Entered into the database on Sunday, June 25th, 2006 @ 18:00:57 MST

The U.S. economy manages to follow the law and label every electronic

gadget and stitch of clothing with where it comes from. Manufacturers likewise

have no trouble putting a required nutrition list on food packages. But telling

where food originates is called too daunting, and whether it was made by means

unknown in nature is judged irrelevant. The rest of the developed world doesn't see it so, and apparently isn't as

beholden to agribusiness interests as is our government. Americans deserve better.

Congress supported the right of consumers to know where their food comes from

and included a country-of-origin label requirement back in the 2002 farm bill.

But the Agriculture Department opposed this, favoring a voluntary program,

and its economists warned that implementation would cost $1.9 billion. University of Florida researchers, on the other hand, estimated the price would

be 90 percent below that claim and cost consumers less than one-tenth of a cent

per pound of food. The government then quietly lowered its estimate by two-thirds. But the political

damage was done. Congress postponed implementation. Meanwhile, the nation's four biggest meat packers, which process more than

80 percent of the beef in this country, are quite happy. Without the label requirement,

they can continue to import cheaper foreign beef to leverage down the price

of American cattle. This imported beef gets an Agriculture Department inspection

label when processed here, and is sold to unsuspecting consumers, who assume

it is expensive American beef. Also keeping consumers in the dark, the Food and Drug Administration refuses

to require labels on food whose production involves genetic modification. In 1994, the agency approved commercial use of a genetically engineered bovine

growth hormone to increase milk production, and said that no label was needed.

Canada looked at the same test data from the manufacturer, Monsanto, and banned

the hormone. So did the European Union, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and other

industrialized countries. There is concern that the hormone raises human cancer

risk. And because cows on the production stimulant are more prone to udder infection,

more antibiotics are used. Overuse of antibiotics undermines our pharmaceutical

arsenal by encouraging antibiotic resistance in bacteria. The Agriculture Department reported in 2002 that 2 million of America's 9.2

million dairy cows received the hormone, and that larger dairies use it far

more than farms with fewer than 100 cows. Given the industry's mixing of milk

from many farms, most U.S. dairy products have milk from injected cows. The FDA ruled in 1992 that genetically modified food did not differ from other

foods in any meaningful way. But there was considerable debate within the FDA

over the differences between foods with and without genetic modification. A

lawsuit filed by the Alliance for Bio-Integrity prompted the agency to release

documents that highlighted the concerns some agency scientists had about biotech

foods. But under this country's present voluntary system, they remain unlabeled. Polls

show that demand for this kind of food is low, and a large majority wants labeling.

That could spell market failure, so biotechnology companies and agribusiness

giants are opposed. Without any labeling and separating of genetically modified ingredients, many

overseas buyers have rejected corn, soy, canola, and cotton from the United

States and Canada. In this country, large natural-food supermarket chains have

announced that they will use no genetically modified foods in store brands.

But most processed food in this country contains soy, corn, or both in some

form, and 80 percent of soy and 38 percent of corn commercially grown in the

United States is genetically altered. In a free and open market, transparency is necessary for consumers to know

what they are getting. Scientists and nations around the world recognize this.

But where and how Americans' food is raised too often remains hidden. We should

enjoy the basic right to know. Paul D. Johnson, an organic-market gardener and a family-farm

legislative advocate for several churches in Kansas, is a member of the

Land Institute's Prairie Writers Circle,

in Salina, Kansas. _____________________________ Test Tube Meat Nears Dinner Table By Lakshmi Sandhana What if the next burger you ate was created in a warm, nutrient-enriched soup

swirling within a bioreactor? Edible, lab-grown ground chuck that smells and tastes just like the real thing

might take a place next to Quorn

at supermarkets in just a few years, thanks to some determined meat researchers.

