Untitled Document

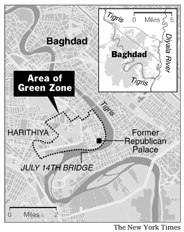

BAGHDAD, Iraq, July 4 - Iraqis call it Assur, the Fence. In English everyone calls

it the Wall, and in the past two years it has grown and grown until it has become

an almost continuous rampart, at least 10 miles in circumference, around the seat

of American power in Baghdad.

A barrier commonly known as the Wall surrounds the Green Zone.

The wall is not a small factor in the lives of ordinary Iraqis outside it. Khalid

Daoud, an employee at the Culture Ministry, still looks in disbelief at the

barrier of 12-foot-high, five-ton slabs that cuts through his garden.

A few months ago, he said, the American military arrived with a crane and tore

up the trees in his garden, smashed the low wall surrounding it, swung the slabs

into place and topped them with concertina wire.

Later they put up a 24-hour guard tower and a brilliant floodlight on the other

side. With their privacy gone, his wife and daughter must now tend the garden

in their abayas, or cloaks, and the family no longer sleeps outside when electricity

failures at night shut down the air conditioning.

"I feel like it's going to choke me," Mr. Daoud said of the wall.

This is one snapshot of life for countless Iraqis who live, work, shop and

kick soccer balls around in the shadow of the structure. Many despise the wall,

a few are strangely drawn to it, but no one can ignore it. Fortifications of

one kind or another abound in the city, but there is nothing that compares to

the snaking, zigzagging loop that is the wall.

Sometimes likened to the Berlin Wall by those who are not happy about its presence,

the structure cleanly divides the relative safety of the Green Zone that includes

Saddam Hussein's old palace and ministry complex, now used by the American authorities

and heavily patrolled by American troops, from the Red Zone - most of the rest

of Baghdad - where security ranges from adequate to nonexistent.

But for all the problems faced by residents across the city, the neighborhoods

within a few blocks of the wall have become a world apart. Mortar rounds and

rockets fired at the Green Zone fall short and land there. Suicide bombers,

unable to breach the wall, blow themselves up in shops just outside it. And

the maze of checkpoints, blocked streets and American armor may be thicker here

than anywhere else in Baghdad.

"We are the new Palestine," said Saman Abdel Aziz Rahman, owner of

the Serawan kebab restaurant, by the northern reaches of the wall.

Two weeks ago, a man walked into a restaurant near the Serawan and blew himself

up at lunchtime, killing 23 people, wounding 36 and sending pieces of flesh

all the way to Mr. Rahman's establishment.

Lt. Col. Steven A. Boylan, director of the main press information center in

Baghdad, said construction of the wall was guided by "an overall force

protection plan."

An American contractor, Kellogg Brown & Root, builds sections of the wall,

Colonel Boylan said. He said he was not sure how complaints about the wall were

handled. But whatever the official protocol, residents said it was no use trying

to slow the placement of the slabs.

Mr. Daoud, whose garden was ruined, said he had complained and had simply been

told that the city had approved the work and there was nothing he could do.

But one of the paradoxes of the wall is that while many are repelled by it,

others are drawn by the feeling that they will be protected by the overwhelming

might that lies just on the other side. American foot patrols, rarely seen elsewhere

in Baghdad, are fairly routine along the outside of the wall, and residents

know that any sustained guerrilla incursion near the zone would draw a swarm

of Apache helicopters and Humvees, as well as a tank or two if necessary.

"It's good and it's not good," said Abdul Kareem Jabbar, a government

employee whose backyard, swarming with clucking chickens and his extended family's

children, abuts the wall not far from the Serawan restaurant.

"What's good about it - it's a safe and secure area," Mr. Jabbar

said. "And what's bad about it," he said, pointing over his shoulder

toward the house next door, "a mortar fell over there the other day."

Other than that, the biggest nuisance Mr. Jabbar has faced is what he said

were empty liquor bottles tossed over from the Green Zone onto his family's

cars.

The stretch of wall near the Serawan, which is faced with a stucco- like material,

is not new. It is there that the wall encloses the Assassin's Gate, the bulky

arch above a boulevard leading to Mr. Hussein's former Republican Palace. Even

though the Americans doubled its height with a chain-link fence, barbed wire

and a green tarpaulin on top, there is little sense that the structure has blighted

the neighborhood.

Soad Harb, an engineer who lives next to the July 14th Bridge in an apartment

that senior officials in Mr. Hussein's government abandoned in 2003, said she

was happy to live so close to the southern boundary of the Green Zone, where

she sometimes finds work with Fluor, a big American contractor.

Ms. Harb said that while the American checkpoint at the end of the bridge made

the neighborhood dangerous and noisy, the soldiers who walked through the area

talking with children made the barrier seem less intimidating.

But the same cannot be said in the middle-class district of Harithiya, just

beyond the western edge of the Green Zone, where the concrete slabs arrived

about two months ago.

Sometimes called T-walls because they splay outward at their base to form a

pedestal, and sometimes called blast walls because the steel reinforcing inside

is designed to withstand explosions, the slabs are a looming, sinister presence

facing a long line of family homes from across Al Shawaf Street in Harithiya.

Haider al-Shawaf, a 35-year-old businessman who grew up here, first described

the unpleasantness of the wall with a crude American expression. Then, as helicopters

clattered to and fro overhead, Mr. Shawaf said nervously, "I am afraid

of the Americans here - afraid of this wall."

Boys and young men playing soccer in a dusty field nearby echoed that thought.

"There are seven teams in Harithiya," said Faddal Munder, 21, who

wore a bright orange jersey. "Four teams are afraid to come here to play

because it's next to the walls."

There are also places where the wall passes through grim uninhabited places,

like the wasteland along the bank of the Tigris on the eastern side of the Green

Zone. The wall - or walls, since they sometimes form a double line - follow

the contours of the terrain like the parapets of some medieval castle, seemingly

with the aim of thwarting an insurgent amphibious attack.

But it is in the city's neighborhoods that the wall, so important to the security

of Americans and the Iraqis who work with them, also cuts with such ease through

the hearts and the thoroughfares of everyday citizens.

"It was very nice street," Mr. Shawaf said with the dismay of someone

who loves his tiny corner of the urban plan. "It was very nice street."