Untitled Document

President George W. Bush has embedded murder, assassination, torture, and mistreatment

of prisoners into the structure of the U.S. system of global domination. Many

U.S. citizens, rightly outraged, want to know why this sort of barbaric, sadistic

violence has become an integral part of U.S. security policy, and what the Administration’s

justification of torture means institutionally for the future governance of this

country. Above all, they want to know how Bush has been able to avoid impeachment

for committing high crimes.

Here is a select list of typical tortures, abuses, and “outrages against

human dignity” inflicted by U.S. forces and mercenaries on enemy captives

in the course of their arrest, detention and interrogation:

Beating, kicking, and treading on bodies

Sleep deprivation and forced injection of drugs

Rape and sodomy

Water torture, a traditional U.S. Army practice since at least the Indian wars

and the Philippines insurrection at the end of the 19th century

Hanging prisoners whose arms are bound behind their back by shackles or handcuffs

until their limbs pop from their sockets—a new U.S. form of lynching

Tight handcuffing, close-shackling, and blindfolding or “hooding”

for extended periods; sometimes the hoods are marked in order to alert the U.S.

torturer to the particular crime that the prisoner is suspected of having committed

Forced stripping of Muslim prisoners and keeping them naked for long periods

Religious humiliation

Sexual humiliation, insult, and debasement, including smearing with feces, urine,

and what appears to be menstrual blood

Screaming racial insults before, during, and after unleashing violence against

captives

Shocking with electrical instruments, another method of torture commonly used

by U.S. troops in Vietnam

Exposure for prolonged periods to extremes of light and dark, heat and cold,

and noise so deafening as to rupture the eardrums

Extraction of nails, burning skin with cigarettes, stabbing or cutting the bodies

of prisoners

Threatening prisoners or their relatives with death or by having them watch

other victims being tortured

Threatening with dogs or allowing dogs to actually assault prisoners during

or before interrogation

Forcing prisoners to stand or to remain in painful positions for extended periods

Isolation in cells, cages, wooden boxes, and barbed wire-enclosed trailers for

prolonged periods

Depriving prisoners of food, water, drink, and toilet facilities

Extreme or enforced rendition, i.e., torture by proxy in foreign countries

These acts were performed both before and after the Bush administration had

unilaterally exempted itself from legal liabilities under international and

domestic law. Some members of the U.S. military abused prisoners because senior

military commanders such as Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez had explicitly authorized

them to do so; some tortured the enemy because they found it to be “fun”;

but most seem to have acted in the belief that their conduct was condoned because

the White House and the Department of Defense had adopted a policy of fighting

terror with terror.

In the U.S. mass media the routine, sometimes bone-shattering beating of prisoners

in U.S. custody receives relatively little attention except as a public relations

problem. Moral and legal concern seems to be reserved for the less common, more

secretive practice of “rendition,” in which officials of the executive

branch are protected because the abuse takes place outside the U.S., avoiding

monitoring by the Red Cross and due process. More so than other modes of torture,

this type of contract crime may be ordered mainly for reasons of deterrence—i.e.,

to teach an object lesson to all people who fall afoul of the U.S., regardless

of their national origin. European governments rightly consider it to be a blatant

violation of their local sovereignty and are investigating.

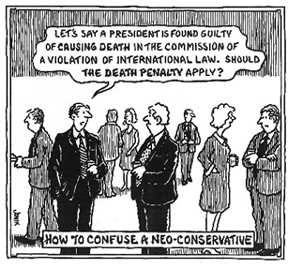

A Total War Strategy

The Bush administration’s increasing reliance on imprisonment, torture,

and assassination as elements in its “war on terror,” needs to be

explained from multiple angles, as part of a total war strategy for eliminating

new challenges to the U.S. global empire. Fear, racism, and colonial wars in

poverty-stricken Afghanistan and Iraq are historical frames that highlight the

scope and complexity of the problem. The collapse of separation of powers, the

decay of democratic processes and values, Congress’s unwillingness to

destroy the perception of presidential impunity, and the increasingly secret

nature of government combine to constitute a fourth frame. Let me touch briefly

on each.

