Untitled Document

|

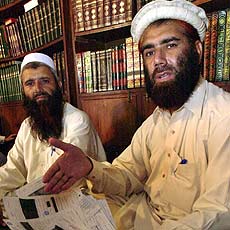

Brothers Badr Zaman Badr, right, and

Abdurrahim Muslim Dost show letters they received from family while in

prison, in which authorities blacked out portions. |

Badr Zaman Badr and his brother Abdurrahim Muslim Dost relish writing a good joke

that jabs a corrupt politician or distills the sufferings of fellow Afghans. Badr

admires the political satires in "The Canterbury Tales" and "Gulliver's

Travels," and Dost wrote some wicked lampoons in the 1990s, accusing Afghan

mullahs of growing rich while preaching and organizing jihad. So in 2002, when

the U.S. military shackled the writers and flew them to Guantanamo among prisoners

whom Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld declared "the worst of the worst"

violent terrorists, the brothers found life imitating farce.

For months, grim interrogators grilled them over a satirical article Dost had

written in 1998, when the Clinton administration offered a $5-million reward

for Osama bin Laden. Dost responded that Afghans put up 5 million Afghanis --

equivalent to $113 -- for the arrest of President Bill Clinton.

"It was a lampoon ... of the poor Afghan economy" under the Taliban,

Badr recalled. The article carefully instructed Afghans how to identify Clinton

if they stumbled upon him. "It said he was clean-shaven, had light-colored

eyes and he had been seen involved in a scandal with Monica Lewinsky,"

Badr said.

The interrogators, some flown down from Washington, didn't get the

joke, he said. "Again and again, they were asking questions about this

article. We had to explain that this was a satire." He paused. "It

was really pathetic."

It took the brothers three years to convince the Americans that they

posed no threat to Clinton or the United States, and to get released -- a struggle

that underscores the enormous odds weighing against innocent foreign Muslims

caught in America's military prisons.

In recent months, scores of Afghans interviewed by Newsday -- including a dozen

former U.S. prisoners, plus human rights officials and senior Afghan security

officials -- said the United States is detaining enough innocent Afghans in

its war against the Taliban and al-Qaida that it is seriously undermining popular

support for its presence in Afghanistan.

As Badr and Dost fought for their freedom, they had enormous advantages over

Guantanamo's 500-plus other captives.

The brothers are university-educated, and Badr, who holds a master's degree

in English literature, was one of few prisoners able to speak fluently to the

interrogators in their own language. And since both men are writers, much of

their lives and political ideas are on public record here in books and articles

they have published.

A Pentagon spokesman, Lt. Cmdr. Flex Plexico, declared this summer that "there

was no mistake" in the brothers' detention because it "was directly

related to their combat activities [or support] as determined by an appropriate

Department of Defense official." U.S. officials declined to discuss the

case, so no full picture is available of why it took so long for the pair to

be cleared.

The Pentagon's prison network overseas is assigned to help prevent attacks

on the United States like those of Sept. 11, 2001, so "you cannot equate

it to a justice system," said Army Col. Samuel Rob, who was serving this

summer as the chief lawyer for U.S. forces in Afghanistan. Still, he added,

innocent victims of the system are "a small percentage, I'd say."

The military is slow to clear innocent prisoners, largely because of its fear

of letting even one real terrorist get away, said Rob.

"What if this is a truly bad individual, the next World Trade Center bomber,

and you let him go? What do you say to the families?" asked Rob.

Rob and the Defense Department say the prison system performs satisfactorily

in freeing innocents and letting military investigators focus on prisoners who

really are part of terrorist networks. Badr and others -- including some former

military intelligence soldiers who served in Guantanamo and Afghanistan -- emphatically

disagree.

The United States for years called Badr and his brother "enemy combatants,"

but the men say they never saw a battlefield. And for an America that seeks

a democratized Afghanistan, they seem, potentially, allies. Americans "have

freedom to criticize your government, and this is very good," said Badr.

Also, "we know that America's laws say a person is innocent until he is

proven to be guilty," although "for us it is the reverse."

Badr and Dost are Pashtuns, members of the ethnic group that spawned the Taliban.

But the family library where they receive their guests is crammed with poetry,

histories and religious treatises -- mind-broadening stuff that the Taliban

were more inclined to burn than read. For years, the brothers' library has served

as a salon for Pashtun intellectuals and activists of many hues, including some

who also have been arrested in the U.S.-funded dragnet for suspected Islamic

militants.

Like millions of Afghans, they fled to Pakistan during the Soviet occupation

of their country in the 1980s and joined one of the many anti-Soviet factions

that got quiet support from Pakistan's military intelligence service. Their

small group was called Jamiat-i-Dawatul Quran wa Sunna, and Dost became editor

of its magazine. Even then, "we were not fighters," said Badr. "We

took part in the war only as writers."

After the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, the men split with Jamiat, partly over

its promotion of the extremist Wahhabi sect of Islam. Dost wrote lampoons against

the group's leader, a cleric named Sami Ullah, portraying him as a corrupt pawn

of its sponsor, Pakistan, working against Afghan interests.

In November 2001, as U.S. forces attacked Afghanistan, the mullah's brother,

Roh Ullah, "called us and said if we didn't stop criticizing the party

he would have us put in jail," said Badr. Ten days later, men from Pakistan's

Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate hauled the brothers off to grimy cells.

