Untitled Document

America's lawn-care industry is fighting hard to make sure the nation's

lawns are awash in synthetic fertilizers and pesticides.

|

An ad from Bayer Environmental

Science. As if toxic pesticides weren't scary enough... |

"I was boarding a flight in Atlanta and a couple of dozen troops with

the 101st Airborne, just back from Iraq, got on the plane. They were all fired

up about being home. I was sitting next to one of the guys. We chatted for a

while, and I asked him what three things he'd missed most over there.

"He listed -- in this order -- green grass, Domino's pizza, and beer.

In that order! I'm telling you, Stan, in this country, with our beautiful lawns

and parks, we take green for granted."

With that anecdote, Den Gardner, executive director of Project

Evergreen, underlined his organization's big message on lawn care: "You

can water, you can put on nutrients, you can use pesticides, and, yes, you can

apply organic products -- if they are used responsibly. And if your kid falls

down and rolls around on a soft, green lawn or soccer field, and doesn't get

hurt -- that didn't happen by chance!"

Gardner and I sat on a park bench in the midst of a vast carpet of green --

not grass, but a real carpet. Tools of the lawn-care trade -- mowers, sprayers,

blowers, sprinklers and spreaders, along with gallon jugs and 50-pound bags

of products to be sprayed, sprinkled and spread -- formed a backdrop stretching

out to what would have been the horizon, had we not been inside the Orlando

Convention Center.

The Green Industry Expo is an annual trade show for the lawn and landscaping

industry. It was held this month in conjunction with a Green Industry Conference

sponsored by the Professional Landcare Network, or PLANET. Project Evergreen

had a small booth and a high profile at the Expo. And its president, Paul McDonough,

spoke at the PLANET conference, declaring that his organization wants to be

"the green industry's 'Got Milk?' campaign."

An ad from Bayer Environmental Science. As if toxic pesticides weren't scary

enough...Gardner told me that from the moment Project Evergreen was formed in

2004, "activists tried to paint us as a front for the pesticide industry.

That really upsets me."

He explained that it's a much broader coalition: "When I started this

group, I called up about 25 people, from the turfgrass industry, golf course

superintendents, sports turf managers, equipment, pesticide, and fertilizer

manufacturers, PLANET, and others. I said, 'Let's get together and talk.'"

"Our goal," says Gardner, "is to set the record straight so

consumers can make their own decisions."

|

A self-guided mower, because human labor is just too unreliable. (Photo by Stan Cox) |

But Shawnee Hoover, special projects director at the environmental organization

Beyond Pesticides,

insists that Project Evergreen was formed in reaction to an increasing number

of local pesticide bans in Canada. Now, with pesticide and fertilizer regulations

being passed by some U.S. communities as well, Hoover says, "Project Evergreen

is using scare tactics to persuade landscapers that cutting their use of chemicals

will decimate the lawn care industry."

You need only look north, she says, to see that's not true: "In Canada,

where bans on toxic lawn chemicals have been implemented in over 70 municipalities,

the lawn care industry as a whole has continued to grow by 10 percent a year."

Green battlefield

A pesticide-and-fertilizer lobbying group called Responsible Industry for a

Sound Environment (RISE) made news earlier this year, announcing in its "2005

Outlook" report that "We are watching the entire United States, but

particularly the border states of New York, Connecticut, Maine, Wisconsin, Minnesota,

and Washington, for any activity relative to banning pesticides."

That image -- patrolling our border states to interdict and neutralize Canadian-style

environmentalism -- may seem a bit over-the-top, but it's right at home in the

"green industry," where vigilance and struggle are always prominent

themes.

Those themes were strikingly evident in Orlando. The industry's mascot may

be that linchpin of life on earth known as the chlorophyll molecule, but the

Green Industry Expo is all about horsepower, lethality, and hustle. (View scenes

of the 2005 GIE here.)

Let us spray

There's no question that chemistry plays a central role in the American lawn.

