Untitled Document

|

|

A woman from Odioma and her sick child traveled to a distant town for care because Odioma has no medical facilities. The area is oil rich but both villages are poor. Michael Kamber for The New York Times

|

At first glance, it is hard to imagine anyone fighting over this place.

Approached by a creek, the only way to get here, a day's journey by dugout

canoe from the nearest town, it presents itself as a collection of battered

shacks teetering on a steadily eroding beach.

On Sunday morning, the village children shimmy out of their best clothes after

church and head to a muddy puddle to collect water. Their mothers use the murky

liquid to cook whatever soup they can muster from the meager catch of the day.

Yet for months a pitched battle has been fought between communities that claim

authority over this village and the right to control what lies beneath its watery

ground: a potentially vast field of crude oil that has caught the attention

of a major energy company.

The conflict has left dozens dead and wounded, sent hundreds fleeing their

homes and roiled this once quiet part of the Niger Delta. It has also laid bare

the desperate struggle of impoverished communities to reap crumbs from the lavish

banquet the oil boom has laid in this oil-rich yet grindingly poor corner of

the globe.

"This region is synonymous with oil, but also with unbelievable poverty,"

said Anyakwee Nsirimovu, executive director of Institute of Human Rights and

Humanitarian Law in the Niger Delta. That combination is an inevitable recipe

for bloodshed and misery, he said. "The world depends on their oil, but

for the people of the Niger Delta oil is more of a curse than a blessing."

Africa is in the midst of an oil boom, with companies and governments

pouring $50 billion into projects that may double the continent's oil output

in the next decade.

In the world's thirst for oil and the United States' efforts to obtain

it outside the troubled Middle East, African oil has become essential. Africa

is expected to provide the United States with a quarter of its oil supply in

the next decade, compared with about 15 percent now, and much of it will come

from the Gulf of Guinea, where the Niger Delta sits.

|

|

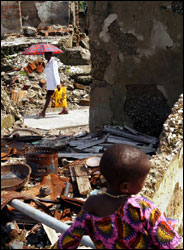

Odioma, a Nigerian village, was damaged by the army last year in a dispute over oil rights, residents said.

Michael Kamber for The New York Times

|

But much of that oil will come from places like Obioku, and with it a tangled

and often bloody web of conflict marked by poverty and a near abdication of

responsibility by government.

Even though Nigeria elected a democratic government in 1999, which raised hopes

for the long-suffering delta region, almost none of the enormous wealth the

oil creates reaches places like this. The isolation of Obioku is total. With

no fast boats available, the nearest health center or clinic is a day's journey

away. No telephone service exists here. Radio brings the only news of the world

outside. Nothing hints that the people here live in a nation enjoying the profits

of record-high oil prices.

"It is like we don't exist, as far as government is concerned," said

Worikuma Idaulambo, chairman of Obioku's council of chiefs.

Nigeria is a longstanding OPEC member that exported nearly $30 billion of oil

in 2004, the United States Department of Energy said. Nigeria sends 13 percent

of revenues from its states back, a hefty sum for the underdeveloped ones where

oil is produced. Much of that is siphoned off by corrupt regional officials

who often pocket the money or waste it on lavish projects that do little, if

anything, for ordinary people.

A result has been a violent struggle over the jobs, schools and other aid that

oil companies have offered to encourage local residents to cooperate. Here in

Obioku, as in many towns in the delta, an oil company, in this case a subsidiary

of Royal Dutch Shell, has brought the only signs of modernity. In 1998, Shell

bought the rights to drill for oil near a small fishing settlement at the edge

of Obioku, no more than a handful of rough shelters made of grass and wood.

|

|

Royal Dutch Shell's oil plant in Bonny, Nigeria. Shell bought oil drilling rights near a fishing settlement at the edge of Obioku, an isolated village, and agreed to help develop it.

Michael Kamber for The New York Times

|

Shell signed agreements with the chiefs of Obioku and with leaders in the nearest

town, Nembe-Bassambiri, to help develop Obioku. In time, Shell built a water

tower, gave the village a generator and built a primary school. In return, the

village agreed to allow Shell and its contractors to work freely.

For years Shell did nothing with the field. Then, early last year, a Shell

contractor arrived to begin work, and trouble started.

Officials in a nearby town, Odioma, laid claim to the land, and demanded that

the oil company pay tribute if it wanted to drill.

"This is Odioma land," said Daniel I. L. Orumiegha-Bari, a member

of Odioma's council of chiefs. "It belongs to us. Anyone claiming otherwise

is an interloper wanting to revise hundreds of years of our history."

Chiefs in Nembe-Bassambiri, who were receiving payments on the premise that

the land was theirs, rejected Odioma's claim.

Human rights and environmental groups have long criticized the practices of

Shell, the oldest and largest of Nigeria's oil producers. As a result of a stinging

internal report in 2003 that said Shell, whether intentionally or not, "creates,

feeds into or exacerbates conflict," the company revamped its community

relations strategy. Shell immediately withdrew from the Obioku area and referred

the dispute to local government authorities to resolve.

In this serpentine labyrinth of rivers and creeks, where fishermen eke out

a living casting homemade nets, who owned Obioku was academic to the chiefs

of Odioma and Nembe-Bassambiri until Shell arrived. But with the sudden promise

of payment, the dispute escalated, first in increasingly belligerent letters

among the three villages.

