Untitled Document

|

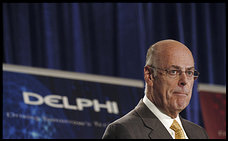

The man and the message: After

seeking Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, Delphi's Robert "Steve" Miller

warned his workers of drastic cuts, saying "It may not be fair, but it

is reality." |

The scene in Lower Manhattan was reminiscent of teenagers rushing to the front

of a concert stage, only this time it was middle-aged lawyers and Wall Street

bankers who pushed elbow to elbow into a federal courtroom no bigger than a gas

station mini-mart.

The throng of pinstripe suits forced court aides to call in workers to pry

open windows for ventilation, allowing U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Robert D. Drain

to proceed with the Oct. 11 opening-day hearing regarding the "petition

for relief" by Michigan auto parts maker Delphi Corp. under Chapter 11

of federal bankruptcy laws.

Once shunned by respectable companies and ignored by Wall Street, federal

bankruptcy court has become the venue of choice for sophisticated financiers

and corporate managers seeking to pull apart labor contracts and roll back health

and welfare programs at troubled companies.

About 150 major corporations are now in some stage of bankruptcy reorganization,

including four of the nation's leading airlines. As the prospect of other large

enterprises taking a spin down Chapter 11 becomes more widely discussed in business

circles ("maybes" on the list include such iconic names as General

Motors and Ford), the tactics used in bankruptcy courts are shaking the very

foundations of the American workplace.

Whether an assembly-line worker or middle manager, an employee can

no longer assume that promises made earlier -- health benefits or fully funded

pensions -- will be there when he or she retires. The loss of security arising

from Chapter 11 reorganizations has introduced a new element of anxiety into

the lives of baby boomers who are approaching 60, not to mention younger workers

just starting out in their careers.

The new bankruptcy law, which took effect last week, will have little

effect on corporate bankruptcies. The legislation, approved by Congress

and signed by President Bush in April, is aimed at curbing abuses in consumer

bankruptcies. It tightens the rules for individual filings, making it more difficult

for consumers to have their credit card and other debts wiped clean in court.

But except for barring certain bonus payouts, the new law keeps intact the

legal system by which corporations can shed certain employee obligations, including

pension costs that can be shifted to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. (PBGC),

which Congress set up in 1974 to insure defined-benefit corporate pensions.

The PBGC is now struggling with $23.3 billion in net deficits arising from

the termination of pension plans from Chapter 11 bankruptcies in the steel and

airline industries. Delphi's filing shifts the spotlight onto the pension problems

of the auto sector, where a total shortfall ranges between $45 billion and $50

billion, according to the PBGC's estimates.

Why the surge in corporate bankruptcies at a time when the economy is expanding?

The explanation heard most often is two-fold: global competition and out-of-control

labor costs. Competition from low-wage assembly plants in Mexico and Asia is

tightening the screws on American manufacturers who must pay top-dollar wages

to unionized workers as well as promised pension and health benefits, known

as "legacy costs," to retirees.

"Legacy costs are killing us," says Robert S. "Steve" Miller,

who was named Delphi's chairman and CEO last July. Miller is emblematic of the

shifting nature of bankruptcy law. A self-styled "corporate doctor,"

he has a law degree from Harvard University, a master's degree in finance from

Stanford University and a blunt speaking style that makes him quotable in the

media.

Before taking Delphi into Chapter 11 on Oct. 8, Miller made it known that unionized

employees represented by the United Auto Workers (UAW) would have to accept

either a wage reduction of 62 percent, from an average of $26 an hour to as

little as $10 an hour, or sharp benefit reductions to retirees. UAW President

Ron Gettelfinger denounced the offer as insulting, but Miller defended it at

a news conference. The CEO couldn't have been more explicit in describing his

view of the modern workplace: "Some people insist that fairness requires

that we slash wages across the board if we cut wages for anyone. Well, I am

sorry. My job is to preserve the value of this enterprise as we restructure.

We have to adjust to market conditions and appropriately pay for our human capital

at each level. There are large disparities in this country and around the world

in what people can expect for mowing the lawn, versus managing a huge business.

It may not be fair, but it is reality."

The Delphi chief often cites reality -- and the bottom line -- in answering

his critics. "They [have to] understand that I haven't got any more money,"

Miller told the Financial Times.

But the reality, to use Miller's word, isn't so simple. Delphi does have money

-- specifically, it has $1.6 billion in cash on hand. Even more significantly,

it secured $2 billion in loans and revolving credit from Citigroup and J.P.

Morgan Chase bank just before it filed for bankruptcy. Which raises a question

that the common explanation for Chapter 11 filings doesn't answer: If Delphi

is so broke, with unsustainable wage costs and skyrocketing pension obligations,

why are two of the nation's major banks offering to lend it money on excellent

credit terms?