From the earliest days of the U.S., fear and racism have been striking features

of U.S. culture. Although closely related, they are distinguishable. By fear

I mean the inordinate susceptibility of the U.S. public to fits of real panic,

during which fear and extremism override reason. Usually fear spreads when political

elites sound the alarm and rally the country to fight some unbelievably powerful

force that is out to destroy the world they inhabit. The threat can come from

within or from outside, from a modern or a “failed state,” or from

a social movement. But once defined, U.S. citizens imagine that only extraordinary

leaders, willing to ignore the law, can protect them from the menace. Under

strong presidents, citizens fight back in self-defense against the insidious

enemy, using catastrophic weapons created by their technological genius. The

enemy can be Indians, Blacks, or Chinese; it can be Britain in one period, Spain,

Japan, the Soviet Union, or international terrorists in another. In almost every

case, the enemy that their leaders exhorted them to hate later turns out to

be whoever had something we wanted. The pattern is old and recurs throughout

the history of U.S. empire. The most spectacular case of “punishing an

aggressor” with an unprecedented new super weapon was President Truman’s

nuclear destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

By racism I mean attitudes of hatred and contempt directed toward those who

are unlike us, mainly for reasons of color. In multicultural, allegedly color-blind

U.S., with its many racial minorities, racism and de facto segregation continues.

When Bush declared his “war on terror,” this old dynamic assumed

forms suited to 21st century conditions. Racial profiling returned; civil rights

for minorities and immigrants eroded; and both developments went hand in hand

with war atrocities committed by U.S. forces in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Guantanamo,

Cuba.

The effects of racial bias can be seen in the world’s largest, expanding

prison system, where the percentage of Blacks, Latinos, and Hispanics remains

high and racial violence and mistreatment of minority inmates occurs frequently.

Not surprisingly, in the atmosphere of revenge galvanized by the 9/11 attacks,

racial violence quickly spread from the domestic prisons and police departments

to U.S. military prisons abroad. Abusive jailers and police officers from the

U.S. volunteered to fight and ended up torturing prisoners at camps in Kandahar,

Baghram, Guantanamo Bay, Mosul, Bucca in southern Iraq, and Abu Ghraib near

Baghdad.

The Pentagon also recruited patrol officers and officials from the federal

and state prisons for its war on terror and sent them to the U.S.-run prisons

in Iraq. According to Bureau of Justice Statistics, the U.S. state prison system

is far larger than the federal system and in 2003 held nearly 1.2 million inmates,

most of them ethnic minorities. Local jails contained 700,000 inmates; juvenile

facilities over 100,000. Racial violence and mistreatment of inmates by guards

is more likely to occur in the state prisons and local jails where the level

of discipline is lower, the use of force greater. But from the Brooklyn Metropolitan

Detention Center, where hundreds of Muslim detainees were recently abused, to

the U.S. military prisons spread throughout the world, wherever prisoners of

color have been tortured by guards, racism usually lies close to the surface.

Furthermore, race rather than national origin fundamentally shapes the U.S.

soldiers’ image of the terrorist. The Army sent to fight in Afghanistan

and Iraq was “whiter” than it had been since 2000 as a result of

five straight years of declining Army recruitment of black Americans. The 17,000

U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan reportedly turned virtually the entire country

into one huge secret prison in which military guards and CIA interrogators inflicted

gratuitous pain on the bodies of individual Afghani captives who are held incommunicado

without charge or trial, according to a March 19, 2005 report in the Guardian.

Whenever this happens the likelihood is great that they are exercising “racially-informed,”

irrational violence against both their victims and the entire society to which

they belong. The same phenomenon can be seen in Iraq where U.S. soldiers call

the inhabitants “sand niggers” and “ragheads.”

A third framework for understanding the torture scandal is the regressive,

colonial-like character of the current U.S. wars. Nothing illustrates this better

than the bloody struggle to control Fallujah, a Sunni city located west of Baghdad

on the edge of the Iraq desert, which before the U.S. invasion had a population

estimated at 300,000.

The initial skirmish in what became the first battle of Fallujah (March and

early April 2004) was fought after four U.S. military contractors were brutally

murdered by young Iraqis. The killings were in revenge for the murder in Gaza

of the paraplegic Sheik Ahmed Yassin, spiritual leader of Hamas, by Israelis

who were flying U.S. helicopters. Marines went into Fallujah allegedly searching

for the killers of the civilian mercenaries but were forced out by its residents.

To redeem their honor they mounted a full-scale assault. After three weeks of

rebellion the casualty figures ranged from a low of 600 combatant and non-combatants

killed and over 1,200 injured to estimates ranging upward from 1,000.

