Entered into the database on Wednesday, December 28th, 2005 @ 21:15:53 MST

Abidjan, Ivory Coast -- The U.S. government will spend $500 million

over five years on an expanded program to secure a vast new front in its global

war on terrorism -- the Sahara Desert. But critics say the region is not a terrorist zone, as some senior U.S. military

officers assert, and they warn that a heavy-handed military and social campaign

that reinforces authoritarian regimes in North and West Africa could fuel radicalism

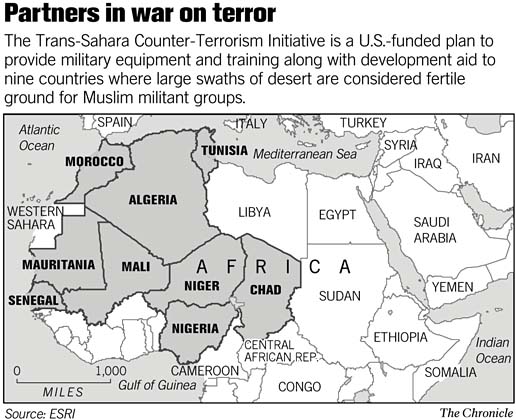

where it scarcely exists. The Trans-Sahara Counter-Terrorism Initiative began operations in June to provide

military expertise, equipment and development aid to nine Saharan countries

where lawless swaths of desert are considered fertile ground for militant Muslim

groups involved in smuggling and combat training. "It's the Wild West all over again," said Maj. Holly Silkman, a public

affairs officer at U.S. Special Operations Command Europe, which presides over

U.S. security and peacekeeping operations in Europe, former Soviet bloc countries

and most of Africa. Algeria, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Morocco,

Nigeria and Tunisia take part in the initiative. During the first phase of the program, dubbed Operation Flintlock, 700 U.S.

Special Forces troops and 2,100 soldiers from nine North and West African nations

led 3,000 ill-equipped Saharan troops in tactical exercises designed to better

coordinate security along porous borders and beef up patrols in ungoverned territories.

The trans-Sahara initiative aims to defeat ideological entrepreneurs trying

to gain a foothold by reaching out to the "disaffected, disenfranchised,

or just misinformed and disillusioned," Silkman said. The head of Special Operations Command Europe, Maj. Gen. Thomas Csrnko, said

he was concerned that the al Qaeda terrorist network is assessing African groups

for "franchising opportunities," notably the Salafist Group for Call

and Combat (known as GSPC for its initials in French), which is on the U.S.

State Department's list of foreign terrorist organizations. The Algeria-based Salafist Group, which reportedly aims to topple the Algerian

government and create an Islamic state, is estimated to have about 300 fighters.

It was accused of kidnapping European tourists in 2003 and has taken responsibility

for a spate of attacks in the Sahara this year. Thirteen Algerian soldiers were killed and six were wounded when a Salafist

bomb exploded under a truck convoy on June 8. Twelve troops died May 15 in an

ambush 300 miles east of Algiers. Fifteen Mauritanian soldiers were killed and

17 were wounded in a June 4 raid on a remote military outpost. Some victims

reportedly had their throats slit. The Salafist Group said the offensive was a "message that implies that

our activity is not restricted to fighting the internal enemy but enemies of

the religion wherever they are." European Command officials say there is recent evidence that 25 percent of

suicide bombers in Iraq are Saharan Africans, and they suspect that "fighters

are being trained in Iraq and then transiting back to Africa with the ability

to teach techniques" to recruits there. Terrorist attacks such as the March

11, 2004, Madrid train bombings that killed 191 people have been linked to North

African militants. The U.S. military and the State Department, which officially leads the program,

are counting on an annual budget of at least $100 million for the trans-Sahara

initiative from 2007 until 2011. This represents a big increase from the Pan-Sahel

Initiative, a $7 million forerunner that was initiated in 2002 in what Theresa

Whelan, U.S. deputy assistant secretary of defense for African affairs, called

"just a drop in the bucket" compared with the region's needs. Some observers say terrorism in the Sahara is little more than a mirage and

that a higher-profile U.S. involvement could destabilize the region. "If anything, the (initiative) ... will generate terrorism, by which I

mean resistance to the overall U.S. presence and strategy," said Jeremy

Keenan, a Sahara specialist at the University of East Anglia in Britain. A report by the International Crisis Group, a Brussels-based think tank, said

that although the Sahara is "not a terrorist hotbed," repressive governments

in the region are taking advantage of the Bush administration's "war on

terror" to tap U.S. largesse and deny civil freedoms. The report said the government of Mauritanian President Maaoya Sid'Ahmed Ould

Taya -- a U.S. ally in West Africa who was deposed Aug. 3 in a bloodless coup

-- used the threat of terrorism to justify human rights abuses. Taya jailed

and harassed dozens of opposition politicians, charging that they were connected

to the Salafist Group. This has made the trans-Sahara initiative unpopular among

some Mauritanians, said Princeton Lyman, director of African policy studies

at the Council on Foreign Relations. In June, hundreds of Mauritanians filled

the streets of Nouakchott, the capital, to protest the start of the initiative.

Keenan said U.S. intelligence about the Saharan region is sparse. In fact,

the questions about intelligence extend to the actions and very existence of

at-large Salafist second-in-command Abderrazek Lamari, alias "El Para,"

who is thought to be the mastermind of the 2003 hostage kidnapping. Keenan said

contradictory Algerian intelligence reports and eyewitness testimonies suggest

collusion between agents of Algeria's military intelligence services and the

Salafist Group. The State Department declined to comment on the matter. Aside from the 2003 kidnapping issue, U.S. and Algerian authorities have failed

to present "indisputable verification of a single act of alleged terrorism

in the Sahara," Keenan said. "Without the GSPC, the U.S. has no legitimacy

for its presence in the region," he said, noting that a growing American

strategic dependence on African oil has led the United States to bolster its

presence in the region. "African oil is of national strategic interest to us, and it will

increase and become more important as we go forward,'' Walter Kansteiner, former

assistant secretary of state for African affairs, said as early as 2002. A report

by the National Energy Policy Development Group anticipates that by 2015, West

Africa will provide a quarter of the oil imported by the United States. Nigeria is the fifth-largest source of U.S. oil imports. Algeria has

at least 9 billion barrels of reserves, and Mauritania has begun offshore pumping

that could make it Africa's No. 4 oil supplier by 2007. Silkman, however, said cultivating security, not oil resources, is the prime

objective of the trans-Sahara initiative. She said it is vital that other members

of the international community get involved -- especially France, which has

a broad military-diplomatic network in the region. She also said critics have overlooked the socioeconomic and developmental pillars

of the initiative, which provide $70 million a year for projects to promote

democracy and stimulate economic growth. "Reducing the threat is not as much about taking direct action as it is

in eliminating conditions that allow terrorism to flourish," she said.

As one special operations officer at the European Command involved in the initiative

put it: "It's not as much about killing alligators as it is about draining

the swamp."