Untitled Document

This article is adapted from a talk that Caltech vice provost and professor

of physics and applied physics David Goodstein presented at an April 29 program

of the Institute support group, the Caltech Associates. Goodstein’s new

book, Out

of Gas: The End of the Age of Oil, was published in February by W. W. Norton.

On December 5, the New York Times Book Review named Out of Gas one of its 100

Notable Books of the Year.

In the 1950s, it was not Saudi Arabia but the United States that was the world’s

greatest producer of oil. Much of our military and industrial might grew out

of our giant oil industry, and most people in the oil business thought that

this bonanza would go on forever. But there was one gentleman who knew better.

He was an oil exploration geologist named Marion King Hubbert.

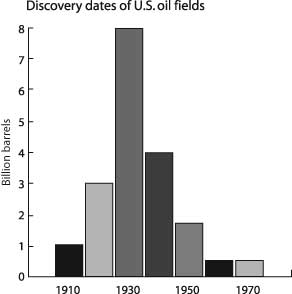

In about 1950, Hubbert realized that the trajectory of oil discovery in the

continental United States was going to be a classic bell-shaped curve, for the

decades from 1910 to 1970, in billions of barrels per year (see figure 1, below).

He also saw that there would be a second bell-shaped curve that would represent

production, or consumption, or extraction. The oil industry likes to call it

“production,” but the industry doesn’t really produce any

oil at all. It does, however, reflect the rate at which we use the oil up. Perhaps

you could call it supply.

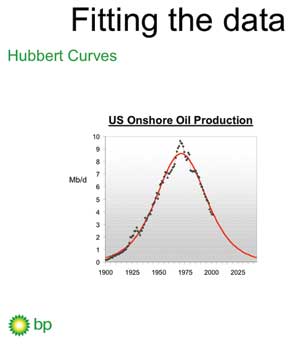

Hubbert realized that using what he knew in 1950 about the history of discoveries,

along with what was already known about consumption, and a little mathematics,

he should be able to predict that second bell-shaped curve. And so he did (see

figure 2, below). The red, bell-shaped curve is the kind of curve he predicted.

The black points are the actual historical data, and the uppermost point represents

what has come to be known as Hubbert’s Peak. Obviously, he was doing something

right.

© BP

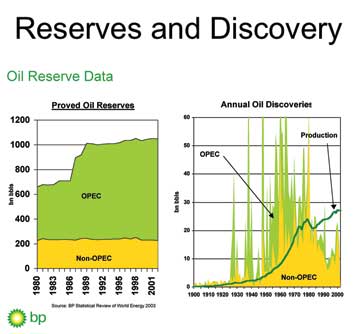

The situation worldwide is a little less well-determined. A third graphic provided

by the energy conglomerate BP, shows what the world’s known crude oil

reserves are (see figure 3, left-hand graph, below). The amount that we have

now is a trillion barrels of oil. So people in the industry might say, we have

a trillion barrels just sitting there waiting to be pumped out of the ground;

we’re using it up at a rate of about 25 billion barrels a year, and so

we have 40 more years to go—there’s nothing to worry about. But

as Hubbert has shown us, that’s the wrong way of looking at it .

© BP

Before we leave that curve, though, I want to point out that a sudden jump

of 300–400 billion barrels of oil in OPEC (the Organization of the Petroleum

Exporting Countries) reserves occurs in the late 1980s (see figure 3, left-hand

graph, above). But there were no significant discoveries of oil in OPEC countries

during that period. What happened instead is that OPEC changed its quota for

how much each country could pump on the basis of what it claimed in reserves,

and politicians discovered 400 billion barrels of oil without ever drilling

a hole in the ground! This helps us to understand how undependable these numbers

are for worldwide proven oil reserves.

As you can see, the curve that traces the historic record of oil discovery

peaks around 1960. In other words, Hubbert’s peak for oil discovery came

and went 40 years ago.

The curve for oil usage, as you can see, is a rising curve and will become

a bell-shaped curve eventually. Note that for the last quarter century, we’ve

been using oil faster than we have been discovering it. World reserves should

have decreased during that time by about 200 billion barrels. Instead, as we’ve

seen, they’ve increased by 400 billion barrels. In any case, it should

be possible, given this much information, to make a prediction similar to the

one that Hubbert made for the continental United States for worldwide oil production.

One such estimate was published in 1998 in Scientific American. It

predicts that we will have a worldwide maximum in oil production just about

now—around the middle of the decade 2000–2010. What will

happen when we reach that peak we don’t really know. But we had a foretaste

in 1973 and ’79 when the OPEC countries took advantage of the supply shortage

in the United States and shut down the valve a bit. What happened, as you may

recall, is that we had instant panic and despair for the future of our way of

life, and mile-long lines at gas stations.

