Entered into the database on Monday, June 13th, 2005 @ 15:26:07 MST

They know your favourite brand of whisky and how many cars are parked in your

drive. They know what time you leave work and where you buy your petrol. If pressed,

they can predict where you will go on holiday, how you vote and what fragrance

you like. We have become a nation of "glass consumers" - every detail of our spending

habits has become transparent to those organisations who keep tabs on us. Everything

we do, everywhere we go, leaves a trail. No one knows how many marketing lists are circulating in Britain, packed with

trivial and not-so-trivial details of our likes, dislikes, income and lifestyle.

But the electronic personal information industry is booming - and last year

was worth £2 billion. Marketers argue that the mountain of information

held on each of us is for our own good. It ensures that we can be targeted with

the goods and services we really want. But consumer and civil rights groups are increasingly worried that it is also

being used to discriminate and exclude. And when the information is wrong, it

can stop people getting credit cards, services or even jobs. Concerns about the threat to our identity and privacy from the explosion of

the personal information economy are raised in a new book, The Glass Consumer,

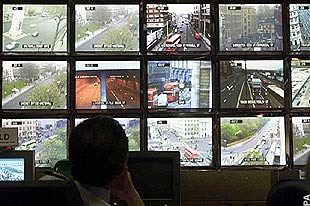

published this week by the National Consumer Council. Traditionally, concerns about privacy have concentrated on the intrusions justified

as being essential for combating terrorism, crime or anti-social behaviour.

The Government wants all drivers to carry a compulsory satellite tracking device

in their cars. The European Commission wants mobile phone companies and internet

service providers to keep details about every website visited for three years. Security agencies can track most people to within a few hundred feet of their

mobile phones, which work by revealing their locations to the phone networks.

If you haven't got a phone, the trail of credit and debit cards will reveal

where you've been recently. But, according to the NCC, the erosion of privacy from the personal information

industry is just as concerning. Susanne Lace, author of The Glass Consumer,

says most people are unaware how much information is held about them by marketing

companies. "Allusions to Big Brother scrutiny are becoming dated. Instead, we are

now moving towards a society of little brothers," she says. We've got a file on you Details of every economically active adult in the developing world are thought

to be stored on just 700 major databases. You've probably never heard of the

company Experian - but they've almost certainly heard about you. The company

has details of 45 million people in Britain and is one of the three main credit

reference agencies. Around 16 million of us have filled in one of Experian's detailed lifestyle

surveys - its booklets are sent through the post with questions about our income,

insurance policies, hobbies, favourite music and reading habits. The information collected by Experian and the other market research companies

from postal surveys is combined with data from credit-card applications, mail-order

shopping firms and online surveys to create specialist lists of customers: such

as single men aged 35 to 45 who like flashy cars, or women in their sixties

with big gardens. Data also comes from the state. Since 1981, information from the Census has

been released to businesses, and has been used to create postcode profiles which

are used by at least 500 of the UK's call centres, and which can pinpoint the

streets where the richest and poorest people live. Calls to banks and retailers

from people living in areas perceived as wealthy are put through immediately

to the best-spoken, best-trained and most courteous sales staff. Callers from

less affluent postcodes can find themselves pushed to the bottom of the queue,

where they wait in automated-voice hell. Other sources of information are more unexpected. Computers store "cookies",

which reveal to any website what you have bought from other online stores. Then

there are the supermarket loyalty card schemes, pioneered by Tesco in the 1990s,

which record every single item you buy. Thanks to the cards, supermarkets know

more about your shopping habits than you do - what days you shop, how swayed

you are by advertising and instore promotions and what wine you prefer with

chicken. Big Brother can make big mistakes If electronic information stored about you is wrong, the consequences can be

serious. If your credit rating - determined by one of three credit reference

agencies - is inaccurate, you can be turned down for loans, mobile phone accounts

or credit cards. It might be wrong because of human or computer error, or because

a fraudster has stolen your identity and run up unpaid debts in your name. In 2003, the Criminal Records Bureau wrongly identified at least 193 job applicants

as having criminal records. Ed Mayo, NCC chief executive, says: "What concerns us is how organisations

can use consumers' information and how individuals can keep control of their

information. Personal data is collected, stored and manipulated more than ever

before and much more than most of us realise. Every time we surf the net or

use a credit card, store card or mobile phone, we give away information about

ourselves. We are living in a surveillance society, our data protection laws

aren't up to the job, and the public seems worryingly unconcerned about the

risks.'' Is the Data Protection Act protecting us? The Data Protection Act is supposed to stop companies holding unfair, inaccurate,

excessive and irrelevant information. It gives people the right to release information

to individuals on demand and the right to destroy inaccurate or unfair information

held about them. Companies can only pass on personal details to others with

the consent of the individual. "Research consistently shows that many companies fail to comply with data

protection legislation - often unaware of their legal responsibilities,"

says Mayo. But Caroline Roberts of the Direct Marketing Association, which represents

900 companies, says the personal information economy is in the interest of consumers,

not just marketers. The DMA runs the Telephone and Mail Preference Services,

which allow people to opt out of direct mail and unwanted phone calls from salesmen.

About two million people use the mail opt-out, while more than eight million

have signed up to stop nuisance phone calls. "The thing about direct marketing is that it is using data that people

have given freely with informed consent," she says. "You wouldn't

be on a list unless you'd given consent. From the consumer point of view, it

is sinister if they had no knowledge or no means of finding out about the information

or no means of getting it removed. Where it's not sinister is when it is giving

people choice. There are safeguards and there are ways you can stop it." david.derbyshire@telegraph.co.uk Register with the Preference Services The Telephone Preference Service will stop sales people ringing you at home.

Register at www.tpsonline.org.uk or call 0845 070 0707 (020 7291 3320). The

Mail Preference Service will stop 95 per cent of junk mail. Register at www.mpsonline.org.uk,

call 0845 703 4599 (or 020 7291 3310). Tick opt-out boxes Whenever you provide your name, address and other personal information, the

data may be passed on to direct marketing lists. Remember to tick the box in

the small print asking if you want to opt out of marketing. When you receive

an electoral roll form from your local council, tick the option to remove your

details from the version sold on to companies. Use the Data Protection Act The DPA gives you the right to find out what information is held about you,

correct wrong data and ask a company not to pass on information. Write to the

organisation you believe holds data. In your letter ask: "Please send me

the information which I am entitled to under Section 7(1) of the Data Protection

Act 1998." You will usually have to pay a fee of not more than £10. Check your credit file annually There are three main credit reference agencies: Equifax (Credit File Advice

Centre, PO Box 1140, Bradford, BD1 5US; www.equifax.co.uk); Call Credit (Consumer

Services Team, PO Box 491, Leeds, LS3 1WZ; www.callcredit.plc.uk); Experian

(Consumer Help Service, PO Box 8000, NG80 7WF; www.uk.experian.com). You should

send a fee of £2, your full name and addresses where you have lived over

the last six years and any other names you have been known by. Companies also

offer an instant online credit check, but that costs more. Useful contacts Direct Marketing Association: www.dma.org.uk 020 7291 3300; DMA House, 70 Margaret

Street, London, W1W 8SS Consumers Council: 20 Grosvenor Gardens, London SW1W 0DH, www.ncc.org.uk The Glass Consumer: Life in a Surveillance Society, edited by Dr Suzanne Lace

(the Policy Press, £12.99), is available from the National Consumer Council.

See www.glassconsumer.com

How to keep tabs on 'little brother'