Untitled Document

|

Wal-Mart's team of marketing

specialists works in a second-floor conference room at the company's headquarters

in Bentonville, Ark. |

Inside a stuffy, windowless room here, veterans of the 2004 Bush and

Kerry presidential campaigns sit, stand and pace around six plastic folding

tables. Open containers of pistachio nuts and tropical trail mix compete for

space with laptops and BlackBerries. CNN flickers on a television in the corner.

The phone rings, and a 20-something woman answers. "Turn on Fox,"

she yells, running up to the TV with a notepad. "This could be important."

A scene from a campaign war room? Well, sort of. It is a war room inside

the headquarters of Wal-Mart,

the giant discount retailer that hopes to sell a new, improved image to reluctant

consumers.

Wal-Mart is taking a page from the modern political playbook. Under fire from

well-organized opponents who have hammered the retailer with criticisms of its

wages, health insurance and treatment of workers, Wal-Mart has quietly

recruited former presidential advisers, including Michael K. Deaver, who was

Ronald

Reagan's image-meister, and Leslie Dach, one of Bill

Clinton's media consultants, to set up a rapid-response public relations

team in Arkansas.

|

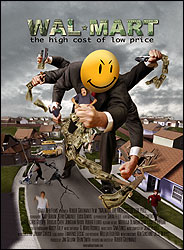

A documentary about Wal-Mart Stores is to open today in theaters. |

When small-business owners or union officials - also employing political

operatives from past campaigns - criticize the company, the war room swings

into action with press releases, phone calls to reporters and instant Web postings.

One target of the effort are "swing voters," or consumers who have

not soured on Wal-Mart. The new approach appears to reflect a fear that Wal-Mart's

critics are alienating the very consumers it needs to keep growing, especially

middle-income Americans motivated not just by price, but by image.

The first big challenge of the strategy will come Nov. 1 with the premiere

of an unflattering documentary. "Wal-Mart:

The High Cost of Low Price" was made on a shoestring budget of $1.8

million and will be released in about two dozen theaters. But its director,

Robert Greenwald, hopes to show the movie in thousands of homes and churches

in the next month. The possibility that it might become a cult hit like Michael

Moore's 1989 unsympathetic portrait of General

Motors, "Roger & Me," has Wal-Mart worried.

So, Wal-Mart has embarked on a counteroffensive that would have been unthinkable

even a year ago. Relying on a preview posted online, Wal-Mart investigated the

events described in the film and produced a short video contending the film

has factual errors. (Mr. Greenwald denies there are errors and says that Wal-Mart

has not seen the final cut.)

Wal-Mart has also begun to promote a second film, "Why Wal-Mart Works

& Why That Makes Some People Crazy," which casts the company in a rosier

light. Wal-Mart declined to make its executives available for the Greenwald

film, but it participated with the second film's director, Ron Galloway. The

war room team helped distribute a letter, written by Mr. Galloway, that challenges

Mr. Greenwald to show the two movies side-by-side.

To keep up with its critics, Wal-Mart "has to run a campaign," said

Robert McAdam, a former political strategist at the Tobacco Institute who now

oversees Wal-Mart's corporate communications. "It's simply nonsense for

us to let some of these attacks go without a response."

Wal-Mart's aggressive new posture is a departure from its tradition of relying

on an internal staff to manage the company's image. The war room, which is part

of a larger Wal-Mart effort to portray itself as more worker-friendly and environmentally

conscious, runs counter to the philosophy of the chain's founder, Sam Walton.

Believing that public relations was a waste of time and money, the penny-pinching

Mr. Walton would not likely have hired a public relations firm like Edelman,

Wal-Mart's choice to operate its war room.

So what has changed? For one thing, Wal-Mart's critics have become more sophisticated.

For years, unions hurled little more than insults at the chain. But over the

last year, two small groups - Wal-Mart Watch and Wake Up Wal-Mart - set up shop

in Washington with the goal of waging the public relations equivalent of guerilla

warfare against the company. Wal-Mart Watch received start-up cash from the

Service Employees International Union; Wake Up Wal-Mart is a project of the

United Food and Commercial Workers International Union. Unions have tried, unsuccessfully,

to organize Wal-Mart's employees.

At the suggestion of Wake Up Wal-Mart, members of the nation's largest teachers'

unions staged a boycott of Wal-Mart for back-to-school supplies this fall. Wal-Mart

Watch, meanwhile, set up an automated phone system that called 10,000 people

in Arkansas in June seeking potential whistle-blowers willing to share secrets

about the retailer.

Wal-Mart did not rebut such attacks, even when Wal-Mart Watch released a 24-page

report blasting the company's wages and benefits. Wal-Mart Watch said the report

had been downloaded from its Web site 55,000 times.

Once a darling of Wall Street, Wal-Mart's stock price has fallen 27 percent

since 2000, when H. Lee Scott Jr. became chief executive, a drop that executives

have said reflects, in part, investors' anxieties about the company's image.