We don’t know what’s going to happen at the next peak, but we do

know that those past peaks were artificial and temporary. The next one will

not be artificial and it will not be temporary.

However, we have to use caution in evaluating these types of predictions. One

crucial quantity that goes into making such an estimate is knowing how much

oil Mother Nature originally made for us—that is, how much oil was in

the ground before we ever started pumping it. The Scientific American estimate

used 1.8 trillion barrels of oil as the baseline number. Today it looks like

2.1–2.2 trillion barrels might be more accurate. That number—the

total amount of oil that ever existed—tends to increase with time for

a variety of reasons.

First, new technology and new discoveries have exactly the same effect—they

both make more oil available. Secondly, as oil becomes scarcer and the price

goes up, more oil becomes available at the increased price, because you can

invest more capital into pulling it out of the ground. And finally, these estimates

depend to some extent on those proven reserve numbers and, as we’ve already

seen, those numbers are not very reliable. Nevertheless, the central idea of

the Hubbert Curve is certainly correct: the supply of any natural resource invariably

rises from zero to a maximum point, and then it falls forever. Oil will behave

in the same way.

In 1997, Kenneth Deffeyes, a former Shell Oil geologist who’s now an

emeritus professor of geosciences at Princeton, published a book he entitled

Hubbert’s Peak—The Impending World Oil Shortage. In it, Deffeyes

said he knew that Hubbert had been right and that the peak for domestic production

had been reached when he saw this sentence in 1971 in the San Francisco Chronicle:

“The Texas Railroad Commission announced a 100% allowable for next month.”

To demystify that sentence, the Texas Railroad Commission was the quaintly

named cartel that controlled the U.S. oil industry by making strategic use of

the excess capacity for pumping in Texas. When the commission said, “100%

allowable for next month,” it meant that there was no longer any excess

capacity. They were pumping flat-out, and therefore Hubbert’s Peak had

been reached.

Ever since reading this, I’ve thought that the signal that the worldwide

peak had been reached would be when we found out that Saudi Arabian production

had peaked. For the last few decades, the Saudis have been using excess pumping

capacity to manipulate the world oil market in exactly the same way the Texans

once did.

Well, on February 24 of this year, a story appeared on the front page of the

New York Times entitled “Forecast of Rising Oil Demand Challenges Tired

Saudi Fields.” Among other things, the article said that Saudi Arabia’s

oil fields are in decline, prompting industry and government officials to raise

serious questions about whether the kingdom will be able to satisfy the world’s

thirst for oil in the coming years.

This is a New York Times story, so it’s very long, as many Times stories

are, and it’s written in a style in which each successive paragraph is

contradicted by the next paragraph. This is called “balanced reporting.”

Sure enough, much farther down in the article, we find these words: “Some

economists are optimistic that if oil prices rise high enough, advanced recovery

techniques will be applied, averting supply problems.” But here comes

the contradiction in the next paragraph, “But, privately, some Saudi oil

officials are less sanguine.”

I don’t know whether we will look back years from now and say that this

was the beginning of the end of the age of oil. We’re much too close to

it to tell, and our figures are, overall, much too uncertain. But, to those

people who are aware of the Hubbert’s Peak predictions, as the writer

of this article apparently was not, this was a chilling report.

Economists tell us that there can never be a gap between supply and demand

because the process is regulated by price. That’s never been true in the

case of oil, because it has always been controlled by cartels, first in Texas

and later by OPEC. However, once the peak occurs, OPEC will lose control of

the situation, and the price mechanism will kick in with a vengeance. But the

supply can keep up with the price only if there is something to supply.

I’m sometimes asked, what about replenishing our oil reserves through

deep-ocean exploration? I’m already factoring in close-to-shore oil production,

but the deep oceans are essentially unexplored and, it’s true, we don’t

know whether there’s any oil out there. Over the last hundreds of millions

of years, oil typically has been manufactured in places that are rich in life,

which deep oceans are not. But the landmasses have moved around over geologic

time, so there may be deep-ocean oil reserves.

Even so, deep oceans are technically extremely difficult places to drill for

oil. That leaves us with only two remaining reservoirs—the South China

Sea, which currently has seven countries claiming mineral rights to it; and

Siberia, which has very bad access problems. And those resources, of course,

are finite also. So let’s see what else there is to use, aside from oil.

