Untitled Document

|

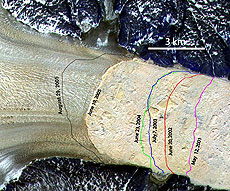

Lines on this satellite image

of Greenland's Helheim glacier show the positions of the glacier front between

2001 and 2005. Image: I. Howat et al. |

Greenland's glaciers have begun to race towards the ocean, leading

scientists to predict that the vast island's ice cap is approaching irreversible

meltdown, The Independent on Sunday can reveal.

Research to be published in a few days' time shows how glaciers that have been

stable for centuries have started to shrink dramatically as temperatures in

the Arctic have soared with global warming. On top of this, record amounts of

the ice cap's surface turned to water this summer.

The two developments - the most alarming manifestations of climate change to

date - suggest that the ice cap is melting far more rapidly than scientists

had thought, with immense consequences for civilisation and the planet. Its

complete disappearance would raise the levels of the world's seas by 20 feet,

spelling inundation for London and other coastal cities around the globe, along

with much of low-lying countries such as Bangladesh.

More immediately, the vast amount of fresh water discharged into the ocean

as the ice melts threatens to shut down the Gulf Stream, which protects Britain

and the rest of northern Europe from a freezing climate like that of Labrador.

The revelations, which follow the announcement that the melting of sea ice

in the Arctic also reached record levels this summer, come as the world's governments

are about to embark on new negotiations about how to combat global warming.

This week they will meet in Montreal for the first formal talks on whether

there should be a new international treaty on cutting the pollution that causes

climate change after the Kyoto protocol expires in seven years' time. Writing

in The Independent yesterday, Tony Blair called the meeting "crucial",

adding that it "must start to shape an inclusive global solution".

But little progress is expected, largely because of continued obstruction from

President George Bush.

The new evidence from Greenland, to be published in the journal Geophysical

Research Letters, shows a sudden decline in the giant Helheim glacier, a river

of ice that grinds down from the inland ice cap to the sea through a narrow

rift in the mountain range on the island's east coast.

Professor Slawek Tulaczyk, of the Department of Earth Sciences at the University

of California, Santa Cruz, told the IoS that the glacier had dropped 100 feet

this summer.

Over the past four years, the research adds, the front of the glacier - which

has remained in the same place since records began - has retreated four and a

half miles. As it has retreated and thinned, the effects have spread inland "very

fast indeed", says Professor Tulaczyk. As the centre of the Greenland ice

cap is only 150 miles away, the researchers fear that it, too, will soon be affected.

The research echoes disturbing studies on the opposite side of Greenland: the

giant Jakobshavn glacier - at four miles wide and 1,000 feet thick the biggest

on the landmass - is now moving towards the sea at a rate of 113 feet a year;

the normal annual speed of a glacier is just one foot.

The studies have found that water from melted ice on the surface is percolating

down through holes on the glacier until it forms a layer between it and the

rock below, slightly lifting it and moving it toward the sea as if on a conveyor

belt. This one glacier alone is reckoned now to be responsible for 3 per cent

of the annual rise of sea levels worldwide.

"We may be very close to the threshold where the Greenland ice cap will

melt irreversibly," says Tavi Murray, professor of glaciology at the University

of Wales. Professor Tulaczyk adds: "The observations that we are seeing

now point in that direction."

Until now, scientists believed the ice cap would take 1,000 years to melt entirely,

but Ian Howat, who is working with Professor Tulaczyk, says the new developments

could "easily" cut this time "in half".

There is also a more immediate danger as the melting ice threatens to disrupt

the Gulf Stream, responsible for Britain's mild climate. The current, which

brings us as much heat in winter as we get from the sun, is driven by very salty

water sinking off Greenland. This drives a deep current of cold ocean southwards,

in turn forcing the warm water north.

Research at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts has shown,

that even before the glaciers started accelerating, the water in the North Atlantic

was getting fresher in what it describes as "the largest and most dramatic

oceanic change ever measured in the era of modern instruments".

Even before these discoveries, scientists had shortened to evens the odds on

the Gulf Stream failing this century. When it failed before, 12,700 years ago,

Britain was covered in permafrost for 1,300 years.