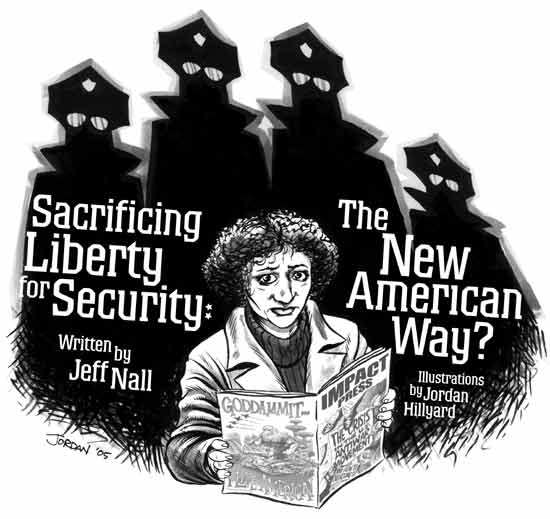

Untitled Document

I recently learned that I have my own FBI file. You might be surprised

to find out that your activities are being monitored, as well, whether you feel

they deserve to be or not. And, with Congress restoring nearly all of the PATRIOT

Act's sun-setting provisions to their scorching, oppressive noon day glory,

the time has come to ask ourselves—has freedom finally fallen to the fatalistic

tandem of fear and security?

People like U.S. Attorney Michael J. Sullivan, District of Massachusetts, don't

think so. Earlier this year, Sullivan argued that the "reauthorization

of the USA PATRIOT Act will maintain the proper balance between guarding our

civil liberties and protecting our homeland from those who seek to harm us"

("PATRIOT Act has not hurt civil liberties," The Standard-Times, May

25, 2005). And Attorney General Alberto Gonzales echoed the Bush administration,

proclaiming that the PATRIOT Act is necessary to "protect our country against

another terrorist attack." ("Gonzales defends USA PATRIOT Act,"

The Advocate, August 8, 2005).

Others dismiss the ACLU's claim that the FBI has made a habit of targeting

groups and individuals because of their liberal brand of politics ("Documents

Obtained by ACLU Expose FBI and Police Targeting of Political Groups,"

ACLU press release, May 18, 2005). Meanwhile, Bush supporters frequently complain

that liberals are simply blowing things out of proportion and that the occasional

intrusive measure is necessary in order to win the war on terrorism. I, however,

fear the worst; that the brilliant blues of American pride are fading into the

dull bruises of a nation that has lost its constitutional soul.

As an activist, I experienced, firsthand, the gross abuses such optimistic

and faithful voices are deaf to. Last January 20, I joined about three dozen

peaceful demonstrators in taking to the streets of Melbourne, Florida, to mourn

the "reelection" of President Bush. In a funeral-style procession,

we walked down one of the city's central thoroughfares brandishing anti-Bush

posters, a nine-foot banner that read, "not a mandate," and hand-crafted

Styrofoam headstones, commemorating the liberties eroding under the Bush administration.

The plan was to march from a nearby park to city hall. There we would break

the headstones and refuse to bury our rights. But by the time we had arrived

at city hall, about 45 minutes into the event, it was clear our rights had already

been buried. Our group of about 36 protestors, including four children, a woman

in a wheelchair, and at least four people over the age of 60, was met by nine

city police officers. Worst of all, one police officer, a member of the crime

scene investigation unit, was stationed across the street where he filmed the

entire protest.

|

After the event, the Brevard County chapter of the ACLU obtained records about

the police presence at the event. It turned out that former Melbourne police

chief Keith Chandler had enacted a policy that made videotaping of anti-administration

demonstrations a routine procedure. Chandler did so following the issuance of

an FBI memo, in October 2003, which instructed law enforcement in the ways of

monitoring legal protests. With the aid of an apologetic City of Melbourne police

chief, Don Carey, whose organization unintentionally recorded a suspicious SUV

that turned out to be from the Brevard County Sheriff's Office (BCSO) and who

implemented new rules to protect the exercise of free speech and discarded the

routine videotaping policy, the ACLU discovered that the BCSO had coordinated

intense, covert surveillance of the event.