According to Project Evergreen's website, 50 percent of households treat their

lawns or gardens with pesticides, applying active ingredients at average annual

rates of 2 pounds per acre for herbicides and 0.4 pounds for insecticides. Professional

applicators apply an average 193 pounds of fertilizer per acre per year, while

do-it-yourself homeowners use 139 pounds.

Because nutrients, especially phosphorus, can run off fertilized yards and

sidewalks into storm drains or escape the shallow roots of turf grasses to pollute

groundwater, some states and communities have restricted fertilizer use.

Contrary to industry claims, a Minnesota study indicated that "lush

lawns are more of a water quality problem than poorer turf lawns,"

because of phosphorus runoff.

But it's pesticides that are the focus of most of the wrangling in Congress,

state legislatures and regulatory agencies these days.

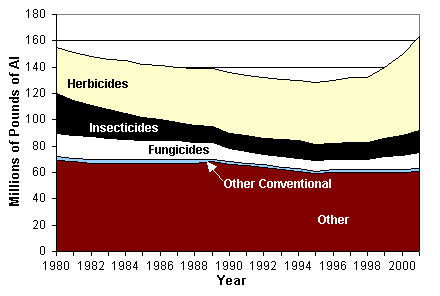

While agricultural use of pesticides has stagnated and industrial use has declined

in recent years, business is booming in the home-and-garden sector. According

to the Environmental Protection Agency's most recent statistics, home herbicide

use almost

doubled between 1982 and 2001.

Every two years, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

report on blood and urine concentrations of a wide variety of synthetic chemicals

in a representative sample of Americans. In the 1999-2000 sampling, 2,4-D (2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic

acid, one of the most widely used herbicides) was very rare or absent in the urine

of all age groups tested. But the report released in July of this year, covering

surveys from 2001-2002, 2,4-D was present in at least 25 percent of samples tested.

Anti-pesticide activists are forcefully targeting 2,4-D, citing a multitude

of studies from the scientific literature they say demonstrate its toxicity

to humans and other animals. Increased rates of lymphoma and bladder cancer

have even been found among dogs whose owners use 2,4-D.

And Beyond Pesticides cites published

research showing that 29 of the 30 most commonly used lawn pesticides are

toxic to birds, fish, amphibians, and/or bees.

|

A scene from the Green Industry Expo. This is the Hummer of fertilizers. (Photo by Stan Cox) |

In an appendix to its congressional testimony against a bill that would loosen

restrictions on pesticides under the Clean Water Act, Beyond Pesticides listed

summaries of a dozen studies from the mainstream scientific literature showing

adverse health effects of pyrethroids (a popular class of home-use insecticides

that the CDC also now finds common in human urine samples) on mice, rats, amphibians,

lobsters, and humans.

In contrast, I had seen on Project Evergreen's website a number of information

sheets citing the scientific literature and declaring pesticides generally safe

if used correctly. But Den Gardner told me, "We're a 501(c)3 nonprofit,

and not beholden to any interest groups. It's not our job to endorse any particular

piece of research. There are no scientists in our organization."

There is no law against nonprofit groups evaluating research. And lack of scientific

credentials has not stopped Project Evergreen from speaking out against local

natural-lawn initiatives.

When communities on Boston's North Shore joined in an effort to curb chemical

use, not by banning home pesticide use but simply through workshops on chemical-free

lawn care led by medical and organic experts, Gardner complained to a Boston

Globe reporter about misinformation

from some activists."

Project Evergreen often turns to the scientific community for backup. In the

group's tip sheet, "Banishing Pesky Pests to Create a Lush Lawn,"

associate professor Parwinder Grewal of Ohio State University explains the importance

of treating early and often with pesticides: "It is too late for grub control

when skunks have started digging the turf in search of a nice meal of fully

developed, juicy grub larvae."

