Untitled Document

How much influence do private networks of the rich and powerful have

on government policies and international relations? One group, the Bilderberg,

has often attracted speculation that it forms a shadowy global government. As

part of the BBC's Who Runs Your World? series, Bill Hayton tries to find out

more.

|

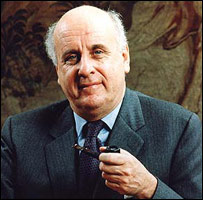

Bilderberg's head Viscount

Davignon plays down the group's role in setting the international agenda |

The chairman of the secretive - he prefers the word private - Bilderberg Group

is 73-year-old Viscount Etienne Davignon, corporate director and former European

Commissioner.

In his office, on a private floor above the Brussels office of the Suez conglomerate

lined with political cartoons of himself, he told me what he thought of allegations

that Bilderberg is a global conspiracy secretly ruling the world.

"It is unavoidable and it doesn't matter," he says. "There will

always be people who believe in conspiracies but things happen in a much more

incoherent fashion."

Lack of publicity

In an extremely rare interview, he played down the importance of Bilderberg

in setting the international agenda. "What can come out of our meetings

is that it is wrong not to try to deal with a problem. But a real consensus,

an action plan containing points 1, 2 and 3? The answer is no. People are much

too sensible to believe they can do that."

Every year since 1954, a small network of rich and powerful people

have held a discussion meeting about the state of the trans-Atlantic alliance

and the problems facing Europe and the US.

Organised by a steering committee of two people from each of about

18 countries, the Bilderberg Group (named after the Dutch hotel in which it

held its first meeting) brings together about 120 leading business people and

politicians.

At this year's meeting in Germany, the audience included the heads

of the World Bank and European Central Bank, Chairmen or Chief Executives from

Nokia, BP, Unilever, DaimlerChrysler and Pepsi - among other multi-national

corporations, editors from five major newspapers, members of parliament, ministers,

European commissioners, the crown prince of Belgium and the queen of the Netherlands.

"I don't think (we are) a global ruling class because I don't think a

global ruling class exists. I simply think it's people who have influence interested

to speak to other people who have influence," Viscount Davignon says.

|

Bill Clinton was featured at a Bilderberg meeting while he was governor of Arkansas |

"Bilderberg does not try to reach conclusions - it does not try to say 'what

we should do'. Everyone goes away with their own feeling and that allows the debate

to be completely open, quite frank - and to see what the differences are.

"Business influences society and politics influences society - that's

purely common sense. It's not that business contests the right of democratically-elected

leaders to lead".

For Bilderberg's critics the fact that there is almost no publicity

about the annual meetings is proof that they are up to no good. Jim Tucker,

editor of a right-wing newspaper, the American Free Press for example, alleges

they organise wars and elect and depose political leaders. He describes the

group as simply 'evil'. So where does the truth lie?

Professor Kees van der Pijl of Sussex University in Britain says such private

networks of corporate and political leaders play an informal but crucial role

in the modern world.

"There need to be places where these people can think about the main challenges

ahead, co-ordinate where policies should be going, and find out where there

could be a consensus."

'Common sense'

Will Hutton, an economic analyst and former newspaper editor who attended a

Bilderberg meeting in 1997, says people take part in these networks in order

to influence the way the world works, to create what he calls "the international

common sense" about policy.

"On every issue that might influence your business you will hear at first-hand

the people who are actually making those decisions and you will play a part in

helping them to make those decisions and formulating the common sense," he

says.

And that "common sense" is one which supports the interests of Bilderberg's

main participants - in particular free trade. Viscount Davignon says that at

the annual meetings, "automatically around the table you have internationalists"

- people who support the work of the World Trade Organisation, trans-Atlantic

co-operation and European integration.

Bilderberg meetings often feature future political leaders shortly

before they become household names. Bill Clinton went in 1991 while still governor

of Arkansas, Tony Blair was there two years later while still an opposition

MP. All the recent presidents of the European Commission attended Bilderberg

meetings before they were appointed.

'Secret Government'

This has led to accusations that the group pushes its favoured politicians

into high office. But Viscount Davignon says his steering committee are simply

excellent talent spotters. The steering committee "does its best assessment

of who are the bright new boys or girls in the beginning phase of their career

who would like to get known."

"It's not a total accident, but it's not a forecast and if they go places

it's not because of Bilderberg, it's because of themselves," Viscount Davignon

says.

But its critics say Bilderberg's selection process gives an extra boost

to aspiring politicians whose views are friendly to big business. None of this,

however, is easy to prove - or disprove.

Observers like Will Hutton argue that such private networks have both good

and bad sides. They are unaccountable to voters but, at the same time, they

do keep the international system functioning. And there are limits to their

power - a point which Bilderberg chairman was keen to stress, "When people

say this is a secret government of the world I say that if we were a secret

government of the world we should be bloody ashamed of ourselves."

Informal and private networks like Bilderberg have helped to oil the wheels

of global politics and globalisation for the past half a century. In the eyes

of critics they have undermined democracy, but their supporters believe they

are crucial to modern democracy's success. And so long as business and politics

remain mutually dependent, they will continue to thrive.