Untitled Document

|

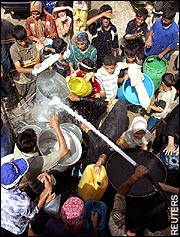

People gather to collect water

at an emergency pump |

Lubna Ali was resigned to the daily electricity shortages that cut off the lights,

shut down the air conditioning and left her family sweltering in the summer heat.

She coped with her terror of the bombs, drive-by shootings and kidnappings

by deciding, at the start of this year, to venture no further than her garden

gate.

But the final straw for the 42-year-old housewife from the middle-class New Baghdad

district in the Iraqi capital came when a rebel attack on a water plant cut off

supplies to two million people.

With the temperature above 50C, this brought Mrs Ali "the true knowledge

of despair".

"I didn't think it could get worse - and then it did," she said,

her kitchen filled with dirty plates and the lavatories unflushed. "The

children are crying. All we want is to pour some water on our bodies.

"I now wish we could go back to Saddam's time. We suffered then, but not

like the suffering nowadays. There is no water or electricity. I can't sleep

because of the heat. How are we to live these lives of misery?"

At a conference in Brussels this week, the Iraqi government briefed representatives

from more than 80 countries and organisations on its programmes to rebuild the

county, and listed its achievements.

In Baghdad, meanwhile, crowds of thirsty people waited for hours at emergency

water pipes to fill jerry cans and buckets, while women washed clothes in the

dirty waters of the Euphrates.

The citizens of this city do not give up easily. The shock, fear and chaos

that came with the American takeover was soon replaced by black humour and stoicism.

Outsiders are invariably astounded at how - after yet another bombing - street

vendors can reopen their stalls, even as the bloodstains are being hosed from

the pavements.

But the mood in the city is increasingly one of desperation. While residents

wait in vain for promised reconstruction projects to materialise, the government

cannot even agree on the make-up of the committee to draw up a new constitution,

let alone its contents.

Sovereignty was returned to the Iraqi people from the occupying administration

a year ago. But electricity output in the capital has decreased in the past

five months - averaging only 854 megawatts per day now, compared with 2,500

megawatts before the war. The rationing system for sugar and baby milk collapsed

at the beginning of the year, forcing many to go without.

Sadr City, the vast slum in the capital's west, is in the grip of a hepatitis

outbreak. Forty per cent of Baghdad's homes have reported sewage on the streets.

Fresh water had finally returned to most of the city by last night - but for

only two hours a day.

And then there are the suicide bombers. After a brief lull earlier this month,

when the Iraqi army launched Operation Lightning to root out insurgents in the

city and made more than 1,000 arrests, they resumed their deadly work as usual

last week.

Shortly after dawn on Thursday, four bombs exploded in Karada, a district known

for its teashops and clothing stores, killing 15 people, only hours after three

other blasts had torn through the Shula neighbourhood.

At one bomb scene, the mangled chassis of a car hung from a tree and the blue

tiles were stripped from an adjacent mosque. Masked Iraqi police moved in, bringing

central Baghdad traffic to a standstill for 90 minutes.

Standing beside a pool of blood, Abu Radhi, an architect, said: "This

city was once the most beautiful in the Middle East. People would stroll by

the river at dusk and the restaurants were filled with laughter. Now our life

is this."