The answer: For the same reason that Bank of America, General Electric Capital

Group, UBS Securities and distressed property, or "vulture," capitalists

have invested billions of dollars in supposedly tattered companies entering

or exiting Chapter 11 since 2001. Investors can profit richly from the meltdown

of established companies -- at least in the short run. Chapter 11 protects a

company from creditors as management develops a reorganization plan and restructures

its liabilities in the hope of becoming profitable again. Older companies may

have high legacy costs, but they have long-term customer contracts and plenty

of cash flow.

"The way the code is now structured, the temptation is to make the workforce

pay for management's mistakes, rather than taking all of the stakeholders into

account and re-building the company together," says Harley Shaiken, a professor

at the University of California at Berkeley who specializes in labor issues.

Chapter 11 calls on management to bargain with unions in good faith to reduce

costs, but also permits management to petition the court to void labor contracts

and substitute whatever terms it chooses. Properly stage-managed and set in

motion, the restructuring process can steamroll the union, peel away retiree

benefits and dump pension obligations onto the PBGC.

That's exactly what happened during Miller's 19-month tenure as chief executive

of Bethlehem Steel. Some 95,000 retirees and dependents lost their health-care

plan in 2003 when the bankruptcy judge sold the company's assets to International

Steel Group, a company controlled by billionaire financier Wilbur L. Ross.

Meanwhile, the PBGC was left with the responsibility of paying $4.3 billion

in underfunded Bethlehem pensions over the next 30 or so years. Because of the

less generous terms of PBGC's pension formula, some steelworkers lost 50 percent

of their expected pensions as well as their health benefits.

Earlier this year, Ross sold International Steel to London-based Mittal Steel

Co., picking up $267 million in profit on the sale. Ross's investment fund has

since amassed $4.5 billion, some of which he plans to use to make acquisitions

in the auto parts industry, he said recently. One of his possible targets? Delphi.

He has made it clear, in recent interviews, that he is carefully watching the

company and its Chapter 11 reorganization.

So what others see as an ailing business, Ross sees as an opportunity.

Economists often talk about "moral hazard" and "free rider"

systems that create incentives for governments or common citizens to behave

imprudently and follow short-term strategies that can cause long-range problems.

Bankruptcy law can encourage such behavior.

Established by Congress in 1898 as a part of the U.S. district court system,

early bankruptcy courts were auction houses where court-appointed referees settled

claims among squabbling creditors. Little interest was shown in keeping a company

on legal life support until the Great Depression when, faced by an unprecedented

number of business failures, the Chandler Act of 1938 created Chapter 11 bankruptcies

to allow managers to try restructuring instead of simply liquidating the assets.

The present system dates to the 1978 Bankruptcy Act, which made it easier for

a business to file for protection and gave management broad rights to set forth

a reorganization plan under the supervision of a bankruptcy judge. The act changed

the economic ground rules. Before 1978, few law firms bothered having a bankruptcy

department; afterward, nearly every "white-shoe" firm opened up thriving

bankruptcy and restructuring practices.

Bankers were not far behind. Rather than fighting with management over existing

assets, they began to underwrite management's reorganization plans through "debtor

in possession" loans and revolving credit. This gave them priority claim

on company assets if reorganization didn't work (something not offered to employees,

who are in the heap of unsecured creditors), and offered lavish rewards to managers

who cut costs.

This helps explains an aspect of the Delphi filing that has puzzled observers:

CEO Miller's petition to the court to award up to $87 million in bonuses to

senior managers, who also would share 10 percent of the equity in the reorganized

company.

Logic would suggest that a dynamic corporate doctor would want to amputate,

not remunerate, the people who helped get the company in trouble in the first

place. Bonuses and equity, however, "incentivize" managers, to use

Wall Street lingo, to remain at the company and meet the downsizing targets

set by Miller.

It's one of those disembodied tactics of modern business life in which there

is no apparent crime -- only victims, such as retirees who lose their benefits,

and Middle American towns that lose a part of their tax base when the local

Delphi plant is padlocked.

Aside from the question of social equity, is Chapter 11 an effective cure for

a sick company? There is little evidence that court-supervised reorganization

produces a superior company. In fact, quite a few companies that come out of

bankruptcy make a return trip, and there is growing evidence that the process

diverts capital away from needed investments into the pockets of the restructurers.

"Moral hazard" warns us against letting poorly run companies undercut

the practices of strong companies. It would be a pity, says Shaiken, to encourage

responsible companies to follow in the Chapter 11 footsteps of weak ones, rending

the social and economic fabric of years of comparative labor peace.

You don't have to be UAW's Ron Gettelfinger to be bothered by the contrast

between the winners and losers of recent Chapter 11 reorganizations. The enrichment

of managers and financiers who parachute into troubled industries is unacceptable

if taken from the benefits promised to workers who served their employers loyally

in return for a measure of security in their golden years.