Untitled Document

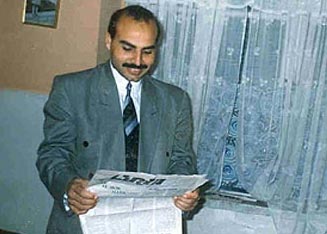

Osama Moustafa Hassan Nasr

MILAN, Italy -- Among the multiple mysteries swirling around the abduction of

Osama Moustafa Hassan Nasr in Italy, one stands out as by far the most perplexing.

Why would the U.S. government go to elaborate lengths to seize a 39-year-old

Egyptian who, according to former Albanian intelligence officials, was once

the CIA's most productive source of information within the tightly knit group

of Islamic fundamentalists living in exile in Albania?

Neither the Bush administration nor the CIA has acknowledged any role in the

operation. But U.S. government officials privately paint Nasr, better known

as Abu Omar, as a dangerous terrorist who once plotted to kill the Egyptian

foreign minister and was worthy of an audacious daylight abduction involving

more than 20 operatives, weeks of planning and hundreds of thousands of dollars.

One senior U.S. official, who spoke on condition that she not be identified,

asserted: "The world's a better place with this guy off the streets."

But evidence gathered by prosecutors here, who have charged 13 CIA operatives

with Abu Omar's kidnapping, indicates that the abduction was a bold attempt

to turn him back into the informer he once was.

As a result, Italian-American relations are at their lowest point in years,

13 Americans are fugitives from Italian justice, and Milanese prosecutors and

police, who had been closely monitoring Abu Omar and knew nothing about his

planned abduction, are furious.

"Instead of having an investigation against terrorists, we are investigating

this CIA kidnapping," a senior prosecution official fumed last week.

According to the prosecutor's application for the 13 warrants, when Abu Omar

reached Cairo on a CIA-chartered aircraft, he was taken straight to the Egyptian

interior minister.

If he agreed to inform for the Egyptian intelligence service, Abu Omar "would

have been set free and accompanied back to Italy," the document said.

Alternatively, the senior official said, the Americans may have hoped the Egyptians

could learn something by interrogating Abu Omar about planned resistance to

the impending war on Iraq.

Abu Omar refused to inform, according to the document, and spent the next 14

months in an Egyptian prison facing "terrible tortures." After a brief

release in April 2004, he was imprisoned again.

The source of the prosecution's information is Mohammed Reda, another Egyptian

imam living in Milan and one of the first people Abu Omar called during his

brief release.

Asked to assess Reda's credibility, the prosecution official asserted that

"in this case, he had no reason to lie. And when he made his first statements,

he was unaware he was being intercepted" by a police wiretap on his cell

phone.

Abu Omar was first offered a chance to inform in Albania in 1995. According

to former officials of ShIK, the Albanian National Intelligence Service, he

was far from reluctant.

At the behest of the CIA, ShIK had created an anti-terrorist unit that, former

ShIK officials said, was essentially an arm of the CIA.

In those years, the Albanian government, increasingly worried that it might

be playing host to Islamic terrorists, accorded the CIA far more leeway than

most other countries to operate within its borders.

CIA officer's role

The real boss of the anti-terror squad, according to its former second-ranking

official, Astrit Nasufi, was a CIA officer known as Mike who worked in the American

Embassy in Tirana, the Albanian capital.

Mike, who spoke fluent Arabic, set up the ShIK unit's office and taught Nasufi

and the dozen or so other ShIK operatives about Islamic terrorism, how to conduct

interviews and how to monitor suspects.

The CIA even provided the badly paid ShIK agents with better clothes and food

for their families, Nasufi said.

The ShIK agents came to idolize Mike, who according to Nasufi was killed in

a car crash in the U.S. in 1996 after completing his Albanian assignment. When

the ShIK agents later visited the CIA in Virginia for a training course, they

visited Mike's grave at Arlington. Until they saw the headstone, they hadn't

known his last name.

ShIK sprang into action in August 1995, when the Egyptian foreign minister,

Amr Moussa, visited Albania. There was no evidence that an assassination plot

against Moussa was in the works. But two months before, exiled Egyptian fundamentalists

had tried to kill Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak during Mubarak's visit to

Ethiopia.

Nasufi and Flamur Gjymisha, the chief of ShIK's First Intelligence Directorate,

said Mike told ShIK to detain a dozen or so Egyptians living in Tirana who might

pose a threat to Moussa.