The second battle to retake Fallujah from its inhabitants began five months

later in November 2004, after Marines again cut off food, water, and electricity

to the city in violation of the Geneva Conventions. Their illegal acts of collective

retribution were designed to empty the city of its women, children, and elderly

while preventing the departure of able-bodied Iraqi civilian males. When something

similar happened in Srebrenica, Bosnia in 1995 it was universally condemned

in Europe and the U.S. as “genocide.” The main difference was that

in Srebrenica the Serbs evacuated the women and children by truck while in Fallujah

the U.S. bombed them out.

As U.S. ground attacks on entrances to the besieged city of Fallujah increased,

aerial bombardment—torture from the air—commenced. A U.S. specialty

since 1945, the bombing of cities tends to take a primary toll on civilians

while seeking to force both noncombatants and combatants to sue for peace.

Iraqi popular resistance forces responded to these U.S. assaults by stepping

up attacks in Baghdad, Samarra, Ramadi, and elsewhere, killing and wounding

more foreign occupiers and their Iraqi collaborators by the week. Fallujah’s

struggle to end U.S. occupation spread the nationalist resistance.

The retaking of Fallujah during November and early December through ruthless

air, tank, and artillery bombardment resulted in the city’s complete destruction.

Under rules of engagement approved in Washington, U.S. forces reportedly used

banned napalm and poison gas, killed civilians holding white flags or white

clothes over their heads, murdered the wounded, killed unarmed Iraqis who had

been taken prisoner, and destroyed mosques, hospitals, and health centers protected

under international law. One of the most amazing, well reported scenes from

this battle took place at the Fallujah General Hospital where U.S. forces kicked

down doors, cut the telephone lines, molested doctors, forced patients from

their beds, and manacled their hands behind their backs. The hospital, said

U.S. military spokesperson, was releasing casualty figures useful for the propaganda

of the resistance fighters.

Fallujan residents were dispossessed of their homes and forced to live as refugees

in surrounding towns and villages. To this day no one knows how many people

died in the bloodbath. But a few months earlier, in September 2004, an Iraqi

mortality researcher and his interviewer, working on a public health study jointly

sponsored by Johns Hopkins University and Columbia University, managed to enter

the city. What they discovered was such a high number of civilian deaths that

they decided to exclude the Fallujah data from their final, conservative estimate

of about 100,000 Iraqi civilians (mostly women and children) killed since the

U.S. invaded. In a population estimated at 24 million, that is the U.S. proportional

equivalent of 1.2 million deaths.

When legal restraints are removed during a war, needless death and destruction

occurs; invariably the main victims are highly vulnerable civilians. In World

War II, the “kill ratio” was one civilian death (mostly children,

women, and the elderly) for every soldier killed. The smaller wars fought after

1945 ran the civilian-soldier count up to 8:1. But in Iraq the kill ratio is

conservatively estimated to be much higher. Why do tens of millions of Americans

refuse to confront this reality? Perhaps because they never heard about the

Lancet study, thanks to the U.S. corporate media. Or perhaps misguided patriotism

and militarism, drummed into youth through film, television, and video games,

lead them to consider the enormous civilian loss and suffering as unavoidable

“collateral damage” or a product of military necessity. Whatever

the reasons, not only the Administration, but the mainstream press and many

citizens profess to care only about the lives of fellow Americans and remain

unconcerned about the barbaric treatment their soldiers mete out to Iraqis and

Afghanis.

U.S. Assertion of Dominion

The problem of widespread, individualized interrogation-by-torture is inseparable

from the pain and suffering inflicted on all those who resist U.S. assertion

of dominion. In late April 2004, as the initial battle for Fallujah was winding

down, the first photos appeared of uniformed, grinning U.S. soldiers torturing

Iraqis at Abu Ghraib prison. Since then, the illegal acts of the Bush administration,

its armed forces, and intelligence operatives have received relentless news

media attention abroad and only desultory attention within the United States.