The initial information released showed that officers, under the direction

of Bruce Parker, Director of the Investigative Support Unit for the BCSO, photographed

the license plates of demonstrators' parked cars, while others took photos of

participants from the aforementioned unmarked SUV. At least one undercover officer

infiltrated the demonstration. The sheriff's office even notified security at

nearby Patrick Air Force Base about the event.

The BCSO had generated a list of six "persons of interest," a label

often used when referring to suspected criminals. The records also showed that

the BCSO had obtained the date of birth, Social Security number and address

of each of the six listed persons. In my case, the BCSO directly referred to

me as a "suspect," took down my car's VIN number, and had my email

address.

In a follow-up records request, the BCSO released more than 500 pages revealing

expansive surveillance operations around the entire county. The BCSO had not

only spied on our demonstration, but had also conducted similar investigations

of more than 10 other protests. Beginning back in 2002, the officers took photos

and did background checks on members of the Cape Canaveral Coalition for Racial

Justice. They also monitored events organized by the Global Network Against

Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space, the International Association of Longshoremen,

and Patriots for Peace (PFP), which organized several pre-war peace demonstrations.

In the case of PFP, a group I helped organize, the BCSO assigned an undercover

officer to attend and report on peace rally planning meetings. To top it all

off, the records revealed that my activism had somehow earned me an FBI number.

(Even an issue of IMPACT Press, which I had previously written for, was scanned

and placed into the file.)

Not surprisingly, all the groups the BCSO scrutinized were left-leaning organizations.

In contrast, records show that BCSO attended only one right-leaning rally, "Rally

for America," a support the troops/pro-Iraq war event. Though the event,

held in March 2003, was attended by more than 1,000 people, BCSO took no photos

and made no lists as it had done at other events. In fact, BCSO was actually

present at the behest of the event's organizers who were concerned about potential

counter-protestors.

When Bruce Parker attempted to publicly rebuff the accusation that the BCSO

targeted liberal organizations, he only succeeded in solidifying his bias: "A

pro-America rally does not attract anarchists to participate in the rally, except

for those who might come to counter-protest. If they don't show up there, there's

nothing to record [license] tags for. We're looking for anarchists that are

going to commit violent acts" ("ACLU seeks reforms in county spy policy,"

Florida Today, May 16, 2005). Parker's comments beg the question, if anarchists

wouldn't participate in a "pro-America" rally, why is he so convinced

they'd participate in racial equality protests, peace demonstrations, and civil

rights rallies? After all, what's more American than making use of the First

Amendment and peaceably assembling? The answer lies with Sgt. Andrew Walters,

the sheriff's spokesman. When asked what the six counter-inauguration participants,

labeled "persons of interest," were of interest for, Walters said

"Protesting in an anti-government assembly" ("Spying on citizens",

Florida Today, March 23, 2005). Evidently, in the eyes of the sheriff's office,

the only kinds of "pro-government" assemblies are cheerleading rallies

praising the policies of the Bush administration.

|

In response to a torrent of media attention and fiercely critical newspaper

editorials, Bruce Parker defended the surveillance tactics: "Before this

last protest, demonstrators didn't even know we were present. We were there

to make sure there were no protestors who could potentially be a problem, like

a group of anarchists—to know who was there we had to get license tag

numbers" ("Records reveal more spying," Hometown News, May 13,

2005). Parker said September 11 made such tactics necessary and even alluded

to the fact his organization was working with the FBI: "We don't want there

to be another September 11 where police agencies didn't do as much as they could

do to follow up on leads that were available . . . If we find anything, we immediately

take it to the FBI" ("ACLU seeks reforms in county spy policy,"

Florida Today, May 16, 2005).

Considering the instructions of the once classified 2003 FBI memo, it's pretty

clear that the FBI is leading local law enforcement agencies, like the BCSO,

down a blurry path where constitutional dissent begins to look like terrorism:

"Law enforcement agencies should be alert to possible indicators of protest

activity and report any potentially illegal acts to the nearest FBI Joint Terrorism

Task Force." The memo also advises: "Extremist elements may engage

in more aggressive tactics that can include . . . trespassing, the formation

of human chains or shields, makeshift barricades . . . peaceful techniques can

create a climate of disorder."