Sales growth at stores open for more than a year has slowed to an average of

3.5 percent a month this year, compared with 6.3 percent at Target. And Wal-Mart

is facing growing resistance to new urban stores, with high- profile defeats

in Los Angeles, Chicago and New York.

There is some evidence that criticism is influencing consumers. A confidential

2004 report prepared by McKinsey & Company for Wal-Mart, and made public

by Wal-Mart Watch, found that 2 percent to 8 percent of Wal-Mart consumers surveyed

have ceased shopping at the chain because of "negative press they have

heard."

The Greenwald movie threatens to make matters worse. It features whistle-blowers

who describe Wal-Mart managers cheating workers out of overtime pay and encouraging

them to seek state-sponsored health care when they cannot afford the company's

insurance. And it travels across small-town America to assess the effects on

independent businesses and downtowns after a Wal-Mart opens.

The film is a particular concern now that Wal-Mart is trying to move upscale,

a strategy it hopes will appeal to higher-income consumers. In the last year,

Wal-Mart has introduced a line of urban fashions called Metro 7, hired hundreds

of fashion specialists to monitor how clothing is displayed in stores, and produced

more polished advertising.

But for the fashion strategy to pay off, Wal-Mart must win over a group of

shoppers who are sensitive to criticism of the chain's record - consumers, in

the words of Wal-Mart's chief executive, "who are not worried about their

next paycheck."

Hence the war room in Bentonville. Wal-Mart executives realized they were unprepared

to react to what Mr. Scott began to call the most expensive campaign ever waged

against a corporation. So the company quietly mailed a letter to the country's

biggest public relations firms several months ago seeking their help in developing

a response.

The contract went to Edelman, which assigned its top two Washington operatives

to the account. Wal-Mart would not say what it is paying Edelman, nor would

it allow interviews with the war room staff. Mr. Dach, who is active in environmental

and Democratic causes, was an outside adviser to President Clinton during the

impeachment battle. Mr. Deaver was President Reagan's communications director

and the creative force behind Mr. Reagan's so-called Teflon image.

Edelman also dispatched at least six former political operatives to Bentonville,

including Jonathan Adashek, director of national delegate strategy for John

Kerry, and David White, who helped manage the 1998 re-election of Representative

Nancy Johnson, a Connecticut Republican. Terry Nelson, who was the national

political director of the 2004 Bush campaign, advises the group.

In turn, Wakeup Wal-Mart is led by, among others, Paul Blank, former

political director for the Howard

Dean presidential campaign, and Chris Kofinis, who helped create

the DraftWesleyClark.com

campaign.

Wal-Mart Watch's media team includes Jim Jordan, former director of

the Kerry campaign, and Tracy Sefl, a former Democratic National Committee aide

responsible for distributing negative press reports about President Bush during

the 2004 campaign.

The war room staff arrives at Wal-Mart's headquarters, a short drive from a

nearby corporate apartment where they live, by 7 every morning. The group works

out of an old conference room on the second floor, christened Action Alley,

the same name Wal-Mart gives to the wide, circular aisle that runs around its

stores.

Three display boards are covered with to-do lists. One says: "Promote

Week of 10/24/05: MLK Memorial Donation. Urban/blighted community plan."

Two large maps show the location of Wal-Mart and Sam's Club stores across the

United States.

The team starts the day by scanning newspaper articles and television transcripts

that mention Wal-Mart. Next come conference calls with Wal-Mart employees around

the country to plan for events. Whenever possible, Mr. McAdam said, the war

room will try to neutralize criticism before it is leveled.

That was the strategy behind what Action Alley considers its first coup. In

late September, after several unions broke off from the A.F.L.-C.I.O., the splinter

groups announced they would hold a convention in St. Louis on a Tuesday.

Action Alley members, assuming Wal-Mart would be a target of criticism during

the union gathering, arranged for Wal-Mart to hold its own news conference the

day before. It invited three local suppliers, a sympathetic local official and

a cashier to say that Wal-Mart had a positive effect on the community.

"If you look at many of the stories that were written about that overall

convention, they've got our messages in them," Mr. McAdam said. "In

the past, when we've just responded to something somebody else is doing, it's

sort of 'you know, by the way, Wal-Mart says ...' We got ahead of this one."

A campaign atmosphere pervades Action Alley. A small bus with the words "Clinton-Gore"

on the side sits on the table. When discussing Wakeup Wal-Mart, Wal-Mart Watch

and the Greenwald movie, Mr. McAdam slips into political-speak.

"The people who show up at Mr. Greenwald's film are probably not swing

voters," he said. "They are probably the true believers of their point

of view and I doubt there is a heck of a lot we can do to change their minds."

Mr. McAdam continued: "They've got their base. We've got ours. But there

is a group in the middle that really we all need to be talking to."