Earlier, there had been news reports coming out of Afghanistan about teams

of U.S. Special Forces and their Northern Alliance allies committing war atrocities

at Baghram, Kandahar, and other places in Afghanistan. UN officials had documented

how uniformed U.S. officers connived in the mass killing of surrendered Taliban

soldiers at Dash-E Leili. NGOs in many countries, including the International

Red Cross, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International, had compiled massive

dossiers documenting, from early 2002 onward, U.S. soldiers severely beating

and kicking bound, helpless prisoners, and of Army medical personnel conniving

in the abuse. Often recessed into the background of such reports was mention

of U.S. forces treating Afghanis mercilessly, as subhuman, denigrating them

through the use of racial epithets, demeaning their national culture.

Many people in the U.S. took news of atrocity charges in stride. During 2003,

stories broke of Israeli military advisers being invited into Iraq and to Fort

Bragg, North Carolina to train U.S. assassination squads. Neither did video

pictures of U.S. helicopter pilots murdering wounded Iraqis lying on the ground

or the U.S. seizure without charge of foreign nationals and their shipment to

prisons outside the jurisdiction of U.S. courts for purposes of torture. Well

before the obscene photos from Abu Ghraib and their broadcast on national television

struck a spark, the foreign place-names for atrocities committed by U.S. forces

were steadily increasing. But the U.S. chose either not to know or to passively

accept the president’s disregard of international law. When Bush boasted

in his State of the Union speech in 2003, “The course of this nation does

not depend on the decisions of others,” apologists for his unilateralism

chimed in that “lawful” and “unlawful” had ceased to

be meaningful terms.

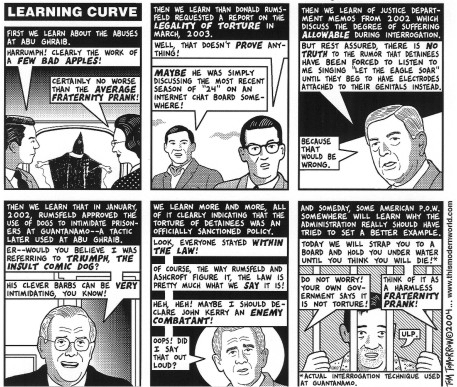

By the time the torture scandal broke, Iraqi resistance against the U.S. presence

had intensified and public support for the war was waning. The Bush administration

rushed to deny that torture was intentionally ordered or widely practiced and

blamed all abuses on a few rotten apples, acting on their own. Neither Bush

nor Rumsfeld offered a public apology for torture nor admitted that they had

prior knowledge of it. Congress and the public accepted the official White House/Pentagon

version of events.

Yet the daily routine of U.S. war crimes was too widespread to be covered up.

The story of the prisons staffed with racists and sadists, just as in the U.S,

kept deepening; the number of prisoners kept on increasing—in Iraq, 8,000

at the time of the Abu Ghraib pictures, 10,500 as of March 2005; and in Afghanistan

500 as of January 2005.

Bush policy-makers had expressed from the outset a strong desire to inflict

pain on enemy captives. They had denied the occupied peoples proper prisoner-of-war

treatment, set aside the law of occupation, and ordered military strategies

of indiscriminate violence against all who resisted their aims. Documents generated

in the White House and the Departments of Justice and Defense appeared in the

press after lawsuits were brought by the ACLU. They bore out that the president,

by fiat, had set aside the Geneva Conventions, denied prisoner-of-war status

to Taliban and Al Qaeda captives taken in Afghanistan, and sent them for indefinite

detention to the naval base at Guantanamo, Cuba. This meant they would be interrogated

without legal restriction under Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s

rules, which violated the Constitution, not to mention Bush’s worthless

public promise to treat them humanely.

The torture documents reveal a mindset within the White House and Pentagon

intent on destroying what remains of democratic processes. Right after the World

Trade Center and Pentagon attacks, Bush issued a secret directive authorizing

the torture by proxy in foreign jails of those suspected of having information

about terrorist operations. Thereafter he used the “war on terror”

and his commander-in-chief authority to expand the little known “state-secrets

privilege,” for which no constitutional foundation exists, in order to

prevent the courts from discovering what crimes he has directed the CIA to commit.

