The Rev. Dr. Martin

Luther King Jr. set forth the goal. Civil rights and union membership

were to be intertwined. The labor movement, Dr. King wrote in 1958, "must

concentrate its powerful forces on bringing economic emancipation to white and

Negro by organizing them together in social equality."

That happened in the 1960's and 1970's. But then unions lost bargaining

power and members. And while labor leaders called attention to the overall decline,

few took notice that blacks were losing much more ground than whites.

In the last five years, that trend accelerated. Despite a growing economy,

the number of African-Americans in unions has fallen by 14.4 percent since 2000,

while white membership is down 5.4 percent.

For a while in the 1980's, one out of every four black workers was

a union member; now it is closer to one in seven. This loss of better-paying

jobs helps to explain why blacks are doing worse than any other group in the

current recovery. Labor leaders have acknowledged the disproportionate damage

to African-Americans, but they decline to make special efforts to organize blacks

and offset the decrease, saying that all groups need help. That lack of priority

angers one prominent black scholar.

"The future of black workers is very bleak indeed if they lose their place

in the union movement," said William Julius Wilson, a professor of sociology

and social policy at Harvard. "I would hope there would be an effort on

the part of union leaders, white and black, to address this very important issue.

They haven't done so as yet."

|

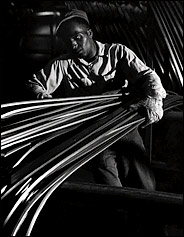

A worker at a Chrysler plant

in Detroit in 1952. Unionization helped many blacks get good-paying jobs

in the 1960's and 70's. |

The decline was particularly sharp last year. Overall union membership fell

by 304,000, and blacks accounted for 55 percent of that drop, the Bureau of

Labor Statistics reports, even though whites outnumber blacks six to one in

unions (12.4 million to 2.1 million). The trend seems likely to continue and

perhaps accelerate as General Motors and its principal parts supplier, Delphi,

cut costs in their struggle to be profitable.

"We have lost 20,000 members since the end of 2000 in Detroit and its

suburbs alone," said Linda Ewing, director of research for the United Auto

Workers, "and a large number of the workers in the auto and parts plants

in this area are black."

Unions, like other institutions in the post-World War II economy, were slow

to admit African-Americans to the club, and there is still resistance today

in some of the higher-paying skilled trades. Yet blacks came to rely on unions

even more than working class whites did to gain entry into the middle class,

through jobs that gave them annual wage increases and company-paid health insurance

and pensions. Even now, the percentage of black workers who are in unions is

slightly greater than the percentage of unionized white workers: 15.1 versus

12.2. "Every survey shows that blacks are the group that most wants to

be unionized," said Richard Freeman, a Harvard labor economist.

Graphic

Dwindling

Membership

Immigration, retirement, automation, the shifting of work overseas, low seniority

and privatization have all played a role in the lopsided decline of unionized

jobs held by African-Americans. That decline is especially noticeable in manufacturing

and the federal government, two strongholds of black employment that have gone

through cutbacks in union workers in recent years.

The cutbacks are particularly severe in the auto industry. In addition to the

latest problems at G.M., Ford Motor said Thursday that it would soon announce

"significant plant closings."

The impact on blacks has gradually drawn the attention of labor leaders, including

John J. Sweeney, president of the A.F.L.-C.I.O. "The percentage of black

workers who have been knocked out of union jobs is one of the little-known tragedies

of the last five years," he said.

Despite this damage, the federation is not making a special effort to sign

up more African-Americans in other industries, Mr. Sweeney said. "We are

going to be organizing more blacks," he explained, "but we are also

going to be organizing more Latinos and more women."

Mr. Sweeney's reluctance to single out blacks has its counterpart in the breakaway

union movement, Change to Win, which promises more aggressive organizing. Rather

than focus on any particular group of workers, said Edgar Romney, secretary-treasurer

of the new coalition, "we are targeting industries and communities in our

organizing effort."

Blue-collar workers earn high pay in manufacturing jobs, and the sharp decline

in black union membership in that sector has helped to pull down the median

weekly wage of all black workers, union and nonunion alike. Thus far this year,

the median weekly wage earned by blacks fell by 5 percent, to $523, adjusted

for inflation, according to an analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Whites as a group are also experiencing a drop in their median weekly wage,

but for them the decline this year is less than 1 percent, to $677, adjusted

for inflation.

Some labor economists bridle at such comparisons. Robert Topel of the University

of Chicago argues that for many years the wage gap between whites and blacks

either shrank or remained stable, after adjusting for differences in education,

experience and other factors. This occurred even as union power declined, he

said.

"If you ask me for a list of things that would be more important in understanding

racial disparities and economic success, unionism would not be high on the list,"

Mr. Topel said. "Education, development of skills and family environment

all play much bigger roles than collective bargaining power."

The decline in black union membership is not simply the result of the erosion

of employment in manufacturing. The Service Employees International Union, for

example, represented for years large numbers of African-Americans employed in

food service, janitorial work and nursing home care. Many were women. As they

retired, Hispanics and Asians replaced them, in the jobs and as union members,

said Patricia Ford, a former executive vice president of the S.E.I.U.

"You can see the change from what was traditionally African-American to

Hispanic," Ms. Ford said. "That is the most striking."

Union membership among Hispanics, in fact, has risen gradually in this decade,

to 1.7 million last year. That is partly a result of special efforts to organize

Hispanics in service industries, Mr. Romney said.

On another front, privatization and outsourcing have eaten away at federal

employment of black workers represented by the American Federation of Government

Employees, which says that nearly 25 percent of its 211,000 members are black.

African-Americans make up an even higher percentage of the union's members

at the operations that the Bush administration is turning over to private contractors.

These include laundries at veterans' hospitals, ground maintenance and food

service at government installations and security guards at numerous federal

buildings - much of it work that paid only $15,000 to $20,000 a year, but that

came with pensions and health insurance.

The union's leaders resist viewing what is happening in racial terms. "We

see it as a class issue rather than a race issue," said Sharon Pinnock,

the A.F.G.E.'s director for membership and organization. "It is impacting

all workers, black and white."

Automation at the Postal Service, mainly in the form of sorting machines that

require many fewer workers, has cut into the ranks of the National Association

of Letter Carriers and the American Postal Workers Union, both with high percentages

of blacks among their members.

And then there is the tendency of many corporations to move operations to suburbs

from downtown locations. In the process, unionized African-American workers

are often replaced by nonunion workers, in many cases white.

The Communications Workers of America makes that complaint, citing customer

service call center operations as one example. "They gradually move to

the suburbs, eliminating African-American union members in the city," said

George Kohl, the union's senior director of collective bargaining.

Mr. Sweeney said such stories anger him. "We have learned a lot from the

civil rights movement; it is important that we highlight the most egregious

offenses," he said. "But we have to focus on all the workers who are

getting hurt."