A few days before Moussa's arrival, ShIK got the pickup list. It included seven

or eight members of Jamaat al Islamiya ("The Islamic Group") and a

few from another Egyptian exile group, the Islamic Jihad, which later merged

with Al Qaeda.

Nasufi said Abu Omar, an Egyptian, had been living in Albania for four years

and working for a Muslim charity, the Human Relief and Construction Agency (HRCA).

His name was not on the pickup list, Nasufi said, because "no previous

suspicion" had been attached to him, and he had never been mentioned in

the CIA's requests for information about individuals in Tirana.

The CIA also gave ShIK the license plates of four cars, including a dark green

Land Rover that allegedly belonged to the HRCA. "We started looking for

the cars on Aug. 27 in the morning," recalled Nasufi.

By midafternoon they had found the Land Rover in a parking lot near the former

Institute for Physical Education. When ShIK checked the registration, the person

listed as responsible for the vehicle was Osama Nasr--Abu Omar.

According to Nasufi, the Land Rover looked like it hadn't been driven for months.

Nevertheless, two CIA operatives arrived from the U.S. and checked the vehicle

for any trace of explosives. Nothing was found, Nasufi said, but the CIA told

ShIK to pick up Abu Omar anyway.

Around 10 p.m. on Aug. 27, Albanian police showed up at Abu Omar's Tirana apartment

and led him away. He was held for about 10 days, Nasufi said.

What was essentially an accidental arrest proved to be a great coup for ShIK

and its CIA overseers.

Abu Omar was taken to the main police station for interrogation by Nasufi and

another ShIK agent, Ferdinand Nuku. Nasufi described Abu Omar as "smooth

and calm, probably because he wasn't under pressure from us. He was never aggressive

with us. We didn't use a lot of physical pressure on him. He was well-behaved

and gentle."

At first Abu Omar refused to talk, then abruptly changed his mind. "After

a week, we had a full file," said Nasufi, who doesn't remember Abu Omar

as a particularly zealous Muslim, recalling that he interrupted the interviews

to pray only twice in 10 days.

To ShIK, Abu Omar admitted he had fled Egypt because he belonged to Jamaat

al Islamiya, and that Jamaat had about 10 people working for three Islamic charities

in Albania, including Al-Haramain Islamic Foundation and the Revival of Islamic

Heritage Society.

Since Sept. 11, 2001, some offices of both of those charities have been labeled

terrorist supporters by the Bush administration.

Abu Omar told the ShIK agents that, for Jamaat members like himself, Albania

was a "safe hotel"--a country where fundamentalist Muslims believed

they could live without fear of political repression.

For that reason, Abu Omar insisted, the Jamaat members in Albania had no plans

to kill Amr Moussa. Such a move would have cost Jamaat its haven, Abu Omar explained.

Abu Omar was the first Arab willing to inform for ShIK, and ShIK was amazed

by its good fortune. So, Nasufi said, was the CIA. After each interview, Nuku

gave handwritten notes to the U.S. Embassy's new CIA representative, "Francis,"

who had replaced "Mike."

"It was the first case that we provided the Americans with totally independent

information," Nasufi said. "We became a main player for the first

time. We weren't just tools. We gave them a clear idea of who was monitoring

the U.S. Embassy for [Jamaat], who was coming in and out of the country."

At the time, the CIA in the Balkans was primarily interested in keeping tabs

on the former mujahedeen joining the Bosnian Muslims in their struggle against

Serbia and Croatia.

The CIA, Nasufi said, lauded ShIK for its intelligence coup.

Nasufi said Abu Omar was believed to be credible. Of the 100 or so items of

information he offered, 20 or 30 were confirmed by information ShIK received

from the CIA.

After Abu Omar was allowed to return home, the collaboration deepened. He talked

to ShIK about Jamaat branches in the United Kingdom, Germany and Italy--including

Milan, where Jamaat had close relations with the Institute for Islamic Studies

on Via Quaranta.

ShIK had a strict rule against offering money to informers, Nasufi said, but

ShIK did offer Abu Omar help in mediating a dispute with the landlord of the

bakery he had just opened, and smoothing out problems with his residence permit

that had arisen from his marriage to an Albanian, Marsela Glina.

Abu Omar gratefully accepted ShIK's help, Nasufi said. But a few weeks after

he began collaborating with ShIK, Abu Omar, Marsela and their daughter Sara

suddenly left Albania.