The torture debate is about the Pentagon’s and the White House’s

cover-up of the massive war crimes committed by members of the U.S. armed forces

and CIA against Afghanis and Iraqis. But at a deeper level it is part of a larger

debate in which the issues at stake are:

Bush’s usurpation of power and his attempt to elevate the myth of presidential

sovereignty

Bush’s illegal attempt to exempt the U.S. from the Geneva Conventions

and his Administration’s invention of the false category of “unlawful

combatants” as a way of legitimating indefinite confinement and torture

The evocation of “presidential secrecy” by executive officials to

prevent the federal courts from prying into matters of national security both

as they concern the Pentagon’s and the CIA’s global prison systems

and Bush’s dereliction in the performance of his duties

The federal Constitution’s modeling of the presidency on monarchy and

its failure to protect from periodic presidential usurpations of power, which

is exactly what its chief author, James Madison, intended

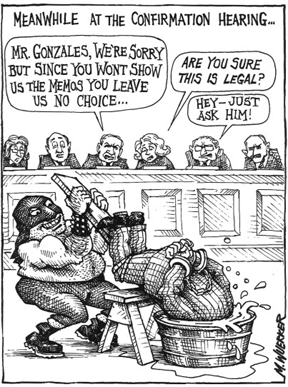

Turning to government memoranda, we see the most senior-level bureaucrats, lawyers,

politicians, and soldiers—all of whom had sworn oaths to uphold the Constitution—debating,

over a two-year period, (a) how to justify Bush’s decision to use interrogation

techniques that were explicitly banned by international and domestic law; (b)

how to limit the president’s legal exposure in the event that a federal

district court tried to block him from getting around the law by issuing a writ

of habeas corpus; and (c) how to prevent a court from assessing whether U.S.

conduct in Afghanistan violated the norms of international law.

Another little known finding is that the U.S. may never have ratified any human

rights convention without adding reservations that exempted itself—not

the 1949 Geneva Conventions, not the subsequent protocols to it, and not even

the 1948 Genocide Convention, which is the first of the post-World War II human

rights treaties. Technically the Senate ratified the 1984 Torture Convention

in 1994, but only after changing the definition of torture to make it more restrictive

“than that set out in the Convention,” and thus more “interrogator-friendly.”

The torture documents show President Bush and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld

using the legal opinions of their lawyers—including the now notorious

August 1, 2002 memo written by Assistant Attorney General Jay S. Bybee—to

assert a right to order the torture, maiming, and even murder of prisoners.

Drawing on his commander-in-chief authority and the advice of his counsel, Alberto

Gonzales, Bush suspended the Geneva Conventions, but later, in order to protect

himself, issued a written directive cautioning all military interrogators to

treat detainees “humanely.” At the same time, he allowed CIA interrogators

to continue using cruel and unusual methods of interrogation. Bush also authorized

the use of torture techniques against prisoners detained in the war on Iraq,

which initially had nothing to do with the war against the Taliban or Al Qaeda.

Rumsfeld took charge and turned the Pentagon into the “nerve center for

directing torture and conducting secret missions.”

Over the years since U.S. forces entered Afghanistan and later attacked and

occupied Iraq, U.S. soldiers have scoured villages, towns, and cities in both

countries, searching for “insurgents.” Overall, they succeeded mainly

in creating chaos and lawlessness, spreading armed resistance to their presence,

and generating a keen desire for future revenge against the United States. The

more U.S. forces have devastated Iraq, contaminated its land, destroyed its

cities, and mistreated the Iraqi people in their local communities and inside

their homes, the more resistance to U.S. presence has grown.

Tens of thousands of Iraqi civilians, as well as al-Qaeda suspects and Taliban

fighters, have been rounded up and imprisoned under medieval conditions. U.S.

soldiers, CIA agents (“case officers”), and mercenaries (“civilians”)

working for privatized military firms under contract to the Pentagon, are known

to have sadistically tortured large numbers of them while having their deeds

photographed and filmed so that they could be seen by friends back home.

The Logic of Torture

A fourth frame for understanding why torture became just another weapon in the

U.S. arsenal relates to the long decline in the spirit of democratic government

that preceded 9/11. The growing immunity of the military from Congressional oversight

is but an aspect of this phenomenon. At its heart is the corruption of the Congress

under one-party control and the connivance of Senators and House members in shielding

the president and his advisers from criminal liability for waging wars of aggression

in which they themselves were complicit. The U.S. was already out of step with

the rest of the world and sliding into an anti-democratic mode of governance long

before the rise of the religious right and the neo-cons hastened this process.

When a group of fundamentally dishonest ideological extremists took control of

the presidency and the Congress, the corrupt condition of the U.S. political system

began to be revealed in all sorts of criminal acts.