In other words, agencies like the BCSO, likely acting on the FBI's directive

to preemptively monitor the activities of lawful activists, are treating dissenters

as they would terrorists. Epitomizing this purposeful convolution of the war

on terror and a crackdown on dissent, Sheriff Jack Parker said this, in defending

his organization's monitoring of the counter-inauguration rally: "We must

both uphold the freedoms provided by the Constitution and at the same time protect

the lives of our citizens. This is a delicate balance . . . Terrorists use anti-government

activities to form alliances and recruit persons to perform acts of terrorism.

If we did not take a special interest in activities that could attract terrorists,

we would not be doing our job."

By equating First Amendment protected demonstrations to "anti-government

activities" that attract terrorists, law enforcement leaders like Sheriff

Parker prove to be inept defenders of the First Amendment. Blinded by ever-increasing

policing powers, men like Bruce Parker can hardly tell the difference between

ordinary Americans marching to preserve freedom and democracy in the U.S., and

those associated with the Oklahoma City bombing. Responding to criticism over

the surveillance of counter-inauguration protesters, Bruce Parker retorted,

"We were trying to protect the citizens of the county. We want to make

sure there is not another Terry Nichols among the protesters" ("Police

had interest in war protestors," Hometown News, March 25, 2005).

By last June, Sheriff Parker had seemingly changed his tune, announcing that

his agency would henceforth only gather intelligence on demonstrators who pose

"an identifiable potential for violence." But the ambiguity of this

language—what constitutes such "an identifiable potential"?—has

satisfied few concerns, and raised new questions. Besides, with the PATRIOT

Act fully renewed and back at his side, Guantanamo's the limit.

Though the ominous surveillance of lawful citizens in Brevard County has not

yet been linked to the PATRIOT Act directly, Kevin Aplin, vice president of

the Brevard ACLU, says one thing is certain: "We do know that the [Bush]

administration has set a political climate where law enforcement feels emboldened

to collect surveillance on First Amendment protected activities, using the war

on terrorism as justification. The sheriff here has said they're looking for

terrorists. So they're certainly using the war on terror to justify collecting

intelligence on citizens that have broken no laws and are engaging in lawful

First Amendment activities."

While many in the community decried such egregious policing, many fully agreed

that secret monitoring and otherwise unconventional tactics were necessary in

the interest of safety. During a city council meeting on the subject, Melbourne

Mayor Harry Goode commented that extreme security measures were sometimes necessary

because terrorists want to destroy everything that is America. "This is

a whole different United States than the one we grew up in," he said ("Police

to stop videotaping protesters," Florida Today, February 23, 2005). Many

Brevard County residents writing into the local paper agreed. Bill Logan wrote:

"Knowing we are under tight security since 9/11, and also knowing there

are terrorist cells within our borders, they don't stop to think why police

were filming. It's for their own protection." Anthony Marchione wrote,

"There are many legitimate reasons to use various surveillance methods,

some of which are not necessarily open to public scrutiny" (Letters to

the Editor, Florida Today, March 13, 2005).

With fear guiding so many toward faith in security, the U.S. may travel a path

not unlike that prophesied by an 80-year-old dystopian novel, We. Written by

Russian author Yevgeny Zamyatin, We tells the story of a society, the One State,

that decides the "only means of ridding man of crime is ridding him of

freedom." To achieve its utopian society of perfect peace, the One State

eradicates individuality, privacy, and freedom; and the citizens exalt the Guardians

(secret police), who monitor their every action, for "lovingly protecting"

them.

As America flees the open skies of liberty for the patriarchal shelter of authoritarianism,

perhaps it's only a matter of time before we turn to the transparent walls of

the One State: "At all other times we live behind our transparent walls

that seem wove of gleaming air—we are always visible, always washed in

light. We have nothing to conceal from one another. Besides, this makes much

easier the difficult and noble task of the Guardians. For who knows what might

happen otherwise?"