988, he has been issuing public warnings about the long-term threat

from heat-trapping emissions, dominated by carbon dioxide, that are an unavoidable

byproduct of burning coal, oil and other fossil fuels. He has had run-ins with

politicians or their appointees in various administrations, including budget

watchers in the first Bush administration and Vice President Al Gore.

In 2001, Dr. Hansen was invited twice to brief Vice President Dick Cheney and

other cabinet members on climate change. White House officials were interested

in his findings showing that cleaning up soot, which also warms the atmosphere,

was an effective and far easier first step than curbing carbon dioxide.

He fell out of favor with the White House in 2004 after giving a speech at

the University of Iowa before the presidential election, in which he complained

that government climate scientists were being muzzled and said he planned to

vote for Senator John Kerry.

But Dr. Hansen said that nothing in 30 years equaled the push made since early

December to keep him from publicly discussing what he says are clear-cut dangers

from further delay in curbing carbon dioxide.

In several interviews with The New York Times in recent days, Dr. Hansen said

it would be irresponsible not to speak out, particularly because NASA's mission

statement includes the phrase "to understand and protect our home planet."

He said he was particularly incensed that the directives had come through telephone

conversations and not through formal channels, leaving no significant trails

of documents.

Dr. Hansen's supervisor, Franco Einaudi, said there had been no official "order

or pressure to say shut Jim up." But Dr. Einaudi added, "That doesn't

mean I like this kind of pressure being applied."

The fresh efforts to quiet him, Dr. Hansen said, began in a series of calls

after a lecture he gave on Dec. 6 at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical

Union in San Francisco. In the talk, he said that significant emission cuts

could be achieved with existing technologies, particularly in the case of motor

vehicles, and that without leadership by the United States, climate change would

eventually leave the earth "a different planet."

The administration's policy is to use voluntary measures to slow, but not reverse,

the growth of emissions.

After that speech and the release of data by Dr. Hansen on Dec. 15 showing

that 2005 was probably the warmest year in at least a century, officials at

the headquarters of the space agency repeatedly phoned public affairs officers,

who relayed the warning to Dr. Hansen that there would be "dire consequences"

if such statements continued, those officers and Dr. Hansen said in interviews.

Among the restrictions, according to Dr. Hansen and an internal draft memorandum

he provided to The Times, was that his supervisors could stand in for him in

any news media interviews.

Mr. Acosta said the calls and meetings with Goddard press officers were not

to introduce restrictions, but to review existing rules. He said Dr. Hansen

had continued to speak frequently with the news media.

But Dr. Hansen and some of his colleagues said interviews were canceled as

a result.

In one call, George Deutsch, a recently appointed public affairs officer at

NASA headquarters, rejected a request from a producer at National Public Radio

to interview Dr. Hansen, said Leslie McCarthy, a public affairs officer responsible

for the Goddard Institute.

Citing handwritten notes taken during the conversation, Ms. McCarthy said Mr.

Deutsch called N.P.R. "the most liberal" media outlet in the country.

She said that in that call and others, Mr. Deutsch said his job was "to

make the president look good" and that as a White House appointee that

might be Mr. Deutsch's priority.

But she added: "I'm a career civil servant and Jim Hansen is a scientist.

That's not our job. That's not our mission. The inference was that Hansen was

disloyal."

Normally, Ms. McCarthy would not be free to describe such conversations to

the news media, but she agreed to an interview after Mr. Acosta, at NASA headquarters,

told The Times that she would not face any retribution for doing so.

Mr. Acosta, Mr. Deutsch's supervisor, said that when Mr. Deutsch was asked

about the conversations, he flatly denied saying anything of the sort. Mr. Deutsch

referred all interview requests to Mr. Acosta.

Ms. McCarthy, when told of the response, said: "Why am I going to go out

of my way to make this up and back up Jim Hansen? I don't have a dog in this

race. And what does Hansen have to gain?"

Mr. Acosta said that for the moment he had no way of judging who was telling

the truth. Several colleagues of both Ms. McCarthy and Dr. Hansen said Ms. McCarthy's

statements were consistent with what she told them when the conversations occurred.

"He's not trying to create a war over this," said Larry D. Travis,

an astronomer who is Dr. Hansen's deputy at Goddard, "but really feels

very strongly that this is an obligation we have as federal scientists, to inform

the public."

Dr. Travis said he walked into Ms. McCarthy's office in mid-December at the

end of one of the calls from Mr. Deutsch demanding that Dr. Hansen be better

controlled.

In an interview on Friday, Ralph J. Cicerone, an atmospheric chemist and the

president of the National Academy of Sciences, the nation's leading independent

scientific body, praised Dr. Hansen's scientific contributions and said he had

always seemed to describe his public statements clearly as his personal views.

"He really is one of the most productive and creative scientists in the

world," Dr. Cicerone said. "I've heard Hansen speak many times and

I've read many of his papers, starting in the late 70's. Every single time,

in writing or when I've heard him speak, he's always clear that he's speaking

for himself, not for NASA or the administration, whichever administration it's

been."

The fight between Dr. Hansen and administration officials echoes other recent

disputes. At climate laboratories of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration,

for example, many scientists who routinely took calls from reporters five years

ago can now do so only if the interview is approved by administration officials

in Washington, and then only if a public affairs officer is present or on the

phone.

Where scientists' points of view on climate policy align with those of the

administration, however, there are few signs of restrictions on extracurricular

lectures or writing.

One example is Indur M. Goklany, assistant director of science and technology

policy in the policy office of the Interior Department. For years, Dr. Goklany,

an electrical engineer by training, has written in papers and books that it

may be better not to force cuts in greenhouse gases because the added prosperity

from unfettered economic activity would allow countries to exploit benefits

of warming and adapt to problems.

In an e-mail exchange on Friday, Dr. Goklany said that in the Clinton administration

he was shifted to nonclimate-related work, but added that he had never had to

stop his outside writing, as long as he identified the views as his own.

"One reason why I still continue to do the extracurricular stuff,"

he wrote, "is because one doesn't have to get clearance for what I plan

on saying or writing."