The word “oil” covers more than just the conventional light crude

that we’ve been pumping up to now. It also covers heavy oil, oil sands,

and tar sands. Heavy oil is essentially what’s left behind in the field

after you pump the light crude away. And, of course, if you put more money in—that’s

the price mechanism—you can usually squeeze a little more oil out of any

field. But it’s both more costly and more time-consuming to get that oil

out. And the more you pump out, the heavier it gets.

Natural gas could be a very good substitute for oil. Cars that are not very

different from those we drive today can run on compressed natural gas, and it’s

a particularly clean-burning fuel. But if we turn to natural gas in a major

way to replace diminishing supplies of oil, it will only be a temporary solution.

The Hubbert Peak for natural gas is only a decade or so behind Hubbert’s

Peak for oil.

Oil was created when so-called source rock, full of organic inclusions, sank

deep within the earth. The inside of the earth is heated by natural radioactivity,

and the deeper you go, the hotter it gets. This source rock sank just deep enough

into the heated interior for the organic matter to get cooked into oil. Rock

that sank deeper got overcooked and became natural gas. Rock that sank to a

more shallow level became shale oil, which is essentially unborn oil that can

be made into a fuel by strip-mining, crushing, and heating the rocks until you

generate a usable liquid. People who have invested many millions of dollars

into trying to exploit this resource have come to the conclusion that it will

probably always be energy-negative, meaning that you will always have to put

more energy into acquiring and processing it than you will ever get out of it.

Methane hydrate is a solid that looks like ice, but that burns if you ignite

it. It consists of methane trapped in a sort of cage of water molecules and

it gets created when methane comes into contact with water under very high pressure

at very low temperatures close to the freezing point of water. Nobody has any

idea of where all it is, how much there is, whether it can be mined, or how

it could be used—all we know is that this stuff exists.

Finally, there is coal. We are told that there is enough coal in the ground

for hundreds, maybe even thousands of years, at the present rate of use. The

fact that these estimates range over a factor of ten tells you immediately that

nobody has the foggiest notion of how much coal is actually available. But even

those projections might be considered reliable, compared to the second part

of that optimistic sentence: “at the present rate of use”! We’ll

get to that in a moment.

The largest coal deposits are in the United States, and China and Russia have

very large reserves as well. Coal can be liquefied and made into a substitute

for oil. That was done in Nazi Germany during World War II, and in South Africa

under apartheid. That alone should tell you that you have to be fairly desperate

to do it, but it can be done.

But, coal is a dirty, dirty fuel. It often comes with nasty impurities, including

mercury, arsenic, and sulfur. The mercury that accumulates in the bodies of

tuna or swordfish—and which has led to FDA warnings to limit our consumption

of these fish—originates in coal-fired power plants in the United States.

We use now about twice as much energy from oil as we do from coal, so if you

wanted to mine enough coal to replace the missing oil, you’d have to mine

it at a much higher rate, not only to replace the oil, but also because the

conversion process to oil is extremely inefficient. You’d have to mine

it at levels at least five times beyond those we mine now—a coal-mining

industry on an absolutely unimaginable scale.

And even that doesn’t take into account the world’s increasing

population, or the fact that nations like China and India want to have a higher

standard of living, which means burning more energy. Finally, it doesn’t

take into account the Hubbert’s Peak effect, which is just as valid for

coal as it is for oil. Long before we have mined the last ton, we will have

started to deplete our ability to get the stuff out of the ground. So, it’s

a very good bet that the governing “rate of use” number I mentioned

earlier is not hundreds or thousands of years, and that no more than one-tenth

of that timeframe represents a realistic estimate.

What all this suggests is that if we accept the economists’ solution

and just let the marketplace do its thing as we make use of all the fossil fuel

we can, we’ll start running out of all fossil fuels by the end of this

century.

So, what does the future hold? Well, for one thing, there will be an

oil crisis very soon. Whether that means it has already begun or won’t

happen until later in this decade or sometime in the next decade, I don’t

know. In my view, the numbers are not dependable enough for us to say.

However, while the difference between those estimates may be very important

to us, it’s of no importance at all on the timescale of human history.

Either we, our children, or perhaps our grandchildren, are in for some very,

very bad times. If we turn to all the other fossil fuels and burn them

up as fast as we can, they will all probably start to run out by the end of

the 21st century. Assuming that our planet remains habitable after such a vast

consumption binge, we will have to invent a way to live without fossil fuels.

(See sidebar “Too Hot To Handle?”)