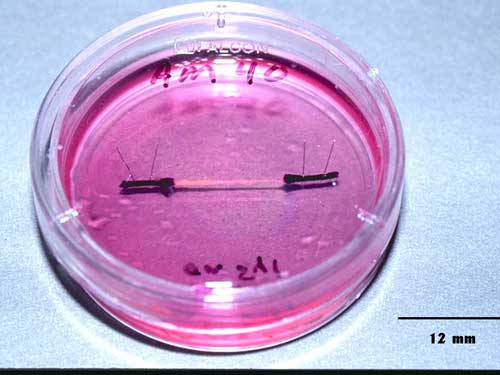

Scientists routinely grow small quantities of muscle cells in petri dishes for

experiments, but now for the first time a concentrated effort is under way to

mass-produce meat in this manner. Henk Haagsman, a professor of meat sciences at Utrecht University, and his

Dutch colleagues are working on growing artificial pork meat out of pig stem

cells. They hope to grow a form of minced meat suitable for burgers, sausages

and pizza toppings within the next few years. Currently involved in identifying the type of stem cells that will multiply

the most to create larger quantities of meat within a bioreactor, the team hopes

to have concrete results by 2009. The 2 million euro ($2.5 million) Dutch-government-funded

project began in April 2005. The work is one arm of a worldwide research effort

focused on growing meat from cell cultures on an industrial scale. "All of the technology exists today to make ground meat products in vitro,"

says Paul Kosnik,

vice president of engineering at Tissue Genesis in Hawaii. Kosnik is growing

scaffold-free, self-assembled muscle. "We believe the goal of a processed

meat product is attainable in the next five years if funding is available and

the R&D is pursued aggressively." A single cell could theoretically produce enough meat to feed the world's population

for a year. But the challenge lies in figuring out how to grow it on a large

scale. Jason Matheny, a University

of Maryland doctoral student and a director of New

Harvest, a nonprofit organization that funds research on in vitro meat,

believes the easiest way to create edible tissue is to grow "meat sheets,"

which are layers of animal muscle and fat cells stretched out over large flat

sheets made of either edible or removable material. The meat can then be ground

up or stacked or rolled to get a thicker cut. "You'd need a bunch of industrial-size bioreactors," says Matheny.

"One to produce the growth media, one to produce cells, and one that produces

the meat sheets. The whole operation could be under one roof." The advantage, he says, is you avoid the inefficiencies and bottlenecks of

conventional meat production. No more feed grain production and processing,

breeders, hatcheries, grow-out, slaughter or processing facilities. "To produce the meat we eat now, 75 (percent) to 95 percent of what we

feed an animal is lost because of metabolism and inedible structures like skeleton

or neurological tissue," says Matheny. "With cultured meat, there's

no body to support; you're only building the meat that eventually gets eaten." The sheets would be less than 1 mm thick and take a few weeks to grow. But

the real issue is the expense. If cultivated with nutrient solutions that are

currently used for biomedical applications, the cost of producing one pound

of in vitro meat runs anywhere from $1,000 to $10,000. Matheny believes in vitro meat can compete with conventional meat by using

nutrients from plant or fungal sources, which could bring the cost down to about

$1 per pound. If successful, artificially grown meat could be tailored to be far healthier

than any type of farm-grown meat. It's possible to stuff if full of heart-friendly

omega-3 fatty acids, adjust the protein or texture to suit individual taste

preferences and screen it for food-borne diseases. But will it really catch on? The Food and Drug Administration has already barred

food products involving cloned animals from the market until their safety has

been tested. There's also the yuck factor. "Cultured meat isn't natural, but neither is yogurt," says Matheny.

"And neither, for that matter, is most of the meat we eat. Cramming 10,000

chickens in a metal shed and dosing them full of antibiotics isn't natural.

I view cultured meat like hydroponic vegetables. The end product is the same,

but the process used to make it is different. Consumers accept hydroponic vegetables.

Would they accept hydroponic meat?" Taste is another unknown variable. Real meat is more than just cells; it has

blood vessels, connective tissue, fat, etc. To get a similar arrangement of

cells, lab-grown meat will have to be exercised and stretched the way a real

live animal's flesh would. Kosnik is working on a way to create muscle grown without scaffolds by culturing

the right combination of cells in a 3-D environment with mechanical anchors

so that the cells develop into long fibers similar to real muscle. The technology to grow a juicy steak, however, is still a decade or so away.

No one has yet figured out how to grow blood vessels within tissue. "In the meantime, we can use existing technologies to satisfy the demand

for ground meat, which is about half of the meat we eat (and a $127 billion

global market)," says Matheny. ___________________________ Read from Looking Glass News Genetically

Engineered Crops May Produce Herbicide Inside Our Intestines Monsanto

develops "Genetically Modified Pig": The patenting of livestock GM:

New study shows unborn babies could be harmed

Wired.com