Words soon gave way to action, and blood began to flow into the rivers and

creeks. In February, a boat filled with local government councilors on a mission

to broker a deal among the feuding communities was attacked, and a dozen people

were killed.

Officials in Nembe-Bassambiri blamed a militant youth group in Odioma for the

slaughter. The group is believed to be involved in bunkering: stealing oil by

breaking into pipelines.

|

|

Children drew water from a muddy pool, the only source of water for Obioku.

Michael Kamber for The New York Times

|

As is common here, group members had been hired by an oil company contractor

to provide security on the waterways, chiefs in Odioma and other villages said.

Such contracts are often a way to buy cooperation from youths who would otherwise

attack oil installations and harass workers.

Contending that it sought to arrest the members of the youth group, a unit

of the Nigerian military known as the Joint Task Force, charged with security

in the Niger Delta, went to Odioma on Feb. 19.

Thinking that the task force was coming to help them, Odioma's chiefs had gathered

in the village king's palace to receive it. But shots were fired, and the chiefs

scattered.

"We thought they came in peace," said Mr. Orumiegha-Bari, the Odioma

chief. "But they destroyed our village."

The army flattened Odioma, residents said, leaving behind a barren moonscape

covered with a carpet of ash, broken glass and burned concrete where an idyllic

village once stood. At least 17 people died in the raid, including a 12-year-old

boy called Lucky, Mr. Orumiegha-Bari said.

Ayebatari Silgbanibo had been sitting in the tiny office of his computer business,

which he started with a grant from Shell, when the gunfire started. "I

didn't want to leave my computer because it is all I have," Mr. Silgbanibo,

22, said. "But I was afraid."

When he returned, his computer and printer had been destroyed. He is a fisherman

now, like his father and most of the men in this village, earning about a dollar

a day. The computer, which he received because Odioma has its own oil wells,

apart from Obioku, was supposed to lift him out of generations of poverty.

"How can I ever buy a new computer?" he said. "It is impossible."

Brig. Gen. Elias Zamani, commander of the Joint Task Force, said his soldiers

opened fire on Odioma only after being fired upon. "They were lying in

wait for the arrival of our troops," he said of the youth group.

He said some houses had been destroyed when stray bullets struck buildings

where petroleum was stored. The army disputes the death toll, saying army officials

asked to see bodies and graves and could not find any. But a report on the attack

by Amnesty International in November concluded that the destruction seemed to

have had specific targets, destroying the houses of the village king and other

officials.

And yet, Mr. Orumiegha-Bari said he was grateful that it was the Joint Task

Force that had attacked his village and not their neighbors in Nembe-Bassambiri.

"If Bassambiri people came first you wouldn't have seen anybody here to

talk to," the chief said. "They would have slaughtered every last

man."

The village has asked the army to stay to protect residents from their neighbors.

"We don't like that they are here, but it is better that they stay,"

Mr. Orumiegha-Bari said. The arrival of the soldiers, village leaders said,

is the first time any federal government representative has had a presence in

Odioma.

It is hard to say who is to blame for the violence that has wracked this pocket

of Nigeria. Some villagers and human rights groups blame the oil companies and

their contractors, which pay for economic development and employ youths, creating

an incentive for communal violence. Still others blame the federal, state and

local governments, which collect and distribute millions of dollars in the names

of local residents yet never seem to produce much benefit.

"These conflicts are a direct result of the abandonment of these communities

by their government," Mr. Nsirimovu said. "If their government took

care of them they wouldn't be fighting over these little scraps and rewards

from the oil companies."

Federal officials acknowledge that corruption is a big problem but point out

that even if Nigeria is having an oil boom, it does not amount to great wealth

per capita. In 2004, after costs were deducted, Nigeria's oil money amounted

about 50 cents per day for each of the country's 130 million people, they said.

Shell officials defended their role in the crisis, saying they withdrew from

the area as soon as a conflict over ownership arose. They said it was primarily

the job of Nigeria's elected officials to develop the country, but added that

in addition to taxes and royalties, they contributed 3 percent of their annual

operating budget to a fund to help develop the delta. In 2004, the company's

contribution to that fund was nearly $70 million.

"Government is so removed that they see the oil companies as being the

nearest government to them," said Don S. Bonham, a spokesman for Shell

in the oil capital of Port Harcourt. "The expectations of government have

not been met."

The communities fighting over the oil fields are in Bayelsa State, which produces

a third of Nigeria's oil and has an annual budget of more than half a billion

dollars to spend on its three million people. But most of it goes to white elephants

like a mansion for the governor and his deputy.

"This is what we eat," said Paulgba Tekikuma, an Obioku resident,

gesturing to a small bowl half-full of tiny fish and crustaceans she would mix

with milled cassava. "The water, sometimes it get the babies sick when

they drink. But we no get any other."

Corruption is largely to blame. The state's governor, Diepreye Alamieyeseigha,

was arrested in London on money laundering charges in September, then fled to

Nigeria, where he enjoyed immunity even from prosecutors, in November. He is

suspected of stealing hundreds of millions of dollars from the state since he

was elected in 1999. He has since been impeached, and as a result charged with

corruption and money laundering in Nigeria. After an inquiry in 2005, Amnesty

International concluded, "As with many violent disputes within communities

in the Niger Delta, access to oil resources is at the root of the Odioma incident."

Mr. Nsirimovu, the human rights advocate, said the underdevelopment of the

region both caused and exacerbated the violence. Until real development begins,

"blood will flow freely in the Niger Delta," he said. "Mark my

words."