Untitled Document

DOUGLAS, Ariz., Aug. 18 - Spent shells litter the ground at what is left of the

firing range, and camouflage outfits still hang in a storeroom. Just a few months

ago, this ranch was known as Camp Thunderbird, the headquarters of a paramilitary

group that promised to use force to keep illegal immigrants from sneaking across

the border with Mexico.

|

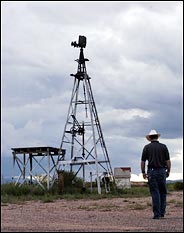

A windmill tower in Douglas,

Ariz., was a lookout point for members of a group that tried to prevent

illegal immigrants from crossing the border. |

Now, in a turnabout, the 70-acre property about two miles from the border is

being given to two immigrants whom the group caught trying to enter the United

States illegally.

The land transfer is being made to satisfy judgments in a lawsuit in which

the immigrants had said that Casey Nethercott, the owner of the ranch and a

former leader of the vigilante group Ranch Rescue, had harmed them.

"Certainly it's poetic justice that these undocumented workers own this

land," said Morris S. Dees Jr., co-founder and chief trial counsel of the

Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Ala., which represented the immigrants

in their lawsuit.

Mr. Dees said the loss of the ranch would "send a pretty important message

to those who come to the border to use violence."

The surrender of the ranch comes as the governors of Arizona and New Mexico

have declared a state of emergency because of the influx of illegal immigrants

and related crime along the border.

Bill Dore, a Douglas resident briefly affiliated with Ranch Rescue who is still

active in the border-patrolling Minuteman Project, called the land transfer

"ridiculous."

"The illegals are coming over here," Mr. Dore said. "They are

getting the American property. Hell, I'd come over, too. Get some American property,

make some money from the gringos."

|

Camp Thunderbird is two miles from the Mexican border. |

The immigrants getting the ranch, Edwin Alfredo Mancía Gonzáles

and Fátima del Socorro Leiva Medina, could not be reached for comment.

Kelley Bruner, a lawyer at the law center, said they did not want to speak to

the news media but were happy with the outcome.

Ms. Bruner said that Mr. Mancía and Ms. Leiva, who are from El Salvador

but are not related, would not live at the ranch and would probably sell it.

Mr. Nethercott bought the ranch in 2003 for $120,000.

Mr. Mancía, who lives in Los Angeles, and Ms. Leiva, who lives in the

Dallas area, have applied for visas that are available to immigrants who are

the victims of certain crimes and who cooperate with the authorities, Ms. Bruner

said. She said that until a decision was made on their applications, they could

stay and work in the United States on a year-to-year basis.

Mr. Mancía and Ms. Leiva were caught on a ranch in Hebbronville, Tex.,

in March 2003 by Mr. Nethercott and other members of Ranch Rescue. The two immigrants

later accused Mr. Nethercott of threatening them and of hitting Mr. Mancía

with a pistol, charges that Mr. Nethercott denied. The immigrants also said

the group gave them cookies, water and a blanket and let them go after an hour

or so.

The Salvadorans testified against Mr. Nethercott when he was tried by Texas

prosecutors. The jury deadlocked on a charge of pistol-whipping but convicted

Mr. Nethercott, who had previously served time in California for assault, of

gun possession, which is illegal for a felon. He is now serving a five-year

sentence in a Texas prison.

Mr. Mancía and Ms. Leiva also filed a lawsuit against Mr. Nethercott;

Jack Foote, the founder of Ranch Rescue; and the owner of the Hebbronville ranch,

Joe Sutton. The immigrants said the ordeal, in which they feared that they would

be killed by the men they thought were soldiers, had left them with post-traumatic

stress.

Mr. Sutton settled for $100,000. Mr. Nethercott and Mr. Foote did not defend

themselves, so the judge issued default judgments of $850,000 against Mr. Nethercott

and $500,000 against Mr. Foote.

Mr. Dees said Mr. Foote appeared to have no substantial assets, but Mr. Nethercott

had the ranch. Shortly after the judgment, Mr. Nethercott gave the land to his

sister, Robin Albitz, of Prescott, Ariz. The Southern Poverty Law Center sued

the siblings, saying the transfer was fraudulent and was meant to avoid the

judgment.

Ms. Albitz, a nursing assistant, signed over the land to the two immigrants

last week.

"It scared the hell out of her," Margaret Pauline Nethercott, the

mother of Mr. Nethercott and Ms. Albitz, said of the lawsuit. "She didn't

know she had done anything illegal. We didn't know they had a judgment against

my son."

This was not the first time the law center had taken property from a group

on behalf of a client. In 1987, the headquarters of a Ku Klux Klan group in

Alabama was given to the mother of a boy whose murder was tied to Klansmen.

Property has also been taken from the Aryan Nations and the White Aryan Resistance,

Mr. Dees said.

Joseph Jacobson, a lawyer in Austin who represented Mr. Nethercott in the criminal

case, said the award was "a vast sum of money for a very small indignity."

Mr. Jacobson said the two immigrants were trespassing on Mr. Sutton's ranch

and would have been deported had the criminal charges not been filed against

Mr. Nethercott.

He criticized the law center for trying to get $60,000 in bail money transferred

to the immigrants. While the center said the money was Mr. Nethercott's, Mr.

Jacobson said it was actually Ms. Nethercott's, who mortgaged her home to post

bail for her son.

Mr. Nethercott and Mr. Foote had a falling out in 2004, and Mr. Foote left

Camp Thunderbird, taking Ranch Rescue with him. Mr. Nethercott then formed the

Arizona Guard, also based on his ranch.

In April, Mr. Nethercott told an Arizona television station, "We're going

to come out here and close the border with machine guns." But by the end

of the month, he had started his prison sentence.

Now, only remnants of Camp Thunderbird remain on his ranch, a vast expanse

of hard red soil, mesquite and tumbleweed with a house and two bunkhouses. One

bunkhouse has a storeroom containing some camouflage suits, sleeping bags, tarps,

emergency rations, empty ammunition crates, gun parts and a chemical warfare

protection suit.

In one part of the ranch, dirt is piled up to form the backdrop of a firing

range. An old water tank, riddled with bullet holes, is on its side. A platform

was built as an observation post on the tower that once held the water tank.

Charles Jones, who was hired as a ranch hand about a month before Mr. Nethercott

went to prison, put up fences and brought in cattle to graze. He has continued

to live on the property with some family members.

But now the cattle are gone, and Mr. Jones has been told that he should prepare

to leave. "It makes me sick I did all this work," he said.

Ms. Nethercott said she was not sure whether her son knew that his ranch was

being turned over to the immigrants, but that he would be crushed if he did.

"That's his whole life," she said of the ranch. "He'd be heartbroken

if he lost it in any way, but this is the worst way."