Shawnee Hoover says, "Project Evergreen has shown that it is fiercely

against any kind of regulation of toxic chemicals. Isn't that a little strange

for a group supposedly only concernedwith the benefits of green landscapes?

"It's a deceptive front. It doesn't represent the interests of the public,

it represents the interests of the chemical industry, including RISE, Dow, Bayer,

and Syngenta."

All of those, she says, were on a membership list that has since been removed

from the organization's website.

Says Hoover, "Project Evergreen epitomizes the definition of 'greenwashing'."

From the farm to the lawn

In a 2003 paper published in the journal Antipode, Paul Robbins and Julie Sharp

of Ohio State University's Geography Department noted that, "Profits from

agricultural pesticides have been low for years," sending agrochemical

manufacturers in search of new markets. Today, "their most reliable customers"

are the makers of lawn-care products, who, in turn, are working to "increase

the ranks of chemical-using lawn managers."

Robbins and Sharp concluded, "Changes in the broader economy of agricultural

chemical manufacturing have paved the way for increases in the sales of lawn

chemicals."

Indeed, most of the products that were being promoted by Monsanto, Dow, Syngenta,

Bayer and other companies at the Green Industry Expo have the same active ingredients

as common agricultural pesticides. And, thanks to the National Institutes of

Health and EPA, there is now a huge body of epidemiological data on effects

of exposure to ag chemicals.

In an NIH/EPA Agricultural Health Study that has been running since 1993, scientists

have monitored the health of private and commercial pesticide applicators and

spouses. Almost 90,000 people have been included in the continuing study.

When I asked one of the project's leaders, Dr. Aaron Blair of the National

Cancer Institute, what has been learned so far, he summed up the situation this

way: "Evidence from experimental and epidemiological studies suggests that

some agricultural chemicals present risks to humans, but the magnitude of risk

and specific exposures have not yet been well characterized. Outcomes of concern

include cancer, neurologic diseases, reproductive problems, nonmalignant respiratory

diseases, and injuries."

Green that brings in the green

A burgeoning chemical-free-lawn movement is offering

loads of advice on alternative management of lawns, gardens and parks. But

experts emphasize that it's not simply a matter of substituting this organic

product for that synthetic one. Whole ecosystems have to be encouraged to regenerate,

and that doesn't happen overnight.

The whole-ecosystem approach also doesn't generate enough of that kind of green

that keeps the "green industry" going. As Robbins and Sharp put it

in their paper, "Any truly sustainable alternative is, put simply, bad

for business."

The Green Industry Expo is not the place to go to find stuff that's bad for

business; there was no reason to expect that any company would be there to urge

lawn-care providers to cut back on their purchased inputs and let nature take

over. But, I figured, somebody must at least be trying to cash in on environmental

concerns.

Weaving my way through rank after rank of mammoth, zero-turning-radius lawnmowers

-- the typical specimen resembling a hybrid between a lunar rover and a La-Z-Boy

recliner -- I searched for lawn-care approaches in a different shade of green..

LESCO of Cleveland, Ohio is one of the industry's major input suppliers. At

the sprawling LESCO display, marketing director Bob West told me that his company

does have an "Ecossentials" line of products, but he's seen "minimal

demand in isolated areas -- and you can probably guess where those areas are."

He grinned.

"Look at Cape Cod, where there's more sensitivity about environmental

issues. Our customers, the lawncare guys, might come in and ask for an organic

product because one of their customers, a homeowner, requested it. More often

than not, they'll end up going back to their traditional product. They find

out, one, that it costs more; two, that it takes longer to see results; and

three, they don't get the same level of results.

"It's a toughie. People say one thing with their emotions, another with

their wallet."

I sat through a PLANET workshop on "best practices," waiting in vain

for a discussion of thrift and restraint in chemical use. Speaker Bruce Wilson

of the Wilson-Oyler Group did mention worker-safety training, but the focus

was on vehicles and equipment.

Wilson had his own version of a three-item list: "Customers want to see

green grass, beautiful flowers, and no weeds. If those things are in place,

they're not looking at other stuff."