Hasty departure

Abu Omar's hasty departure struck ShIK as odd, Nasufi recalled, because the

Egyptian had seemed so willing to cooperate and had appeared happy that ShIK

was offering him assistance with his problems. When Flamur Gjymisha asked Ferdinand

Nuku what had happened to Abu Omar, Nuku said the CIA had told him Abu Omar

was living in Germany.

Abu Omar, without his Albanian family, surfaced again in Rome in 1997, where

he was accorded political refugee status. Moving north to Milan, he gravitated

to the Islamic institute on Via Quaranta, which has a reputation as the most

radical Islamic outpost in Italy.

There Abu Omar preached fiery sermons and served for a time as the deputy chief

imam. After the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks led to the U.S.-led coalition's military

offensive in Afghanistan, his sermons grew even more hostile toward the U.S.

According to what the police were hearing on his telephone, Abu Omar also was

helping recruit Muslims to fight against the coalition in Afghanistan.

A Milan magistrate recently ruled in an unrelated case that recruiting fighters

for foreign battles is not illegal under Italy's anti-terrorist laws. Nor, it

seems, did the police have much evidence that Abu Omar had been plotting terrorist

attacks.

When Milan prosecutors applied for an arrest warrant for Abu Omar, the only

charges listed were "association with terrorists," aiding the preparation

of false documents and abetting illegal immigration.

Although police had grounds for Abu Omar's arrest, the tap on his phone and

the microphones hidden in his apartment and the Via Quaranta mosque made him

far more valuable as a window into the comings and goings of other jihadists.

"When you find an important member of an organization," the senior

prosecution official said, "you don't arrest him immediately, you follow

him. When Nasr disappeared in February [2003], our investigation came to a standstill."

What mystified the Italian authorities was why the CIA would want to take Abu

Omar out of circulation--especially since they were sharing with the CIA the

fruits of their electronic surveillance of Abu Omar--and why the Egyptians would

want him back.

Some American officials maintain Abu Omar's abduction was necessary because

of his suspected involvement in a plot to bomb a bus that carried the children

of foreign diplomats attending the American School of Milan.

But the senior prosecution official said, "I have never seen any evidence.

I don't think there was a bomb plot against the American School."

Indeed, a conversation recorded by police on April 24, 2002, about eight months

before his abduction, appears to portray Abu Omar as something of a force for

moderation.

When an unidentified Egyptian man says he wants to attack "all establishments

or Israeli interests . . . anything that belongs to the Jews, in all the world,"

Abu Omar tells him, with a laugh, "Use your head!"

On June 6, Abu Omar is overheard speaking with an unidentified South African

man who seems to be talking about car bombs.

"Who has made them?" Abu Omar asks. "Who? Who?"

"One of the Palestinian brothers," replies the South African.

"The Palestinian?" Abu Omar asks.

"Yes," the man answers. "The one who is called the machine .

. . the one who is in Albania."

After a pause, Abu Omar replies, "No, no, the car is not the proper tool.

We don't need the car. . . . "

FROM THE STREETS OF MILAN TO AN EGYPTIAN PRISON

An Italian prosecutor has asked the U.S. to extradite more than a dozen CIA

operatives accused of kidnapping a man in Milan, Italy, and transporting him

to Egypt.

SEQUENCE OF EVENTS

According to Italian prosecutors

M I L A N , I T A L Y

(street map)

1. Feb. 17, 2003 {bull} Around noon

Osama Nasr, also known as Abu Omar, leaves his Milan

apartment and begins walking toward a local mosque.

- Position of lookout(s) in abduction team (based on cell phone records)

VIA CONTE VERDE

Abu Omar walks toward a local mosque

Shortly after noon

He is stopped on the street by two men he later describes as

speaking "bad Italian." By one passerby's account, they spray a

chemical in his face, then hustle him inside a parked white van,

which drives away at high speed followed by at least one

and possibly two chase cars.

2. 5 p.m.

The van arrives at a U.S.-Italian air base at Aviano, Italy.

6:20 p.m.

A Learjet with Abu Omar aboard departs Aviano for Ramstein,

Germany.

3. 7:30 p.m.

The Learjet lands at a U.S. air base in Ramstein, where Abu Omar is transferred

to a Gulfstream jet.

8:31 p.m.

The Gulfstream departs Ramstein bound for Cairo.

4. Feb. 18 {bull} Early morning

Abu Omar arrives in Cairo and is taken into custody by Egyptian

authorities.