Another Ullah brother, Hayat Ullah, insisted in an interview that their family

had not instigated the arrests. Dost is a political rival, but "a very

simple man," Hayat Ullah said. "We have many powerful rivals. If I

were going to get ISI to pick up an enemy, why would I choose an ordinary person

like him?"

Pakistan-U.S. transfer

But two Pakistani analysts with sources in ISI said the Ullah family has been

accused in several cases of using its links to the agency to have rivals arrested.

And Roh Ullah himself is now imprisoned at Guantanamo.

In the midnight chill of Feb. 9, 2002, ISI officers led Badr and Dost, blindfolded

and handcuffed, onto the tarmac of Peshawar International Airport. When they

heard airplanes, "we knew they were handing us to the Americans,"

Badr said.

Beneath the blindfold, he stole glimpses of smiling Pakistani officers, grim

U.S. soldiers and a cargo plane. "It was a big festival atmosphere, as

though the Pakistanis were handing over Osama bin Laden to the United States,"

Badr said.

Shouting and shoving, American troops forced the brothers to the asphalt and

bound their hands behind them with plastic ties. "They chained our feet,"

Badr said. "Dogs were barking at us. They pulled a sack down over my head.

It was very difficult to breathe ... and I saw the flash of cameras. They were

taking pictures of us."

Flown to U.S. prisons at Bagram and Kandahar air bases in Afghanistan, the

brothers eventually learned from their interrogators that the ISI had denounced

them to the U.S. as dangerous supporters of the Taliban and al-Qaida who had

threatened President Clinton.

In the three-plus years that the brothers spent in U.S. prisons abroad, violent

abuse and torture were widely reported.

Eight of 12 men interviewed after their release in recent months from U.S.

prisons in Afghanistan told Newsday they had been beaten or had seen or heard

other prisoners being beaten.

The brothers escaped the worst abuse, partly because of Badr's fluent English.

At times, prisoners "who didn't speak English got kicked by the MPs because

they didn't understand what the soldiers wanted," he said. And both men

said that while many prisoners clammed up under questioning, they were talkative

and able to demonstrate cooperation.

"Fortunately, we were not tortured," Badr said, "but we heard

torture." At Bagram, "We heard guards shouting at people to make them

stand up all night without sleeping." At Kandahar, prisoners caught talking

in their cells "were punished by being forced to kneel on the ground with

their hands on their head and not moving for three or four hours in hot weather.

Some became unconscious," he said. The U.S. military last year investigated

abuse at its prisons in Afghanistan but the Pentagon ordered the report suppressed.

Routine interrogations

Badr and Dost were humiliated routinely. When being moved between prisons or

in groups, they often were thrown to the ground, like that night at Peshawar

airport. "They put our faces in the dust," Badr said.

Like virtually all ex-prisoners interviewed, he said he felt deliberately shamed

by soldiers when they photographed him naked or gave him regular rectal exams.

The brothers were flown to Guantanamo in May 2002 as soon as Camp Delta, the

permanent prison there, was opened. For more than two years, they sat in separate

cells, waiting days between interrogation sessions to explain and re-explain

their lives and writings.

In his 35 months in U.S. captivity, Badr said, he had about 150 interrogation

sessions with 25 different lead interrogators from several U.S. agencies. "And

that satire was the biggest cause of their suspicion," he said.

When one team of interrogators "began to accept that this was satire,"

the whole process would begin anew with interrogators from another agency. In

all, Badr said he was told that four U.S. agencies -- including the CIA, FBI

and Defense Department -- would have to give their assent before the men could

be released. And their names would be circulated to 40 other countries to ensure

they were not wanted anywhere else.

The Americans' investigations seemed to take forever to confirm even where

they had lived and studied. "I would tell him [the interrogator] something

simple and ... two or two-and-a-half months later, he would come back and say,

'We checked, and you were right about that,'" Badr said.

Another problem was that "Many of the interpreters were not good,"

said Badr. He recalled an elderly man, arrested by U.S. forces for shooting

his rifle at a helicopter, who explained that he had been trapping hawks and

fired in anger at one that flew away. But the interpreter mistook the Persian

word "booz" (hawk) for "baz" (goat). "The interrogator

became very angry," Badr said. "He thought the old man was making

a fool of him by claiming to be shooting at goats flying in the air."

Angered by ordeal

Rob conceded that "obviously, we could use more translators," but

said the pace at which prisoners are processed -- and innocents released --

is adequate.

That idea angers Badr. "They detained us for three and a half years,"

he said. "Then they said to us, 'all right, you're innocent, so go away.'"

Of that anger, Rob said, "that's understandable. Especially if he's the

breadwinner for his family and there's no one ... " The sentence hung uncompleted.

The brothers' anger is deepened by the abusiveness of many U.S. soldiers, whom

Badr compared to "Yahoos," the thuggish characters of Jonathan Swift's

"Gulliver's Travels." And they are upset that U.S. officials confiscated

all of their prison writings.

Still, Badr sounds neither bitter nor an enemy of America. "I am curious

to meet ordinary Americans," he said. "I appreciated my interrogators

in Guantanamo. ... Many of them were misguided, for example about my religion.

... But I can say that they were civilized people."