I resumed my search for alternatives, deep into shadows cast by the towering

John Deere, Dow and Monsanto displays. And here and there I hit pay dirt, so

to speak.

Gabe Diaz-Saavedra of Nature Safe Natural and Organic Fertilizers: "It's

a high-end niche market. Most typically not middle-class, but upper-class homes.

And you don't get that instant response a lot of people like. For instance,

it takes eight to 12 weeks to see disease suppression."

Tammy Kovar Dorton of Plant Health Care, whose products include fungal and

bacterial soil inoculants: "Green laws [that ban synthetic chemicals] are

helping, but it's a slow evolution."

Greg Gill of Nutrients Plus, which sells blends of poultry compost, biosolids

(i.e., sewage sludge), and standard synthetic fertilizers: "We're not tree-huggers.

We try to sell the best fertilizer, and environmental benefits like disease

and pest suppression are just icing on the cake. But most customers require

synthetic fertilizer in the mix, for aesthetic reasons. When they see that fertilizer

go down, they want to see green in a few days."

Who tells the story?

Last year, Project Evergreen put out an advertisement in the trade press, telling

the lawn and garden industry that "legislation and regulations have been

throwing the green industry some rough punches. And we're about to start fighting

back." The ad featured a pair of well-worn leather work gloves and a pugnacious

punchline: "The Gloves Are Off."

In line with what seems to be Project Evergreen strategy, there was no mention

of pesticides or synthetic fertilizers in the ad -- only a parenthetic comment

about "resources (such as water)." But it was widely viewed as an

effort by big corporations to fight local pesticide bans.

Beyond Pesticides countered with a parody of "The Gloves Are Off"

entitled "Get a Grip," in which a pair of flower-patterned garden

gloves lay on a lawn just as green (pdf

of both ads). It read, "The chemical lawn-care industry is worried that

the word is getting out on the toxic hazards of lawn pesticides."

Den Gardner admitted that the Project Evergreen ad was probably too aggressive.

"It was intended for landscape, lawncare, and other end-user businesses.

It was never intended as a consumer campaign. But activists took it and ran

with it. We learned there's no such thing as an internal issue in this business."

"But," said Gardner, looking on the bright side, "it also gave

us instant notoriety!"

He showed me the centerpiece of his group's new, and very different, campaign:

a photograph in which two young children sit on a manicured lawn, looking at

an empty Adirondack chair. On the arm of the chair lies a book titled "Because

Green Matters." The ad asks, "Who's telling your story?"

I asked Gardner how this campaign is being received in the "green industry."

He smiled. "It's resonating well."

Condition green

In their study of the lawn-chemical economy, Robbins and Sharp noted that "property

values are clearly associated with high-input green-lawn maintenance and use,"

and that "moreover, lawn-chemical users typically associated moral character

and social responsibility with the condition of the lawn."

Those are the economic and social buttons that the lawn-product makers and

Project Evergreen are pushing as they try to convince the "green industry,"

and you, that without constant vigilance, struggle, expense, and inevitably,

a bit of industrial chemistry, the world would fade to black, white and sepia

tones. Skunks would roam your front yard, feasting on fat, white grubs; you'd

see your kid limp home after playing soccer in a hard, dusty vacant lot; your

once-lush suburb would start to look like Sadr City.

That vision, however, is nowhere near as frightening as the toxic, ecologically

impoverished future envisioned by anti-pesticide activists. And the turf war

is on. Rounding a corner on the final day of the Expo, I came face to face with

a large photo of a helmeted soldier. Glaring through a slot in a concrete bunker,

he urged, "Defend your turf with Cavalcade. Make Cavalcade your weed control

weapon of choice this spring."

Except for the camouflage on his face and helmet, there was no green in the

picture.

Stan Cox is a plant breeder and writer in Salina,

Kansas. Since this past July, his

front lawn been lawn-free.