The conclusions I draw from this are, first, that in Europe during two world

wars the United States seems not to have stooped to officially ordering the

torture and mistreatment of prisoners of war, though only because arrayed against

it were fighting forces that held U.S. prisoners and could retaliate. But in

three Asian-Pacific wars—against Japan, North Korea, and the peoples of

Indochina—the greater capabilities of U.S. forces made the fighting far

more one-sided. In World War II, victorious U.S. troops in the Pacific confronted

an enemy equipped with inferior weapons, usually took no prisoners, and often

mutilated and murdered the wounded with impunity. The Japanese army too mistreated

Allied prisoners and civilians on the battlefield and in occupied territories,

but they alone were held criminally accountable for their actions. Vietnam and

later interventions were unprovoked colonial wars against much weaker enemies.

When going against the weak, the U.S. military has invariably used torture tactics

on a wide scale.

Bush built on the legacy of war crimes and atrocities ordered by past presidents,

including his own father and Bill Clinton, both of whom had issued presidential

directives authorizing “extraordinary rendition.” In 2001 Bush expanded

this practice without furnishing any meaningful guidelines. He is not the first

president who ever turned his back on the fundamental principles that underpin

the international order; but he and his top officials are certainly the first

to have shattered the torture taboo while openly and repeatedly expressing contempt

for international law. They are also the first to threaten the use of nuclear

weapons even against non-nuclear states.

Today in the United States no strong public pressure exists for upholding the

laws against torture of persons considered “enemy.” In 2002 a poll

indicated “that one-third of Americans favored the use of torture on terrorist

suspects.” The most recent Gallup poll, released March 1, 2005, suggested

that 39 percent would support torturing “known terrorists if they know

details about future terrorist attacks.” Clearly a large minority, whose

views this Administration represents, believes that it is acceptable, if not

wholly justified, to employ the tactics of torture in the fight against terrorist

suspects in order to extract information that might save innocent lives. What

this surely reflects is the passionate denial of the educated classes that the

U.S. has been deeply involved in the gravest of international crimes.

To intentionally inflict pain and suffering on helpless detainees, whether

or not they engaged in combat, is illegal and morally wrong, besides being cowardly

and counterproductive. The legal prohibition on torture is absolute and unambiguous

and can never be justified under any conditions. The only problem is that the

U.S. government never actually ratified any humanitarian law without inserting

loopholes that would allow it to make a claim of exemption.

The best available evidence suggests that torturing defenseless captives to

obtain information doesn’t deter terrorist attacks. The information extracted

under White House and Pentagon torture policy has proven singularly ineffective

in defeating a popular resistance movement that has the support of the local

population. In Iraq, Bush policies have only succeeded in creating terrorists,

fueling the flames of resistance to the U.S. presence, and breaking up the coalition

of governments that unwisely sent troops to Iraq. Furthermore, the history of

modern warfare shows that guerilla resistance movements do not depend on hierarchical

chains of command that can be broken by such interrogation methods. To stop

their pain, prisoners will say anything, rendering what they say unreliable.

Secretary of State Colin Powell found this out when he delivered his infamous

address to the UN Security Council in February 2003, “which argued the

case for a preemptive war against Iraq.” In his speech, Powell drew on

the testimony of an unnamed “senior terrorist operative” who had

told his interrogators that Saddam Hussein had offered to train Al-Qaeda operatives

in the use of ‘chemical or biological weapons.’” After the

U.S. invasion, it turned out that the terrorist, one Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi,

had been tortured by his CIA and Egyptian interrogators. Later, at Guantanomo,

Libi recanted and admitted that he had lied. So much for evidence obtained through

torture and the spin master who relied on it to justify aggression.

U.S. leaders have been intent on controlling the world ever since the Truman

administration ended the war with Japan in a five-month orgy of conventional

bombing before destroying Hiroshima and Nagasaki with atomic bombs. Their greed,

ambition, and lack of foresight have left them with no solution but to pit themselves

against the nationalism and desire for self-determination of weaker states throughout

the world. Presidents and generals solved the problem of discovering who the

enemy is by defining the entire population as enemy. When the “enemy”

is the civilian population who won’t do our bidding, not only do the kill

ratios have to be high, but reliance on torture, murder, and assassination also

becomes vital. This is why Afghanistan and Iraq are in the same class as Korea

and Vietnam: imperialism produces the logic of torture.