How about hydrogen? Both President Bush and California governor Schwarzenegger

have publicly embraced hydrogen as a solution to our fuel problems. But there

are only two commercially viable ways of making hydrogen. One is to

make it out of methane, which is a fossil fuel. The other is to use fossil fuel

to generate the electricity that you need to electrolyze water and get hydrogen.

The economics of doing that are such that you end up using the equivalent of

six gallons of gasoline to make enough hydrogen to replace one gallon of gasoline.

So this solution is not a winner in the short run. In the long run,

if the problem of harnessing thermonuclear fusion can be solved and we have

more power than we know what to do with, you could use that form of energy to

make hydrogen for mobile fuel. I’ll get to that a little later.

There is also wind power, which many now see as a viable energy alternative.

And it is, but only to a limited extent. In regions like northern Europe, where

fossil fuels are very expensive and the wind is really strong, wind power will

someday come to rival hydroelectric power as a source of energy. But there are

relatively few places on earth where the wind blows strongly and steadily enough

for it to be a dependable energy source, and people don’t really like

wind farms—they’re ugly and they’re noisy. Wind power

will always be a part of the solution. But it’s not a magic bullet. It’s

not going to save us.

In recent years, the debate over nuclear power has revived, with proponents

maintaining that we can find environmentally sound and politically acceptable

ways to deal with the waste and security hazards. But even assuming that to

be true, the potential is limited. To produce enough nuclear power to equal

the power we currently get from fossil fuels, you would have to build 10,000

of the largest possible nuclear power plants. That’s a huge, probably

nonviable initiative, and at that burn rate, our known reserves of uranium would

last only for 10 or 20 years.

As things stand today, the only possible substitutes for our fossil-fuel

dependency are light from the sun and nuclear energy. Developing a way of running

a civilization like ours on those resources is an enormous challenge. A great

deal of it is social and political—we’re in the midst of a presidential

election, and have you heard either party say a word about this extremely important

subject? But there are also huge technical problems to be solved. So,

you might well ask, what can Caltech do to help?

The ultimate solution to our energy problem would be to master the power of

controlled thermonuclear fusion, which we’ve been talking about doing

for more than half a century. The solution has been 25 years away for the past

50 years, and it is still 25 years away. Beyond those sobering statistics, there

are at least five or six schemes for harnessing fusion energy that I know of.

One of them, called the spheromak, is studied here at Caltech in an experimental

program run by Professor of Applied Physics Paul Bellan and his research group.

In the spheromak, electric currents flowing in a hot ionized gas—otherwise

known as a plasma-—interact with magnetic fields embedded in the plasma.

As these fields and currents push the plasma around, new fields

and currents are created. There’s a sort of self-organizing interaction

occurring. You can see in this sequence of snapshots below, starting from the

top, that the plasma is organizing itself into a jet and then a kink develops

in the jet. This is something that happens all by itself, and it’s not

something that happens only occasionally—the gas always self-organizes

like that. After the kink develops, it breaks away from the body of the jet

as a doughnut. If you can find a way to maintain that doughnut and keep it going—that

is to pump in enough energy to keep it from decaying—the doughnut has

the perfect geometry required for containing a hot plasma undergoing thermonuclear

fusion.

Fusion research at Caltech.

But attaining this objective is far off. The existing apparatus is much too

small to reach the hundred million degree temperatures needed to generate power.

The Bellan team is studying the fundamental physics of the self-organizing process

in the hope it can be used to create and sustain the desired fusion plasma confinement

geometry in a reliable, controlled manner.

There’s another group at Caltech whose efforts are aimed largely at the

other alternative—solar energy. Their program is called Power the Planet:

Caltech Center for Sustainable Energy Research. Members include applied physicist

Harry Atwater, chemists Harry Gray, Nathan Lewis, and Jonas Peters, and materials

scientist Sossina Haile.

Furthermore, our former provost Steve Koonin recently stepped down from the

provostship and took a leave of absence from the Caltech physics faculty to

become chief scientist at BP. BP, formerly British Petroleum, is one of the

largest energy companies in the world, and so he now has one of the most important

energy positions in the world.

The fact that these and similar scientific and technical efforts are under

way at Caltech and elsewhere are encouraging, but they are not enough. What

we really need is leadership with the courage and vision to talk to us as John

F. Kennedy did in 1960, when he pledged to put a man on the moon by the end

of the decade. It’s the same kind of problem. We understand the basic

underlying scientific principles, but we have huge technical problems to overcome.

If our leaders were to say to the scientific and technical community,

“We will give you the resources, and you—right now, even before

it becomes imperative—will find a way to kick the fossil-fuel habit,”

I think that it could be done. But we have to have the political leadership

to make it work.